BKMT READING GUIDES

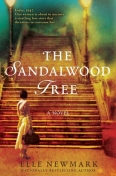

The Sandalwood Tree: A Novel

by Elle Newmark

Hardcover : 368 pages

5 clubs reading this now

1 member has read this book

In 1947, Evie Mitchell is living in India with her emotionally distant husband and young son ...

Introduction

From incredible storyteller and national bestseller Elle Newmark comes a sweeping novel that brings to life two love stories, set ninety years apart against the rich backdrop of war-torn India.

In 1947, Evie Mitchell is living in India with her emotionally distant husband and young son amidst the violence surrounding the end of British rule. When Evie discovers a packet of old letters written by two young Englishwomen who lived in the same house in 1857, she embarks on a mission to uncover their stories, leading her through the bazaars and temples of a British hill station and beyond. As the country fights for independence, Evie struggles to save her strained marriage while piecing together her Victorian ghosts, searching for answers.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1947 Our train hurtled past a gold-spangled woman in a mango sari, regal even as she sat in the dirt, patting cow dung into disks for cooking fuel. A sweep of black hair obscured her face and she did not look up as the passing train shook the ground under her bare feet. We barreled past one crumbling, sun-scorched village after another, and the farther we got from Delhi the more animals we saw trudging alongside the endless swarm of people—arrogant camels, humpbacked cows, bullock-drawn carts, goats and monkeys, and suicidal dogs. The people walked slowly, balancing vessels on their heads and bundles on their backs, and I stared like a rude tourist, vaguely ashamed of my rubbernecking—they were just ordinary people, going about their lives, and I sure as hell wouldn’t like someone staring at me, at home in Chicago, as if I were some bizarre creature on exhibit—but I couldn’t look away. The train stopped for a cow on the tracks, and a suppurating leper hobbled up to our window, holding out a fingerless hand. My husband, Martin, passed a coin out the window while I distracted Billy with an impromptu rib-tickle. I blocked his view of the leper with my back to the window and smiled gamely as he pulled up his little knees and folded in on himself, giggling. “No fair,” he gasped. “You didn’t warn me.” “Warn you?” I wiggled two fingers in his soft armpit and he squealed. “Warn you?” I said. “Where’s the fun in that?” We wrestled merrily until, minutes later, the train ground to life and we pulled away, leaving the leper behind, salaaming in his gray rags. Last year, early in 1946, Senator Fulbright had announced an award program for graduate students to study abroad, and Martin, a historian writing his Ph.D. thesis on the politics of modern India, won a scholarship to document the end of the British Raj. We arrived in Delhi at the end of March in 1947, about a year before the British were scheduled to depart India forever. After more than two hundred years of the Raj, the Empire had been faced down by a skinny little man in a loincloth named Gandhi and the Brits were finally packing it in. However, before they left they would draw new borders, arbitrary lines to partition the country between Hindus and Muslims, and a new nation called Pakistan would be born. Heady stuff for a historian. Of course I appreciated the noble purpose behind the Fulbright—fostering a global community—and understood the seriousness of partition, but I had secretly dreamed about six months of moonlit scenes from The Arabian Nights. I was intoxicated by the prospect of romance and adventure and a new beginning for Martin and me, which is why I was not prepared for the grim reality of poverty, dung fires, and lepers—in the twentieth century? Still, I didn’t regret coming along; I wanted to see the pageant that is Hindustan and to ferret out the mystery of her resilience. I wanted to know how India had managed to hold on to her identity despite a continuous stream of foreign conquerors slogging through her jungles and over her mountains, bringing their new gods and new rules, often setting up shop for centuries at a time. Martin and I hadn’t been able to hold on to the “us” in our marriage after one stint in one war. I stared out of the open window, studying everything from behind my new sunglasses, tortoiseshell plastic frames with bottle-green lenses. Martin wore his regular glasses, which left him squinting in the savage Indian sun, but he said he didn’t mind; he didn’t even wear a hat, which I thought foolish, but he was stubborn about it. My dark-green lenses and my wide-brimmed, straw topee gave me a sense of protection, and I wore them everywhere. We passed pink Hindu temples and white marble mosques, and I raised my new Kodak Brownie camera up to the window often, but didn’t see any hints of the ancient tension simmering between Hindus and Muslims—not yet—only the impression that everyone was struggling to survive. We passed mud-hut villages, inexplicable piles of abandoned bricks, shelters made from tarps draped haphazardly over bamboo poles, and fields of millet stretching away into mist. The air smelled like smoke tinged with sweat and spices, and when gritty dust invaded our compartment, I closed the window, brought out the hairbrush, washcloth, and diluted rubbing alcohol that I carried in my hand baggage and went to work on Billy. He sat patiently as I whisked his clothes, wiped his face, and brushed his blond hair till it shone. By then the poor child had gotten used to my neurotic need for cleanliness, and if you understand the lunatic nuances involved in keeping up appearances you’ll understand why I spent an insane amount of time fighting dust and dirt in India. I caught the madness from Martin. He had come home from the war in Germany obsessed with a need for calm and order, and by the time we had dragged ourselves halfway around the world to that untidy subcontinent I was cleaning compulsively, drowning confusion in soapy water, purging discontent with bleach and abrasive cleansers. When we arrived in Delhi, I shook out the bed linen on the tiny balcony of our hotel room before I let my weary husband and child go to sleep. In the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, crammed with people and rickshaws and wandering cows, I pinched my nose against the smell of garbage and urine and insisted Martin take us back to the hotel, where I checked under the bed and in the corners for spiders. Found a couple and smashed them flat—so much for karma. When we boarded the train to go north, I wiped down the seats in our compartment with my ever-ready washcloth before I let Martin or Billy sit. Martin gave me a look that said, “Now you’re being ridiculous.” But the tyranny of obsession is absolute and will not be reasoned with. At every stop, chai-wallahs, water bearers, and food vendors leaped onto the train and sped through the carriages hawking biscuits, tea, palm juice, dhal, pakoras, and chapatis, and I recoiled from them, keeping a protective arm around Billy while shooting a warning look at Martin. At the first few stops, mingled smells of grease and sweat saturated the sweltering air and made the food unappealing. But after several hours without eating, Martin suggested we try a few snacks. I quickly produced the hotel sandwiches I’d packed in Delhi and handed him one, agreeing only to buy three cups of masala chai—gorgeous, creamy tea infused with cloves and cardamom—because I knew it had been boiled. I ate my bacon sandwich and drank my tea, feeling safe and insulated—I would observe and understand India without India actually touching me. But, munching away and looking out the window, my heart beat faster at the sight of an elephant lumbering on the horizon. A mahout, straddling the massive neck, urged the animal along with his bare heels, and I watched, strangely exhilarated, until they disappeared in a trail of red dust. Billy watched women walking along the side of the road with brass pots balanced on their heads and men bent double under enormous loads of grain. Often, ragged children straggled behind, looking thin and exhausted. Quietly, he asked, “Are those poor people, Mom?” “Well, they’re not rich.” “Shouldn’t we help them?” “There are too many of them, sweetie.” He nodded and stared out the window. On our first day in Masoorla I threw open the blue shutters of our rented bungalow, beat the hell out of the dhurrie rugs, and polished all the scarred old furniture. I went over every inch of the old, two-bedroom house with carbolic soap and used a quart of Jeyes cleaning fluid in the bathroom. Martin said I should get a sweeper to do it, but how could I trust a woman who spent half her time up to her elbows in cow dung to clean my house? Anyway, I wanted to do it. I didn’t know how to fix my marriage, but I knew how to clean. Denial is the first refuge of the frightened, and it is possible to distract oneself by scrubbing, organizing, and covering smells of curry and dung with disinfectant. It works—for a while. When I found the hidden letters, I had just finished an assault on the kitchen window. I squeezed out the sponge and stood back, squinting with a critical eye. A yellow sari converted to curtains framed the blue sky and distant Himalayan peaks, which were now clearly visible through the spotless window, but the late-afternoon sun spotlighted a dirty brick wall behind the old English cooker. The red brick had been blackened by a century of oily cooking smoke and, just like that, I decided to roll up my sleeves and give it a good scrub. Rashmi, our ayah, deigned to wipe off a table or sweep the floor with a bunch of acacia branches, but I would never ask her to tackle a soot-encrusted wall. A job like that fell well beneath her caste, and she would have quit on the spot. The university chose that bungalow for us because it had an attached kitchen instead of the usual cookhouse out back. I liked the place as soon as I walked into the little compound full of tangled grass and pipal trees with creepers twisting around their trunks. A low mud-brick wall, overgrown with Himalayan mimosa, circled our compound with its hundred-year-old bungalow and vine-clad verandah, and an old sandalwood tree, with long oval leaves and pregnant red pods, presided over the front of the house. Every-thing had a weathered, well-used look, and I wondered how many lives had been lived there. Off to one side of the house, a path bordered by scrappy boxwood led to the godowns for the servants, a dilapidated row of huts, far more of them than we would ever need for our small staff. At the far end of the godowns a derelict stable nestled in a grove of deodars, and Martin talked about using it to park our car during the monsoon. Martin had bought a battered and faded red Packard convertible, which had been new and snazzy in 1935 but had seen twelve monsoons and too many seasons of neglect. Still, the jalopy ran, I had a bicycle, Billy had his red Radio Flyer wagon, and that’s all we needed. The remains of the old cookhouse still stood around back, listing under a neem tree, a bare little shack with a dirt floor, one sagging shelf, and a square of mud bricks with a hole in the center for wood or coal. Indians didn’t cook inside colonial houses—a fire precaution and some complicated rules having to do with religion or caste—and it must have been some very unconventional colonials who decided to attach a kitchen to the main house and install a cooker, bless their hearts. I hired our servants myself, choosing from a virtual army that lined up for interview. They presented their chits—references—and since most of them couldn’t read English they didn’t realize that the bogus chits they had bought in the bazaar might be signed by Queen Victoria, Winston Churchill, or Punch and Judy. The only chit I could be absolutely sure was authentic said, “This is the laziest cook in all India. He strains the milk through his dhoti and he will rob you blind.” In the end we had a scandalously small staff—a cook, an ayah, and a dhobi who picked up our laundry once a week in silent anonymity. At first, we’d also had a gardener, a sweeper, and a bearer—a more typical arrangement—but that many servants made me feel superfluous. I particularly disliked having a bearer, a sort of majordomo who trailed around after me, doing my bidding or passing my orders on to the other servants. I felt helpless as a caricature of a nineteenth-century memsahib, swooning on a daybed. Our bearer had been trained in British households and would wake Martin and me in the morning with a tradition called “bed tea.” The first time I opened my eyes to see a dark, turbaned man standing over me with a tray it scared me out of my wits. He also served our meals and stood behind us while we ate; it felt like sitting in a restaurant with an eavesdropping waiter, and I was painfully conscious of our conversation and my table manners. I found myself delicately dabbing the corners of my mouth and keeping my spine straight. I could see that Martin felt it, too, and meals became an uncomfortable chore. I didn’t want “bed tea,” I didn’t want a bearer—always there, always hovering—and I enjoyed feeling useful. So I kept our little house clean and watered the plants on the verandah myself. I liked the natural jungly look around the bungalow, and the notion of our having a gardener struck me as absurd. Martin told me the expatriate community was appalled by our lack of servants. I said, “So?” I kept the cook, Habib, because I didn’t recognize half the things in the market stalls, and since I didn’t speak Hindi, the price of everything would have tripled. I kept Rashmi, our ayah, because I liked her and she spoke English. When I first met Rashmi, she greeted me with a formal bow, her hands in an attitude of prayer. She said, “Namaste,” and then began giggling and clapping, making her chubby arms jiggle and her gold bangles jangle. She asked, “From what country are you coming?” I said, “America,” wondering if it was a trick question. “Oooh, Amerrrica! Verryy nice!” The ruby in her right nostril twinkled. Rashmi deeply disapproved of a household with so few servants. Whenever she saw me beating a rug or cleaning the bathroom she would hold her cheeks and shake her head, her eyes round and alarmed. “Arey Ram! What madam is doooiiing?” I tried to explain that I liked to keep busy, but Rashmi would stomp around the house mumbling and shaking her head. Once I heard her say, “Amerrrican,” as if it were a diagnosis. She started sweeping up with neatly tied acacia branches and taking out the garbage. I had no idea where she took it, but it seemed to make her happy to do it. Whenever I thanked Rashmi for something, she would waggle her head pleasantly and say, “My duty it is, madam.” I wished Martin and I could accept our lot so easily. My beautiful Martin had come home from the war with a shrouded, chaotic underside, wanting everything as neat as an army cot. It was about control, I know that, but he drove me nuts, picking at imaginary lint on my clothing and lining up our shoes side by side on the closet floor, like a row of soldiers snapped to attention At first I complied and kept everything shipshape, simply because we didn’t need yet another thing to argue about. But I soon discovered that ordering furniture and annihilating dust gave me a fragile sense of control—Martin was on to something there—and I enjoyed imposing my antiseptic standards on India, keeping my little corner of the universe as predictable as gravity. When this altered Martin came home from Germany, straightening books on the shelf and buffing his shoes until they screamed, he often complained of a metallic taste in his mouth, rushing off to brush his teeth five times a day. I didn’t know what he tasted, but I did know he had nightmares. He twitched in his sleep, muttering disjointed bits about “skeletons” and calling out names of people I didn’t know. Some nights he’d shout in his sleep, and I’d spring up, shocked and scared. I’d dry the sweat from his face with the sheet and kiss the palms of his hands while his breathing calmed and my heart slowed. His skin would be clammy and he’d be trembling, and I’d rock him and croon in his ear, “It’s all right. I’m here.” After a while, when it seemed safe, I’d say, “Sweetheart, talk to me. Please.” Sometimes he’d talk a little, but only about the language or the landscape or the guys in his platoon. He said it bothered him that German sounded so much like the Yiddish of his grandparents; then he shook his head as if he was trying to understand something. He told me that Germany was littered with castles and fairytale villages, all blasted to hell. He said the soldiers in his platoon were an unlikely bunch thrown together by war, men who would not otherwise have met. Martin, a budding historian, bunked with a fast-talking mechanic from Detroit named Casino. Also in his barracks were an American Indian named William Who Respects Nothing, and a Samoan named Naikelekele, whom the men called Ukulele. Martin said they were OK guys, but a CPA from Queens named Polanski—Ski to the guys—had the wide slab face and flat blue eyes behind too many of the pogroms mounted against the Jews, and Martin had to keep reminding himself that they were on the same side. But Ski cheated at cards and had a nascent anti-Semitic streak. Martin said, “Of all the decent guys in that platoon I had to haul Ski back to a field hospital while better men lay dead around us.” His ambivalence about saving Ski haunted him, but it wasn’t the thing eating at him like acid. One night, in bed, after having had an extra glass of wine with dinner, Martin knit his fingers behind his head and told me about a mess sergeant from the hills of Appalachia, Pete McCoy, who made a crude liquor with pilfered sugar and yeast and canned peaches. Pete had served an informal apprenticeship at his father’s still, deep in the woods of West Virginia, and in a rare, lighthearted moment, Martin did a skillful imitation. He drawled, “Ah know it ain’t legal. But mah daddy’s gonna quit soon as he gits a chance.” I said, “The nightmares aren’t about Pete McCoy’s moonshine.” “Hey, you didn’t taste that stuff. Burned like a son-of-a-bitch going down.” His voice became abstract. “But sometimes the moonshine was necessary, like when Tommie . . . Well, anyway, McCoy was like the medic who brought the morphine.” I said, “Who was Tommie?” Martin looked away. “Ah, you don’t want to hear that stuff.” “But I do. Talk to me. Please.” He hesitated, then, “Nah. Go to sleep.” He patted my hand and rolled away. World War II veterans were icons of heroism, brave liberators, and most of them were glad to leave the ugliness buried under the war rubble and get back to a normal life, or try to. But Martin had come home with invisible wounds, and our normal life was as ruined as the German landscape. I wanted to understand. I’d been begging him to talk for two solid years, but he wouldn’t budge. He wouldn’t let me help him, and I felt worn to a stump from trying. That business of rolling away from me in bed hurt, but by the time we got to India, I was doing it, too. I was becoming as frustrated as he was tormented, and we took our pain out on each other. We hid in our respective corners until something brought us out with fists raised. I couldn’t fix our insides, so I fixed our outside. I prowled around the bungalow searching for dust mites to exterminate, mold to slaughter, and smudges to wipe out. I vanquished dirt and disorder wherever I found it and it helped, a little. The morning I found the letters, I’d filled a pail with hot soapy water and pounced on the sooty bricks behind the old cooker with demented determination. I described foamy circles on the wall with my brush and . . . what? One brick moved. That was odd. Nothing in that house ever rattled or came loose; the British colonials who built the place had expected to rule India forever. I put the brush down and forced my fingernails into the crumbling mortar around the loose brick, then wiggled it back and forth until it came out far enough for me to get a grip on it. I teased the brick out of the wall and felt a thrill of discovery when I saw, hidden in the wall, a packet of folded papers tied with a faded and bedraggled blue ribbon. That packet reeked of long-lost secrets, and I felt a smile lift one corner of my mouth. I set the blackened brick on the floor and reached in to lift my plunder out of the wall. But on second thought, I went to the sink first to wash the soot from my hands. With clean, dry hands, I eased the packet out of its hiding place, blew the dust from its crevices, then laid it on the kitchen table and pulled the ribbon loose. When I opened the first sheet, the folds seemed almost to creak with age. Gently now, I smoothed the fragile paper out on the table and it crackled faintly. It was ancient and brittle, the edges wavy and water-stained. It was a letter written on thin, grainy parchment, and feminine handwriting rose and swooped across the page with sharp peaks and curling flourishes. The writing was in English, and the way it had been concealed in the wall hinted at Victorian intrigue. I slipped into a chair to read.Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions from the Publisher:1. THE SANDALWOOD TREE takes place in a very interesting place, India, at two fascinating time periods in the country’s history—the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857 and Britain’s withdrawal from control in1947. What made you choose this setting and these moments in time? What research did you do in writing the novel?

2. What draws you to the genre of historical fiction? Does the mixture of history and storytelling pose a challenge? Do you enjoy reading historical novels in addition to writing them?

3. The Victorian era mysteries surrounding Adela Winfield and Felicity Chadwick are unveiled through a series of letters Evie Mitchell uncovers almost a century later while living in the same home in India with her husband and young son. How were these women’s lives different? What challenges did they share in common? Did you prefer writing one storyline or set of characters to the other?

4. One of the major themes of THE SANDALWOOD TREE is the resilience of the Indian people. When Evie first arrives in India, she says “I wanted to… ferret out the mystery of [India’s] people. I wanted to know how India managed to hang on to her identity in spite of multitudes of foreign conquerors slogging through with new gods and new rules.” Do you think this ability to “bend without breaking” is universal to human nature or unique to the Indian people? Something developed over time out of necessity?

5. The British characters often mock the Indians’ superstitions throughout the novel. Is Evie’s need for order a superstition in itself? Do you think there’s a difference between her need for order and the natives’ need for their rituals? Are they driven by the same impulses and desires?

6. Felicity and Adela live in a time where a woman had very few choices, and society had very specific expectations of them. In spite of these, they manage to carve out nontraditional lives, vowing to “scrap the rules and live a life of joy, no matter what the price.” What do you think makes them different from the other women of the era, able to make these choices? Do you think the price they paid for those choices was too high?

7. Throughout THE SANDALWOOD TREE there is a huge dichotomy between the rich foreigners, with their servants and extravagance, and the abject poverty of so many of the natives. Did this disparity bother you? Do you think it’s inevitable that there be such a difference between classes?

8. Both your first novel, The Book of Unholy Mischief, and THE SANDALWOOD TREE combine your love of food and travel. Tell us about these pastimes and the trips and adventures you may be planning for your next novel.

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

Note from author Ellen Newmark: After reading Of Mice and Men for the first time I sat staring into space, the book splayed open on my lap, devastated, until I remembered it was a novel. He made it up! Then I got excited. How had John Steinbeck ripped my heart out with a story about people who didn’t even exist? Needing an answer not only made me want to write, it made me want to write well. My first novel, The Chef’s Apprentice, was a call to pay attention. Too many people go through life like sleepwalkers, protecting themselves from unpleasantness in any form. What a waste! What a pity to miss your own life. The Chef’s Apprentice was a challenge to readers to pay attention, and a challenge to myself to put that message in the context of a good story. My second novel, THE SANDALWOOD TREE, addresses larger issues: love and war, on the small stage of family, and on the global stage of world power. I would like readers of THE SANDALWOOD TREE to see that the same wars are fought for the same reasons over and over again, and everyone believes God is on his side. Personally, I wouldn’t trust a god who would let people believe that.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more