BKMT READING GUIDES

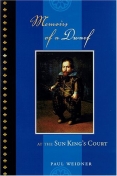

Memoirs of a Dwarf: At the Sun King's Court

by Paul Weidner

Hardcover : 346 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Set in the over-scaled, decadent Versailles of Louis XIV, Memoirs of a Dwarf is the story of Hugues, an impoverished dwarf who maneuvers his way up into the very highest of court circles by clandestinely serving the needs of a mob of unscrupulous gamblers, of a priest notorious for saying black Masses at midnight, and—from under the gaming tables—of a number of sex-starved society women, including Louis's mistress. Along the way, Hugues finally discovers the truth of his own identity, a revelation which is a political bombshell and which subjects him to a grisly turn.

The story combines historical events and characters—Louis, his mistresses, his outrageous brother Philippe, and many other baroque personalities—with fictitious ones. Hugues’s tale reaches its climax during the famous affaire des poisons, the sexual and political scandal that thundered through the royal court and threatened wholesale destruction.

Excerpt

Chapter Six I report the following as abruptly as it happened. Madame Scarron’s entire household, almost overnight, moved out of the estate at Vaugirard – the mistress, the two children, the various maids, nurses, footmen, and myself – but not the surly grooms – to the royal town of St. Germain-en-Laye, where stands one of my lord Louis’s most principal residences, a chateau built in 1539 by François I. And reader, to my great wonderment, it was not only to the royal town that we moved but into that most principal – and indeed most royal – chateau itself! And when eventually I managed to ferret out the fact – for I was informed of nothing in a straightforward manner but had always to ferret out information – the information, I say, that this same chateau was where the two divinities themselves resided and that we should all now be living under the one same roof with them, my heart fairly leapt for joy, not only at my own good fortune but at that of the two royal bastards, who would now be at least within howling distance of their own dearest mother; and I rejoiced yet again at the pleasure that such proximity would furnish her with. Yet such are those devilish first impressions that they often turn out to be misleading, and I ought truly to have realized that Mme Scarron, as the children’s official guardian, would, even in these new circumstances, allow them as little access to their parents as she could possibly contrive: for that lady, true to her ways, assumed a new degree of hauteur in this entrée to the royal court, and her possessiveness toward Louis-Auguste and Louis-César likewise assumed new heights, for was this not that further step up the social ladder which she had sought – indeed several further steps – and had those same two boys not been the very means to it? And furthermore, since the condition under which the boys lived, I mean that of bastardy, imposed a less than public acknowledgement of them by their mother, Madame Scarron held sway, and my hopes for the divinity’s new happiness were dashed. As for Mme Scarron’s followers, I mean her weekly soirée set, they were now invited every Tuesday evening to her private apartment in the chateau, and it seemed not to occur to them that their excellent new fortunes were attributable directly to Scarron herself, as hers were directly to the two infants; which is to say that their fortunes were vicarious at best and likely to be tenuous. For all, even the few commoners amongst them, conducted themselves in these more sumptuous surroundings like newly beplumed peacocks, with all the same vanity and all the same cruelty which those vile beasts are wont to exhibit; and they began vying more than ever with one another with lavish displays of their feathers and with kicking sand at each other and with biting at each other’s throats. On the other hand, Louis-Auguste, Louis-César as well as Louise-Françoise, their sister, a newcomer who had arrived but lately on the scene, comported themselves in their recently enhanced living quarters with none of the arrogance of Mme Scarron and her entourage. To my great surprise, all three children, with a combined age of five, seemed even quite oblivious to the move, Louis-Auguste having now become so preoccupied with his misshapen limb and so discontent at the misappropriation of his mother as not to give two figs for where he lived, but then he was only three years old and artless; and Louis-César, at the age of two, and Louise-Françoise, an infant, quite uncomprehending of anything. There would be ample time for all of them to learn the proper ways of arrogance. As for myself, it would be natural for you to assume that upon removal from a window seat in the topmost floor of a somewhat country house to the royal residence at St. Germain-en-Laye, famous as the birthplace of the kings of France, an eleven (or twelve)-year-old would have instantly become quite swell-headed. But by and large I did not. Yet I will not conceal from you – for truth is to be served – my awareness of my good fortune in this removal. Here again had fallen to me one of those boons, not of my own doing, but of which, even so, I might take excellent advantage; and I think you must agree with me that a dwarf employed at the royal court of France had not a little advanced beyond that same creature toiling away in a pitiful village outside Paris, even if his new assignments continued to be in kitchens, pump rooms, and chimney places; and as well, that his opportunities for advancement were much enhanced In all honesty, however, this report about myself must admit of one exception, an event from which I suffered a harsh lesson and learned exceeding much. And it was this: I was most grateful that Mme Amélie continued on at St. Germain in her service to Mme Scarron and her teats in service to the Louis, for I had become right fond of the woman and she, of all the people in that set, had always treated with me fairly and honestly; and I would even dare to say that she returned some small affection for me but that I do not like to presume. Several months after our arrival at the chateau I saw one morning that madame was wearing a brand new outfit: it was dress appropriate to her servile station, both modest and sober, but yet it impressed me that she had apparently felt some compunction to acknowledge her new and more splendid surroundings and, as it were, to show respect for them in her own attire. She told me that having put aside some money, she had engaged the services of a dressmaker in the town a few weeks earlier, who had only the day previous delivered the finished dress to the chateau. This act inspired in my own mind a sense of obligation to the new surround; and since I too had now been able to put aside some savings from my employment at the card tables, I approached the lady later that day and addressed her: "Mme Amélie," quoth I, "I would be obliged to you if you would direct me to your tailor, whose services I wish to engage." "'Lud, sir," she replied, "and what's got into your noggin now, Monsieur Hugues? Them things you've got on is right suitable, sir, I think; and anyways, no tailor works for nothing, 'specially the ones in this town don't." "Madame, I am aware of that; but I have now some income and am ready to meet the going rate." Mme Amélie was quite surprised at this, for she knew nothing of my evening employment. "So!" said she, laughing the whiles, "and pray, how much have you got there?" "Madame, all told, it comes to one louis d'or and seventy centimes." "Do you say so! Well, you're a right enterprising bugger, ain't you now! But sir: that's nowheres near enough for a tailor's wages. Maybe you could buy some stockings with that louis and a handky with them centimes!" She fell to laughing again at my innocence; but yet when she saw how crestfallen I was at this unhappy news, she chucked me under the chin and said, "Now, now, now; cheer up there! Tell you what, Monsieur Hugues, you go with me to market next time; I know a fellow's got some old clothes for sale – we'll see what he can do for you." Now old clothes were not exactly what I had in mind, reader, for there was nothing old about the display of outfits which I saw all around me, and that included even what the lackeys and grooms wore thereabouts. Yet I saw no way around it, and I thanked Mme Amélie for her kindness. A week later came market day, and we set out. Reader, it was the first time in my life that I had beheld so fine a city as St. Germain-en-Laye! Just across the road from the gates of the chateau stands an imposing church and from it there radiates a bewildering array of streets and byways – I counted as many as six – all lined with magnificent dwellings, some towering as high as four stories. Mme Amélie had to hasten me along, for I gawked unashamedly at the richness of the buildings and at the teeming traffic in all the roads, people of all descriptions coming and going, carts, wagons, sedan-chairs, and carriages, dogs, chickens, and pigs all swarming about hither and thither and crowding into the lanes. At length we arrived at the marketplace, a majestic square in the center of the metropolis lined on all four sides with tall houses – as many as seven or eight on each side – and overrun with a vast open-air market, where truly I believe you must be able to purchase every conceivable article of merchandise in all of Christendom. Madame went about her several errands and I tagging along behind, ignoring the taunts of several dirty street urchins who I think can never have seen a dwarf before in their wretched ignorance, and staring all about me at the wonders of a city most surely in its grandeur befitting that most illustrious of its many inhabitants, I mean our sovereign Highness, King Louis, Fourteenth of that Majestic Name! But finally madame led me to a stall near the very center of the square, where bundles of clothing hung on hooks and lines or lay piled up in boxes and chests and some even on the bare ground. I confess, the sheer quantity of goods was overwhelming – there were doublets and shirts in stacks, heaps of breeches and vests, and stuffed in among them all, collars, shoes, stockings, and hats wherever my eyes fell. "That fellow is an Israelite," madame informed me, pointing to a man with a long dark coat, a wide dark beard and a flat dark hat who was in charge of the stall, "but that is no matter. Look around – it's all secondhand, and some of it ain't too dear." Reader, I began to search about, holding various pieces of clothing up to judge of their size in relation to my own: everything seemed musty and mildewed, not to say patched, shabby, and very well worn. My heart sank: this was not what I wished to spend my hard-earned savings upon. But as luck would have it and after a lengthy and determined if somewhat dusty search, I happened upon a woolen doublet, of a bright purple color, adorned with embroidered gold stitching down the front and along the pockets, and lined in red taffeta; the lining was shredded in places but the doublet itself did not seem overly worn, and the brightness of the colors, I thought, surely belied its age and former usage. Throwing off my own jacket, I slid my arms into the sleeves; quickly I felt the smooth lining against my back and the firm weight of the coat upon my shoulders; the colors dazzled my eyes; the embroidery felt rich as I ran my fingers over it; and even the fragrance of the material was exquisite! "This one," I said, turning to the Israelite. But before he could reply: "No, no, no, Monsieur Hugues!" exclaimed Mme Amélie. "Too gaudy by half, sir! Why, you look like some kind of a carnival there! And then it's way too long – look back there where it hits your leg." I could feel the hem against the middle of my calf, it is true; but when the Israelite hastened to point out that it was quite the fashion that season to wear one's doublet somewhat long, my mind was again resolved upon it. Next he slipped a baldric over my head and fastened it to the right shoulder of the doublet: the sash fell across my chest and on down to my left knee. It was sumptuous, all covered in gold braid and with a fine big knot at the bottom and below, a tuft of shiny fringe. "'Lud, sir!" cried madame, speaking I knew not at first whether to me or the merchant. “Why, now you're making a downright spectacle of yourself, so you are! And no bones about it!" But reader, I knew that the doublet and baldric were magnificent and was certain that I looked magnificent in them, and I glanced back at madame's sober dress and decided that in fact, as kindly as she was and as generous and thoughtful, the woman clearly had no taste. I informed the proprietor that I had exactly one louis d'or and seventy centimes to spend and that I would not offer him a sou more; whereupon he said that the cost of the two pieces was in fact some forty centimes above that sum, but that because the clothes became me so perfectly and because he was eager to oblige so exceptional a lad as I, he would consent to settle at the lower figure. "Excellent!" I exclaimed, slipping off the clothes so that he could fold them into a bundle. I would simply forego buying breeches and a shirt for the present. Reader, when I reached into my pocket and withdrew my one louis d'or and my seventy centimes and handed them over to that most worthy gentleman and in return clasped the bundle into my own two arms, my heart leapt with the sheer joy of the purchase, and my face broke into a flush and my head was fairly spinning! And I thought how truly estimable these Israelites can be! and what excellent good bargains the clever buyer can strike with them! and how invaluable their commerce is to our society! That very evening, reader, as it befell, was a Tuesday, and my services were called upon as usual to distribute flan. Carefully I unfolded my new doublet, noticing as I did that there were some stains under the arms which I had overlooked in the hustle and bustle of the marketplace; but after some study I was certain that they would hardly show. I put the doublet on. I adjusted my shirt and collar. Next I attached the baldric. The fringe at the bottom, I noticed, dragged a bit along the floor; but less so if I held my right shoulder upward. I smoothed my hair down with a bit of spit and fought a while with my cowlick. I brushed off my shoes. I set out to collect the flan. My heart was thumping. Gasps of surprise from the maids and butlers greeted me as I entered the kitchen building. It was only natural, thought I to myself, that these servants should be impressed by my change in appearance, to say nothing of the magnificence of my fashionably long doublet and baldric. The several giggles and the one or two guffaws that followed that first reaction came from the lower orders, I noticed, scullery maids and such, who could not be expected to have any sense of these matters. Taking up the tray of flan, I sailed away, back over into the chateau, up the stairs, and down the hallway toward the salon where Mme Scarron’s guests were gathered. I felt my heart thumping faster as I approached, my throat was dry, and once or twice I caught the end of the baldric under my left foot. Yet I pressed onward, reached the doorway, gripped the tray anew, swallowed hard, thrust my right shoulder upward, and entered the room. Reader, to my amazement, I met, as I had met some four years earlier that first Tuesday evening in the drawing room at Vaugirard, an instant explosion of glee: the first people who saw me cross the threshold fell into gales of mirth, attracting those nearby to turn and look, whereupon they too began hooting with laughter and attracting still others, until in very short order, the entire room was shaking with hilarity, everyone pointing their fingers at me, holding their sides or slapping their hands on the tables, their eyes streaming, their wigs slipping awry, and the cards flying up from out of their hands. "Monsieur Hugues! Monsieur Hugues!" they shouted through their laughter. “What a fine doublet you have on, sir, ha ha ha! So bright and so purple! And the trim, dear God, look at the trim! And see! see how majestically the fringe simply trails along behind on the floor! Ha ha ha!" and such-like cruel and sarcastical remarks. By now the thumping of my heart had become a raucous pounding, my face was flushed as red as the shredded lining of my doublet, and I found that I could scarcely see for the stinging wall of tears that filled my eyes. In fact, I could not see, not well enough to go about my task, and having served one table with flan, as I moved to the second, I tripped on the fringe from the baldric and fell, and the cups of flan went crashing to the floor and sliding this way and that all about the room. Whereupon yet another wave of mirth erupted throughout the company. Reader, once I had fought my way through the confusion of my tears and of the crowded salon and had recovered all the scattered cups of flan, I flew back to the kitchen and deposited the custard as quickly as I could; but not so quickly, alas, that I was not compelled to endure yet more uproarious laughter, and now from the entire kitchen staff, who saw clearly my humiliation and enjoyed freely and to the full my awful distress. Next, I raced to the brush closet where I kept my things and instantly changed back to my old clothes. And to my only clothes, I must add, for I vowed never again to don that doublet and baldric; and later that night I crept back to the brush closet, gathered up my new purchases, carried them down to the riverbank, and threw them in. I believe, reader, that I may honestly state that not one other time have I presumed to put on airs in such a shameful fashion and that I learned a bitter lesson about the ways of seeking to better oneself in this world: for we must be aware of our proper station in society and may take measures to advance ourselves only in ways that are appropriate to that station. And in my eagerness or innocence or arrogance or I know not what youthful flaw, I had not heeded that unshakable principle of life. Indeed, had I ever again even been tempted to assume airs that were not becoming, I was constantly reminded of my proper humility by an unavoidable aspect of life at the court of St. Germain, to wit, the presence of His Majesty’s hunting dogs, being, as I was, roughly their size and operating – but less roughly than they – on their level. These creatures, which were great favorites of the king’s, had the run of the palace despite an inordinate lack of house training – and they dropped great turds all about the place, which was fine and well for those who lived several more feet above grade than I. The beasts took full advantage of an ingenious system which the king had had installed, whereby hinged panels were fitted into the lower parts of all the doors, designed to align unobtrusively with the existing moldings, so that by pushing through the panels, the dogs could make their way from any room in the place to any other room. Since they tended to move about in tight packs, it was not an uncommon sight for the lower part of an imposing and stately door suddenly to burst open, as though it had flung up its skirts, and release a galloping, slobbering, yelping explosion of hounds. Need I point out that I did not run with these hounds, reader; though more often than not I did try to run well ahead of them, but with varying results. The royal dogs were kept on the verge of starvation; as such, by sheer neglect, the Godforsaken creatures at the monastery had been, those dogs which had at times tried to make a light supper of me until I learned to fend them off with smoldering coals from the grates. But the dogs of St. Germain were kept hungry by design, for they were hunters, and a somewhat edgy condition for them was desirable; and it was just that degree of edge, coupled with their natural viciousness and exacerbated by the additional irritation that they themselves were constantly being munched upon by similarly hungry fleas that provoked the animals to pursue, wherever they could, smaller game such as foxes, hares, pheasants, and, in my case, dwarves. (By contrast, I now looked upon Mme de St. Estève’s overfed hounds as positively companionable.) And so, preferring not to be cornered and shredded asunder, I found that it behooved me to make use myself of their own device, to wit, the hinged door panels, which furnished me a greater freedom of movement during a chase; though clearly they too leapt through the panels as nimbly as I. But to my advantage was this fact: the irregularly shaped rooms at St. Germain (I speak now of the old chateau) and the paucity of natural light in them had led to the installation of a number of mirrors about the place. The dogs, being too stupid to understand the reflective properties of mirrors, could often be tricked into chasing a mere image of myself on one side of a room whilst I, corporeally on the opposite, stole my way to safety through a hinged panel, the dogs then setting up a howl at the mysterious disappearance of their quarry; and in frustration and revenge and I know not what other canine emotions, they would then make copious water upon whatever mirror had consumed their prey, or perform other, more hideous acts in the area. But this ruse was not always successful and I fought for my very life with one or more of them on many an occasion, providing idlers nearby with something of an impromptu sporting event: “Twenty écus on the beast!” I might hear as I was wrestling with a foxhound. “On which beast?” “Why, upon the dwarf, of course!” “No, no, I raise you: thirty-five on the hound!” and so on. That carefree gambler could not have known, I think, the pain he caused me by referring to me as a beast: all of this is by way of revealing that any elevation in status which I might have conceived for myself in the removal from the commonplace world of Vaugirard to the wealth and public animation of the chateau at St. Germain-en-Laye was well tempered by the constant humiliations which I endured, as you have now seen. That wealth and public animation which I now discovered about me were indeed breathtaking, though I witnessed not even the half of it: every day there were ambassadors and delegations streaming through the halls and from every imaginable land: here came Turks, giants top-heavy with bejeweled turbans, noisy, brawling, spitting, and with long hooked noses and flaring nostrils, swarthy and hairy, smelling of tallow, with droves of red monkeys in tow, leashed on silver chains, chattering and spitting as much as ever their masters did; or squinting Chinese, borne aloft on lacquered palanquins, holding silken handkerchiefs up to their yellow noses against the odors which emanated, or so they maintained, from the flesh of Europeans, whilst the towering umbrellas paraded above their heads kept crashing into the doorways; or half-naked Indians bedizened in feathers and gold, from the opposite side of the globe, from the territories of the Guyane, from Peru, and the farthest Antilles. (It is there where exist those creatures which I have mentioned earlier which are huge and have heads and arms and hands, legs and feet, all like men, but no bodies whatsoever: and they are the anthropophagi; they eat human flesh, and although that human flesh then becomes their own flesh, yet they themselves are no more human than before; and this information about them is true, for I have made a study of it.) Here I found, of an evening, not one drawing room of gaming tables but an entire series of such rooms, some in the north galleries which formed the apartment where lived King Louis Himself with His son, a somewhat bulbous youth about a year my junior, himself a Louis, the heir apparent and known as Monseigneur the Dauphin; and in the east galleries, several more intimate rooms where the queen’s apartment was located. (For, reader, there was indeed, I soon discovered, a queen of France, a childish and gluttonous middle-aged Spanish woman, Marie-Thérèse, the so-called Infanta, whose French was execrable and whose personal share in the divinity that I had come to associate with royalty was nowhere in evidence; for whether it was due to the considerable weight which she had accumulated over the years or to a certain cultural deprivation she had suffered in her youth, she was given to a great deal of noisy farting; and hawking, sneezing, and the prodigious blowing of her nose and various other exhalations; all of which, according to the physicians, could easily have been cured with a few good bleedings; but she would have none of it; and I believe, in the end, that those respiratory and digestive activities might have been an attempt by her to have someone pay her some heed, for she was much overlooked.) At the gaming tables, almost every evening, there assembled those members of the court who were consumed by a passion either for gambling or for being seen, which is to say absolutely everyone; and enormous sums – nay, estates, dukedoms, and entire fortunes – were lost and won with the flip of an ace or the toss of a die, the stakes here being considerably heightened above those in the drawing room at Vaugirard. Once Mme Scarron was well ensconced along with her contingent of cardsters, I was happy to learn that my offices to them beneath the tables could continue and even thrive, for indeed, with the new stakes, my list of clientele now expanded well beyond the likes of Mlle Louise-Adélaïde Marsy, Mme Poulaillon, the Archbishop of Lisieux, the Marquis de Feuquières, and others. The Comtesse de Pommeret came to be invariably paired at cards with the queen herself, they both being unutterably stupid at anything more complex than solitaire; and people clamored to play hands opposite them, which flattered their vanities as readily as it emptied their purses. Beyond her inability at cards, rivaled only by her inability at speaking French, the queen had, which is strange, a curious predilection for dwarves; and had collected some five or six of them about her, all of them exceedingly ugly; and she cast an eye upon me, reader, I can tell you, and that more than once. Not caring to appeal for protection to my mistress, who had shown me so little partiality up to that time, and fearing that I would be swept up into her majesty’s hideous entourage and subjected to attentions from her, I knew not what desperate course to take. But for the nonce I was spared; and I pray that it not appear vanity that leads me to speculate that I was simply not ugly enough to suit her wretched taste, and so was spared. Day and night, through the halls of the royal residence, I also witnessed swarms of the general public who were, surprisingly enough, allowed to amble about, observing the comings and goings of the court. Eventually I came to avoid these creatures as much as possible, for I found that they were frequently of the lower classes, and many of them with diseases; and it was said that there were pickpockets amongst them, a consideration which meant little to me, for my pockets being situated so much lower than the artful fingers of your average thief, I felt no threat, and my pockets were empty to boot, except for my handkerchief. Here as well, and aloof from the riffraff, were bevies of princes and princesses, dukes and duchesses, counts and countesses that made up that teeming court of the divine monarch, each of them constantly jostling to be seen by all of the similarly jostling others, but most especially by my lord King Louis Himself and by the second divinity, the most glorious Marquise de Montespan, who were themselves to be seen, though quite unpredictably, about the chateau. Here were elaborate formal balls and fêtes, banquets and divertissements, attended by this restless pack; and these events went late into the night; but alas, I can report but little of them to you, reader, for I was not allowed to be present. For if there were any need of a dwarf or dwarves upon such occasions for the purposes of entertainment for the company, it was the queen’s own set which was sent for, the sight of them being even more ludicrous than of myself, as I have noted. Here I discovered as well were conducted the daily workings of the government itself, the French nation being singularly blessed to have at its head my lord King Louis XIV, to wit, God; which is why in all ways France has far exceeded other nations, none other having at its head of state God; for in this world there can be no other than one, unique God; the matter is self-evident. But many lands – Holland, Spain, the Papal States, Savoy, the Holy Roman Empire – were blind to this, it seems, and fought or sought to fight wars with France; and any blockhead would know that that was a losing proposition: God will easily prevail, and so He did. Yet even so, weighty deliberations were the order of the day in the conduct of the government, and although I never attended any of them, needless to say, yet I would glimpse various impressive officials now and then on their way to and from the Royal Cabinet Chamber, and the doors to that chamber being customarily left open during the meetings, which was an indication of the king’s largesse, the public were allowed to stand off at a distance in the adjoining room and to watch the proceedings though it was almost impossible to hear them. As for myself I had not the leisure. These men, I learned, were busying themselves with many matters, primary amongst them the annihilation of as many enemies of the king as possible, and especially of the Spanish and the Dutch; and secondary, the supervision of divers building projects which were undertaken to display to the world the grandeur of the French throne, reflecting the grandeur of God: among them, the expansion of a small hunting lodge which had been a favorite of King Louis’s father, Louis XIII, in the town of Versailles some twenty miles to the south. The court made increasingly frequent visits to that lodge until at last St. Germain was abandoned (1682) in its favor; and reader, it is where I am at this present writing, at Versailles, and I am high up inside the ceiling of the chapel vestibule, and through the slits of my louver I have a partial view of the gardens below, a series of elaborate flowerbeds, fountains and groves, pathways and promenades, laid out by a certain M. Le Nôtre. But to resume: on Fridays, my lord King Louis met with His confessor in the morning and later in the day with the ecclesiastic Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, who had undertaken the education of my lord’s son the dauphin; in addition to giving His Majesty spiritual counsel at these Friday meetings, Bishop Bossuet also reported to Him what progress the young man was making at his books. But it was rumored that that progress was somewhat slow, the dauphin being a reluctant scholar, even despite a daily round of sharp blows administered by the bishop. Here I found that almost every afternoon there were noisy preparations for the hunt, the king, and those like Him who were devoted to the sport, mounting their steeds to ride off into the forest. I tried to avoid these scenes, for the dogs, anticipating the exuberance of the chase and, more to the point, of the kill, would by then have whipped themselves into a slathering frenzy, their teeth bared, their ice-cold eyes full of malice. No: I stayed away; and having no duties to perform for those preparations, it was not difficult. Here, finally, reader, were musicians. And I recall my first impression of them, that these men appeared to be huge; indeed, much larger than the Turks I have told you of and the Indians, larger than the government officials, larger even than the Archbishop of Lisieux; but not of course larger than God. But it was perhaps my imagination and wonderment at them that fixed that impression of grandeur into my brain. Whenever His Majesty dined or whenever He called for entertainment, which was most frequent for it turned out that He was devoted to music, here came forth these giant men with their flutes, violins, violes da gamba, lutes and oboes, with their bassoons and cellos and their harpsichords; and they would set themselves off into a thick cluster at one end of a chamber; whereupon they would begin applying themselves to their instruments, striking them or blowing into them or plucking at them, or sawing at them with strips of wood and gut; and they would do so all together, all at once as it were, each adhering to the speed and rhythms of all the others though himself playing a different melody; and it was frightening, reader, for the brilliant roar which they set up! and the room would grow quite full of it, some of the sounds being shrill and reedlike, but the others! the others were deep and quaking and thunderous; and as they all played simultaneously, which was the wonder of it, the pitch became magnified, and the dark, ripe vibrations resonated throughout the entire place with such beauty and splendor, with such sublimity, that I feared – nay, I was certain – that they had put devils inside their instruments, for I doubted any human beings upon this earth capable of such effects. And so I kept my distance; and indeed I am certain that upon more than one occasion, far across the room, I spied, from within the crescent-shaped sound hole of a double-bass viol, a pair of eyes looking out at me; and I would run away or hide behind some fringe or tassel, trembling. Now you should know that these activities which I have described were often interrupted, for my lord King Louis was much given to traveling from one royal residence to another, there being four or five in the area; and whenever He went, the daily routines ceased abruptly, and the entire court went with Him; and a great deal of time was then spent packing, transporting, and unpacking the needs of the court. Athénaïs, the Marquise de Montespan, the divine, accompanied Him on these sojourns, being in constant attendance upon Him; and the queen would travel with Him as well; and occasionally even the children, Louis-Auguste, Louis-César, and the infant Louise-Françoise, would be taken along as though for the ride, in which case their governess Scarron would accompany her brood. A more delicate situation would arise when King Louis's travels took Him off to war, out to the front lines, most often in the Flanders region. It would seem a straightforward enough matter that on such excursions the king would be attended by the appropriate military personnel and such civilians as He would require at the battle area; and so it was. But as well, there developed a custom of inviting along certain ladies to join His Majesty on these expeditions. The queen Marie-Thérèse would be routinely included, even though as often as not our forces were engaged in slaughtering as many of her Spanish compatriots as they could set hands to; but it was no matter, for it was unlikely that she understood anything of what was going on outside her carriage in the first place. Increasingly, though she had not yet achieved any official capacity at the court, Athénaïs, the divine marquise, would, again, be in attendance to my lord King Louis, though indeed her presence cannot have much pleased the queen. And as well, there was a number of other ladies, as it turned out, who, being in some favor with His Highness at one time or another, for my lord did indeed like the ladies, would or would not be enrolled on the invited list, their inclusion being an indication of the state of their favor, and similarly their exclusion, whether that favor had not yet attained full bloom or had decidedly gone to seed; and I cannot think that their presences can have much pleased either the Marquise de Montespan or the queen. (One such was a lady named Louise de la Vallière, of whom you will hear more later.) And thus there was often some controversy and squabbling surrounding the trips to the troops, which my lord, in His infinite wisdom, would invariably arbitrate with evenhanded justice, if not always to everyone's complete satisfaction. I was privileged to witness one such adjudication by my lord from the hallway adjoining the Cabinet Chamber, where a gathering of family and dignitaries had taken place shortly before a royal excursion to the city of Ghent. It was not itself an official government meeting – as would have been routinely observable by the public from afar – but had emerged from a previous such meeting and hence, perhaps not by design, the cabinet doors had been left open. At issue on this occasion were not the ladies, for the queen, Montespan, Vallière, and a saucy young thing, a certain Mlle Le Borgne, had been assembled to make the trip; but rather the issue was the three children, all present as well in the chamber, Louis-Auguste, Louis-César, and Louise-Françoise, all crawling around in the middle of the floor to the obvious discomfort of their governess. And the wisdom of taking three babes off to the front lines was much debated, the military representatives there and Scarron all speaking strongly against it, while Montespan saw it as an agreeable outing and an educational opportunity, especially for the boys. It was difficult from the distance at which I stood to distinguish clearly everything that was said in the chamber, and I inched forward to stand behind a large urn so that I might overhear the deliberations (I shall not say “spy upon”, though you may draw what conclusions you care to); and now the powerful voice of the Duc de Luxembourg reached me easily enough: "Our rear guard units can ensure only minimal security on or near the battle lines; Captain Oizel feels that it is less than responsible to risk the lives of the – ah – little ones” – and he did not like to state exactly whose little ones he was speaking of – “of the children, I say, in areas adjacent to the fury of the hostilities. With all respect." "¿Por qué los niños querrían mirar una batalla tediosa?” asked the queen, but no one understood her and no one replied. Mme Scarron, however, seized upon the duke's observation. "Sir,” said she to that gentleman, “I thoroughly concur with the excellent Captain Oizel's assessment. It is altogether more fitting that the children stay here with me. Moreover, they can have no interest in battles and warfare and such-like affairs." At which point, Louis-Auguste struck Louis-César a sharp blow to the stomach. “And is your excellent Captain Oizel oblivious then to exposing the lives of the ladies to risk?" now spoke the divine Marquise de Montespan. "There's no earthly good in going to the front if we aren’t to be close enough to enjoy the mayhem.” “Indeed, the ladies may expose themselves to risk quite freely, madame,” Luxembourg replied with a curt bow in her direction, “and in full knowledge of the dangers. These children, however, can make no such judgments.” “Indeed, commander,” replied the marquise, “just so: it is the duty of parents to make judgments for their children – one does it every day, sir.” "I should say," interjected Mme Scarron, now holding the two Louis at bay, "that it is the duty of parents to make prudent judgments for their children." She stared smugly at the marquise. "Tosh! I have been to the front," retorted the divinity. "It is as safe as sitting in a drawing room with friends." "Which is not in fact altogether a safe thing to do," snapped Scarron. The marquise smiled: "I spoke, my dear Scarron, from my own experience." But the governess chose rather to ignore this remark than to allow the conversation to veer thus off course. "Children of four years old – of two – will gain nothing from being carted off into battle and can indeed only be an encumbrance to any responsible military command." "I take madame's point entirely," Luxembourg now spoke up again, seeking to end the debate. "The babes must not be exposed needlessly to danger." And now, my lord King Louis – divine presence, radiant power, illustrious majesty, seated in the far rear of the chamber – at last, my lord spoke out, for He had up to that point engaged in none of the debate; and He said: "Children," at which all three babes – Louise-Françoise, infant, included – left off attacking one another and gave instant ear, "you shall keep with your mother." At that – and although at the king's command Scarron had bent forward to take the children's hands – Louis-Auguste rose on his unsteady four-year-old feet and without a moment's hesitation, hobbled his way across the length of the chamber to where the Marquise de Montespan stood; and he reached out and clutched at her skirts; and Louis-César immediately followed suit; and even Louise-Françoise began rolling forward in the same general direction. Excellent well done, Louis-Auguste – yet again! thought I from my post behind the urn. I have taught you well, my lad. And well have you learned. The marquise's face was wreathed in happy smiles, and yet tears filled her beautiful eyes as she lifted Louis-Auguste up into her arms and kissed him gently on his cheeks; nor was that lady unaware as she did so, of the buzz that swept through the assembly at Louis-Auguste's innocent act of honesty. In the middle of the room, for the first time that I could recall, Mme Françoise Scarron now lived up to her famous nickname, that of “Indian princess”, for that lady's face, contorted into a tight scowl, became as scarlet red as any Indian's you may imagine! And thus, reader, by a child's simple gesture, the truth – already well known to everyone there – had at last been publicly and incontrovertibly stated, and the divine marquise's love for her own dear children most movingly and openly expressed. They accompanied their mother to Ghent and returned, in a fortnight, unscathed. Reader: given the exalted status of the persons within that gathering – and I include the three half-regal infants crawling about on the floor – I did not think it seemly at that moment to take any pleasure, even privately within my own breast, at the thought that I, Hugues, humble servant, had played a hand, however modest, however slight, however unacknowledged, in the affairs of the royal state of France; even when that hand was for the benefit of the divine marquise and at the expense of the conniving Scarron. Nor to this day do I think it seemly to take any such pleasure; and thus I shall make no further comment upon it.Discussion Questions

From the author:1) What set you off writing this book?

2) How close to historical accuracy is it?

3) Is the character of Hugues real, fictional, based on someone?

4) Is the portrayal of Louis XIV accurate? Of his mistresses? Of his brother?

5) Could you talk about the practice of saying black Masses? About the affaire des poisons?

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

A Note from Paul to BookMovement members: Everyone’s notion of the baroque, theatrical Versailles of Louis XIV is of a high point in European civilization. But I’m fascinated by the darker, seamier side – the rough politics, the sex, the scandals – even the occult. And I thought: what if some small, innocent creature got caught in the tangles of that huge and not-at-all innocent world? And suppose he maneuvered his way into its innermost circles – to Louis himself, his mistresses, the political giants of the day? Which is what my unsuspecting dwarf does – along the way unearthing his true identity – a bombshell revelation that threatens the foundations of the French monarchy. All this is not without its comic angle. The hero’s escapades – from underneath card tables – helping gamblers cheat puts him within earshot of some wickedly funny court gossip. And the cast includes some ridiculously extravagant players. “Brilliant irony and dark humor of the sort Mark Twain achieved,” one reviewer wrote. Another compared it to Swift and Rabelais: “There is a loveable naivety, and there is optimism…which endears our physically abbreviated hero to the reader. Inspired by the author’s friendship with Hervé Villechaize – the dwarf on TV’s ‘Fantasy Island’ – Weidner’s sympathy and accurate knowledge of the problems of dwarf-hood shine through.”Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more