BKMT READING GUIDES

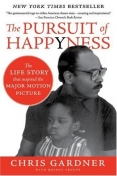

The Pursuit of Happyness

by Chris Gardner

Paperback : 320 pages

5 clubs reading this now

4 members have read this book

The astounding yet true rags-to-riches saga of a homeless father who raised and cared for his son on the mean streets of San Francisco and went on to become a crown prince of Wall Street

At the age of twenty, Milwaukee native Chris Gardner, just out of the Navy, arrived in San Francisco to ...

Introduction

The astounding yet true rags-to-riches saga of a homeless father who raised and cared for his son on the mean streets of San Francisco and went on to become a crown prince of Wall Street

At the age of twenty, Milwaukee native Chris Gardner, just out of the Navy, arrived in San Francisco to pursue a promising career in medicine. Considered a prodigy in scientific research, he surprised everyone and himself by setting his sights on the competitive world of high finance. Yet no sooner had he landed an entry-level position at a prestigious firm than Gardner found himself caught in a web of incredibly challenging circumstances that left him as part of the city's working homeless and with a toddler son. Motivated by the promise he made to himself as a fatherless child to never abandon his own children, the two spent almost a year moving among shelters, "HO-tels," soup lines, and even sleeping in the public restroom of a subway station.

Never giving in to despair, Gardner made an astonishing transformation from being part of the city's invisible poor to being a powerful player in its financial district.

More than a memoir of Gardner's financial success, this is the story of a man who breaks his own family's cycle of men abandoning their children. Mythic, triumphant, and unstintingly honest, The Pursuit of Happyness conjures heroes like Horatio Alger and Antwone Fisher, and appeals to the very essence of the American Dream.

Excerpt

From The Publisher: Chapter One Candy In my memory's sketch of early childhood, drawn by an artist of the impressionist school, there is one image that stands out above the rest—which when called forth is preceded by the mouth-watering aroma of pancake syrup warming in a skillet and the crackling, bubbling sounds of the syrup transforming magically into homemade pull candy. Then she comes into view, the real, real pretty woman who stands at the stove, making this magic just for me. Or at least, that's how it feels to a boy of three years old. There is another wonderful smell that accompanies her presence as she turns, smiling right in my direction, as she steps closer to where I stand in the middle of the kitchen—waiting eagerly next to my sister, seven-year-old Ophelia, and two of the other children, Rufus and Pookie, who live in this house. As she slips the cooling candy off the wooden spoon, pulling and breaking it into pieces that she brings and places in my outstretched hand, as she watches me happily gobbling up the tasty sweetness, her wonderful fragrance is there again. Not perfume or anything floral or spicy—it's just a clean, warm, good smell that wraps around me like a Superman cape, making me feel strong, special, and loved—even if I don't have words for those concepts yet. Though I don't know who she is, I sense a familiarity about her, not only because she has come before and made candy in this same fashion, but also because of how she looks at me—like she's talking to me from her eyes, saying, You remember me, don't you? At this point in childhood, and for most of the first five years of my life, the map of my world was broken strictly into two territories—the familiar and the unknown. The happy, safe zone of the familiar was very small, often a shifting dot on the map, while the unknown was vast, terrifying, and constant. What I did know by the age of three or four was that Ophelia was my older sister and best friend, and also that we were treated with kindness by Mr. and Mrs. Robinson, the adults whose house we lived in. What I didn't know was that the Robinsons' house was a foster home, or what that meant. Our situation—where our real parents were and why we didn't live with them, or why we sometimes did live with uncles and aunts and cousins—was as mysterious as the situations of the other foster children living at the Robinsons'. What mattered most was that I had a sister who looked out for me, and I had Rufus and Pookie and the other boys to follow outside for fun and mischief. All that was familiar, the backyard and the rest of the block, was safe turf where we could run and play games like tag, kick-the-can, and hide-and-seek, even after dark. That is, except, for the house two doors down from the Robinsons. Every time we passed it I had to almost look the other way, just knowing the old white woman who lived there might suddenly appear and put an evil curse on me—because, according to Ophelia and everyone else in the neighborhood, the old woman was a witch. When Ophelia and I passed by the house together once and I confessed that I was scared of the witch, my sister said, "I ain't scared," and to prove it she walked right into the front yard and grabbed a handful of cherries off the woman's cherry tree. Ophelia ate those cherries with a smile. But within the week I was in the Robinsons' house when here came Ophelia, racing up the steps and stumbling inside, panting and holding her seven-year-old chest, describing how the witch had caught her stealing cherries and grabbed her arm, cackling, "I'm gonna get you!" Scared to death as she was now, Ophelia soon decided that since she had escaped an untimely death once, she might as well go back to stealing cherries. Even so, she made me promise to avoid the strange woman's house. "Now, remember," Ophelia warned, "when you walk by, if you see her on the porch, don't you look at her and never say nuthin' to her, even if she calls you by name." I didn't have to promise because I knew that nothing and no one could ever make me do that. But I was still haunted by nightmares so real that I could have sworn I actually snuck into her house and found myself in the middle of a dark, creepy room where I was surrounded by an army of cats, rearing up on their back legs, baring their claws and fangs. The nightmares were so intense that for the longest time I had an irrational fear and dislike of cats. At the same time, I was not entirely convinced that this old woman was in fact a witch. Maybe she was just different. Since I'd never seen any white people other than her, I figured they might all be like that. Then again, because my big sister was my only resource for explaining all that was unknown, I believed her and accepted her explanations. But as I pieced together fragments of information about our family over the years, mainly from Ophelia and also from some of our uncles and aunts, I found the answers much harder to grasp. How the real pretty woman who came to make the candy fit into the puzzle, I was never told, but something old and wise inside me knew that she was important. Maybe it was how she seemed to pay special attention to me, even though she was just as nice to Ophelia and the other kids, or maybe it was how she and I seemed to have a secret way of talking without words. In our unspoken conversation, I understood her to be saying that seeing me happy made her even happier, and so . . . The foregoing is excerpted from The Pursuit of Happyness by Chris Gardner. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022Discussion Questions

No discussion questions at this time.Weblinks

| » |

Official Chris Gardner Website

|

| » |

Information On The Film

|

| » |

An Interview With Chris Gardner

|

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more