BKMT READING GUIDES

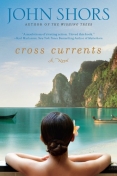

Cross Currents

by John Shors

Paperback : 352 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

“A master storyteller.” – Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club

“I’m deeply moved by his work.” – Wally Lamb, bestselling author of She’s Come ...

Introduction

“A maelstrom of riveting action. I loved this book.” — Karl Marlantes, bestselling author of Matterhorn

“A master storyteller.” – Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club

“I’m deeply moved by his work.” – Wally Lamb, bestselling author of She’s Come Undone

Thailand's pristine Ko Phi Phi island attracts tourists from around the world. There, struggling to make ends meet, small-resort owners Lek and Sarai are happy to give an American named Patch room and board in exchange for his help. But when Patch's brother, Ryan, arrives, accompanied by his girlfriend, Brooke, Lek learns that Patch is running from the law, and his presence puts Lek's family at risk. Meanwhile, Brooke begins to doubt her love for Ryan while her feelings for Patch blossom.

In a landscape where nature's bounty seems endless, these two families are swept up in an approaching cataclysm that will require all their strength of heart and soul to survive...

Excerpt

Saturday, December 18 Consequences Lek opened his eyes, though his body remained as still as the gecko on the ceiling. He watched it, as he often did, admiring its patience, aware of its seemingly perpetual hunger. The creature was the length of his forefinger, and the color of mahogany. Lek enjoyed gazing at the gecko, though he was jealous of its speed. If a moth landed nearby, the gecko moved as if lightning filled its veins. Yet in the absence of insects, the gecko was without motion, a silent sentinel that protected Lek’s home from airborne invaders. As he did every morning, Lek studied the mosquito net that covered him, his wife, and their baby daughter. The old net had been patched in several places, but today no such work was needed. The net remained intact and impenetrable—a necessary barrier between their skin and the denizens of the hot, humid air. Lek looked at his wife, Sarai, who slept facing him, their daughter between them. Sarai’s small frame seemed as still as the gecko. Like most Thai women of her generation, she slept in her bra and panties, which were visible beneath thin cotton pajamas. As usual, she had pulled back her shoulder-length black hair and bound it behind her head. Reminding Lek of the moon, Sarai’s face was full and round and somewhat flat. Her skin was the color of wet sand. Laugh lines bordered either side of her mouth—a sight that pleased him as much as any. Resisting an impulse to kiss their daughter, Lek remained still. Only seven months old, Achara slept in a cloth diaper and nothing else. During the day she was almost always naked, but at night the diaper helped keep their thin mattress dry. Like her parents, Achara was slight and small boned. Lek was proud of her thick black hair, of how she smiled when he whispered and tickled her belly. Though he lived in a beautiful place, and saw splendor each day, nothing was lovelier than his little girl, or her older brother and sister, who slept together in their nearby room. “Why are you smiling?” Sarai asked quietly in Thai, stirring enough so that the mosquito net rippled. “She’s getting bigger.” “Of course she is. She suckles like those Germans eat—as much food as I can give her.” His fingers edged forward, touching Sarai’s shoulder, stroking her soft skin. “I wish I could help.” “Oh, what would you know about it? Women have suffered for thousands of years while you men have dreamed away.” “Come outside. We need to talk. Remember?” “I remember everything. Best that you remember that.” He shook his head, smiling, easing out from beneath the net, changing into red shorts and a frayed gray T-shirt. Sarai put on a purple sarong and a light green collared blouse. After stepping out of their small room and into another, Lek looked at their other children, who also slept beneath a net. Their son’s arm lay across their daughter’s belly, and Lek was pleased by the proximity of their bodies. Most of the narrow mattress was vacant. A few feet from their children, under a different net, slept Sarai’s mother, who was facing the nearby wall. Outside their three-room home, dawn was beginning to unfurl. The mountain behind them blocked the sun’s tendrils of orange and amber, and the sky was a juxtaposition of blue and black hues. The nearby bay was smooth, more like the surface of a giant cup of coffee than an opening to the sea. Rainbow Resort, which Lek and Sarai owned and operated, was a collection of eleven bungalows and a restaurant situated at the far northern end of a long beach. The bungalows were mainly thatch and bamboo, featuring ceiling fans, showers, double beds, and hand-flushing toilets, but little else. The open-sided restaurant was part cinder block and cement, with a thatched roof and a wooden railing. Bamboo tables and chairs occupied much of the restaurant, which included a bar, a fish tank, and several ceiling fans. For the most part, travelers used the restaurant only during heavy rains. Otherwise, Sarai encouraged people to eat outside, on the beach, where she had positioned eight low tables atop colorful tapestries. Lek and Sarai’s home was on the northern side of the restaurant, opposite the bungalows. Their sleeping quarters were only a few feet from the black, jagged boulders that marked the end of the beach. After following a path that climbed above the boulders, Lek sat down on an old teak bench, moving slowly, the bones of his right hip seeming, as usual, to grind against each other. When Sarai sat beside him, he pointed to the roof of one of their bungalows. “See how Patch fixed it?” he asked, speaking softly, which was his custom. “He climbed up there with new thatch and mended it just right.” Sarai sighed, her breath leaving her mouth as if she were trying to extinguish a candle. “I have the eyes of a kingfisher, you know. The kingfisher sees a shiny minnow. I see a fixed roof.” “He asked me if he could fix it. I didn’t even—” “He’s been here for five months. Five. That makes him illegal. What or who is he hiding from?” “I don’t know.” She started to reply but rubbed her brow instead, sand already on her fingers. “We’re standing on top of a cliff. Do you know that? The wrong step, and down we go.” “But we won’t make that step. We—” “Down, down, down. We’ve got no money. And our bungalows are falling apart and mostly empty. What would happen if the police found him hiding here, working for us? You’d go to jail, and the children, my mother, and I would . . . We would have to leave for Bangkok. We’d be destitute. Is that what you want?” Lek closed his eyes at the thought of such a fate. “No. But . . . but my hip. I can’t work like I used to. I can’t fix roofs or walls or foundations. He’s helping me. All he wants is a room and some food. And he’s nice to the children.” “He’s wonderful with the children.” “It’s good for them to see a foreigner here, working hard, not just lying on the beach and sleeping. And their English. It’s so amazing. They’re learning for free, and that will help them do whatever they want in life.” Laughter emerged from a distant bungalow, and Sarai wondered which of their few residents were up, and what they were doing. “You’re going to turn my hair gray—you know that?” “I—” “Is that what you want? To age me ten years?” “His brother is coming tomorrow. All the way from America. Coming to help him.” Sarai shifted on the bench, listening for their baby and their children. “I like Patch. He’s as sweet as sugarcane to all of us. But just because he’s sweet doesn’t mean that bad things can’t happen. If one of our neighbors talks, if the police come, they’ll take you away. Do you understand that? They’ll take you and Patch away together. And then it won’t matter if Suchin and Niran can speak English so well. It won’t matter because their father will be gone.” “Shhh. Don’t get upset. You’re more than I can handle when you’re upset.” She scowled. “I’m always more than you can handle.” “True.” “But you’re smart to bring this up now, while I’m still sleepy and open-minded. In a few hours you wouldn’t have a chance. You’d have better luck fishing for elephants.” “No one’s going to talk. Everyone likes him. And nobody trusts the police.” Somewhere above, a tree frog beeped, its cry a high-pitched sound resembling the horn of a distant motorbike. “You really need him?” Sarai asked, then remembered that she had to buy fresh bananas for her pancakes. She had better get going. While she was at the market, she’d also purchase stalks of lemongrass, tomatoes, onions, eggs, cucumbers, and condensed milk. Everything else she needed to feed her customers and loved ones, she already had. As Lek thought about his reply, Sarai studied his face, which was more angular than hers. His features were almost boyish—full lips that seemed to linger in a perpetual smile, a narrow forehead free of worry lines, hair and eyebrows as dark as oil, and shiny cheeks that rarely needed a razor. “I need him,” Lek finally replied, “at least until we catch up on all the repairs. Then he can go somewhere else.” “How long will that take?” “A few more weeks. No more, I promise.” Her fingers tightened around his. “I don’t want us to leave here. I’m so afraid of leaving. What would we do?” “We’ll—” “The children. They’d be broken.” “We’ll find a way. We always have. Once the rooms are fixed, we can raise our rates. Raise them by . . . maybe fifty baht a night.” “That’s too much. Thirty, maybe.” “But everyone’s charging more these days. Ko Phi Phi is no longer a secret.” She looked at a group of distant hotels, which were sprawling and several stories high. “Everyone charging more has air-conditioning and satellite television and a swimming pool. Is Patch going to build us a pool?” “We have the beach,” he replied, his thumb moving against her forefinger. “Those big places, not many are on the beach.” “They’re a hundred feet from it.” “A hundred feet too many.” “For you and me, yes. But for someone who lives in Tokyo or Munich? I don’t think so. They walk farther than that just to go to the bathroom.” “It’s better to be closer.” Sarai pushed his sandaled foot with hers, knowing that he would always see their bungalows in the best possible light. While his sentimentality moved her, she wished that he would sometimes observe what she did—that the world was overtaking them. As his foot pushed back against hers, she wondered how she could bring in more money. Lek would try, and he might succeed, but she needed to earn more, whether through the bungalows or her restaurant or something else. Otherwise they would have to leave the island, where almost all of their ancestors were buried, where they went to school and fell in love. They would leave for Bangkok, and the colors of her life would fade. “We have to work harder,” she said. “Somehow we have to work harder.” “I know.” “The children don’t want to move either. We have to work harder for them.” “And we will.” “And you think Patch can make that much of a difference? He’s helping you that much?” “He is making a difference.” A voice emerged from below, the voice of their older daughter. “Then he can stay,” Sarai said, standing up. “For a few more weeks. Until you’ve finished the repairs. But then he has to go. Whatever he’s running from, he’ll have to run somewhere else.” “Three weeks. Give us three weeks.” She put her hand on his shoulder. “Don’t let the children see your worry. I see it. My mother sees it.” “I’ll do better.” “Your face . . . I love it more than my own, but it’s still the face of a child, so easy to read. And Suchin and Niran, they need to hear us laugh and see us smile. That’s what we must always do for them.” Lek grinned, rising slowly, painfully. “So you still see me as a child? After all these years?” “I’ll always see you as a child,” she replied, the corners of her mouth rising, deepening the laugh lines that he so loved. “Why else do you think I married you? For your looks? No. For your money? Definitely not. It’s a good thing for you that I’ve always seen you as a child. Because if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t be here right now. I wouldn’t be thinking about what breakfast you’d like most or about how I’m going to let Patch stay, against my better judgment, because he’ll make your life easier. So thank Buddha for giving you that boyish face. Because without it, your problems would be yours alone. I certainly wouldn’t be sharing them with you.” “Thank you, Buddha.” “Thank him again. A hundred times. If I were you, I’d thank him every day. That way, he won’t decide to change his mind.”# # #

Deep within the midst of his dream, Patch’s instincts told him that the newcomer wasn’t to be trusted. He acted too confident while walking up the stairs that led to the second level. In the backpack slung over his shoulder was supposedly half a kilogram of marijuana—which Patch had already partly paid for, having handed a thick wad of Thai baht to the man’s partner the previous afternoon. This was the local whom Patch trusted. Patch had bought much smaller packs of dope from him on two other occasions, and he’d always been fair, and had restless eyes that seemed to search for police in every nook and cranny. The Thai with whom Patch had dealt, as well as the newcomer, wore trousers, tank tops, and sandals. They weren’t big men, but Patch had seen Thai kickboxers at work against one another and knew size didn’t matter. An elbow or a knee thrown by a trained fighter was much more dangerous than a punch swung by some brute who lifted weights from dawn to dusk. Patch was between the Thais, and when he reached the landing, he turned to the right, toward his room. He tried to slow his pounding heart with the thought of how much money he’d make reselling the dope. The guesthouse was full of foreigners who liked to roll joints but were afraid to buy from the locals. Patch wasn’t. He’d been in Thailand for six weeks and understood who could and couldn’t be trusted. He’d also tried hard to learn a bit of the language, which seemed to put him in everyone’s good graces. The hallway, illuminated by sporadic, naked lightbulbs, stretched far into the distance. The cement floor was blue, the walls pitted and stained. Music, laughter, and the sounds of bodies merging and moving seeped through the wooden doors Patch passed. Reaching into his pocket, he removed a key, thanked the men for meeting him, and approached the brass padlock that secured his room. Inside, the room’s lone window was open, revealing Bangkok’s Khao San Road. One story below, Patch glimpsed the usual assortment of backpackers, vendors, taxis, and chaos before he pulled the curtains shut. Turning around, he saw that the Thai he trusted was locking the door behind him. “Do you want a Coke?” Patch asked, moving toward a battered minirefrigerator that hummed and groaned like a car dying on the roadside. “I’ve also got some beer. The least I can do is buy you a—” “You get money?” the Thai asked in broken English, sweat glistening on his forehead. Patch nodded, wishing that the man didn’t seem so tense. After walking into the bathroom, Patch lifted the porcelain lid of the water tank behind the toilet and pulled out a Ziploc bag containing two thousand baht, roughly sixty dollars. “Do you have the weed?” he replied. He felt cornered in the bathroom, and stepped to the side of his sagging bed. The unfamiliar face smiled, revealing a silver tooth. Suddenly Patch wished the door weren’t locked. He started to repeat his question when his supplier pulled a shiny badge from his pocket. “You make big mistake,” the Thai said as his accomplice removed a small gun from inside his pants, near his crotch. The gun darted toward Patch the way a cobra might strike. Instinctively, he batted it aside, and a bullet thudded into the ceiling. The man shouted in Thai, twisting in Patch’s direction, the gun once again rising and aiming. With Patch’s free hand, he punched the Thai hard in the face, his fist striking the other man’s upper lip and nose. Blood sprayed on the Thai’s tank top and he fell away, dropping the gun. Patch kicked it as the man’s partner rushed forward, his hands open, slamming like small axes into Patch’s shoulders, aiming for his neck. Stumbling backward, Patch could do little to defend himself other than avoid a crippling blow. “You die tonight!” the Thai shouted, his fury more frightening to Patch than the gun. “You die now!” Patch partially warded off a few more blows, felt the window behind him, and leaned back. Suddenly he was falling, spinning, hitting a canopy and tumbling to the ground, landing on his hands and knees. The sidewalk bustled with backpackers, who turned in his direction. The cop put his head out the window and started yelling and pointing. Hands reached for Patch, seeming to claw at him. He beat them away, fueled by his panic and a strength he’d never known. Within seconds he was running, pushing people away, bursting through their outstretched arms. He saw an alley to his right and turned, bounding forward like some sort of animal on the savanna. To his horror, the men who pursued him suddenly metamorphosed into lions. They neared him, their fangs agape, their claws ripping his skin. He heard their snarls, heard the tearing of his flesh. “No!” Patch shouted, leaping out of bed, becoming entangled in his mosquito net as he fell to the floor. The lions and alley disappeared, replaced by the familiar thatch walls of his bungalow. Dripping sweat, Patch lay on the floor, his fists balled, his eyes tearing. He trembled, recalling the dream, a replay of what had actually happened to him five months earlier. He remembered running down the alley, the two thousand baht still in his hand, twisting through a labyrinth of buildings and warehouses until the cries of his pursuers were overcome by the beating of his heart. Patch glanced at the ceiling, worried that he’d pulled the mosquito net from its moorings. Fortunately, he hadn’t. Rising to his knees and then to his feet, he stepped out from under the net and put on a T-shirt and some shorts, feeling a need to get outside. The light of dawn had come and gone, replaced by an amber blanket that seemed to have been draped over Ko Phi Phi. Trying to take deep and measured breaths, Patch moved toward the beach, eyeing his surroundings, grateful that such beauty would help pull him from his misery. Looking to his right, Patch studied the limestone cliff that rose five hundred feet straight above the turquoise bay. The side of the cliff was partly covered in green foliage but was otherwise a slate gray. On the other side of the curving, half-moon beach, about a mile away, a similar cliff soared above the white sand and emerald waters. Between the two wonders of stone, palm trees swayed in a low stretch of connecting land. The sound of miniature waves lapping at the shore was all he heard. Stepping into the warm water, Patch continued to breathe deeply, thinking about his prospects. He’d spent most of his two thousand baht fleeing to Ko Phi Phi. The rest of his money, as well as his passport, credit cards, and clothes, had been left behind with the police. Without his passport, he had no legal way of leaving the country without alerting the authorities. And so he had only two choices—he could turn himself in and be charged with assaulting a police officer and likely spend a year in a Thai prison, or he could try to sneak out of the country. For five months, Patch had been hiding in Ko Phi Phi, trying to formulate a plan. He didn’t want to turn himself in, but escaping Thailand presented a series of problems so severe that thinking about them often sent him hurrying off for a swim. In the water, his problems seemed to flee, at least to an arm’s length away, to a place where they were manageable. During the first few weeks of his time on the island, he’d borrowed money from fellow travelers and kept a low profile. Then he’d been lucky enough to start doing odd jobs for the Thai family who owned a group of dilapidated bungalows at the far end of the beach. In return, they fed him, let him stay in their smallest bungalow, and didn’t ask questions. As long as he kept Lek and Sarai happy, Patch had reasoned, he could stay and develop a plan. He could avoid the police. So he’d worked hard, helping whenever possible, and taking the initiative to fix whatever needed fixing. Mulling over how a coconut had fallen the previous day and damaged a roof, Patch looked up, studying the trees above the bungalows. One tree had a cluster of green coconuts and leaned over the path that ran between all the bungalows and the restaurant. Though made of sand, the path was lined with piles of brown bricks that Lek had asked Patch to use to pave it. Patch wanted to begin work on the path right away, but he worried about the coconuts, which often fell during storms. Afraid that someone would get hurt, he walked toward the tree and was pleased to see that it didn’t rise straight up, but was curved like a giant longbow. Patch had watched local children climb such trees and knew, in theory, how to get from the ground to where the coconuts hung. He put his bare feet on either side of the trunk, reached around the tree as if he were hugging it, and pulled up with his hands while pushing down with his feet. The bark scraped against his thighs and forearms, but he smiled as he lurched higher. His progress reminded him of the inchworms he’d watched as a child. He climbed about as fast, lifting his hands, then feet, hugging the tree. Though his exposed skin continued to get scraped, he climbed until he reached the long, knifelike fronds and the nest of coconuts, about thirty feet off the ground. Holding on to one of the fronds, Patch hoisted himself on top of the tree, resting on the other fronds and the coconuts. “What are you doing up there, you crazy man?” Patch looked down through the fronds and spied Suchin. The daughter of Lek and Sarai, Suchin was eight years old, with a round, pleasing face like her mother’s and long hair that she wore in a braided ponytail. Her hair was pulled far enough back to reveal her pierced ears, which held her first pair of earrings—matching yellow seahorses. She was almost always smiling, seemingly proud of her adult front teeth. Though Patch was used to seeing Suchin in her school uniform, since it was Saturday she wore a faded blue Hello Kitty T-shirt and black shorts. “Be careful, Patch,” she added, moving directly beneath him, her English nearly flawless. “You’ll fall on your head. And you don’t want to do that any more than you already have.” “You be careful. I’m going to drop these coconuts.” “Good. Then Mother can sell their milk.” “Could you please step back?” Suchin did as he asked, watching as he twisted off one of the highest coconuts. Her brother, Niran, appeared, eating a handful of sticky rice. A year younger than Suchin, he had straight black hair and was small for his age. As usual, at least when he wasn’t in school, Niran went shirtless and carried a bamboo pole with a net on one end. “What’s Patch doing?” he asked in Thai, plucking the last few grains of rice from his fingers. “Getting us coconuts.” “For what?” “To sell, silly.” “Oh.” Patch listened to the children talk, made sure that they were a safe distance from the tree, and dropped the first coconut. It landed with a thud, rolled a few feet, and was snatched up by Suchin. “Here comes another one,” Patch said, wrestling with a bigger coconut, surprised by the strength of its bond to the tree. The coconut finally lost the battle and rolled across the sand. Niran hurried forward, then set it next to his sister’s. “Don’t fall, Patch,” he called. Continuing to wrench coconuts free and drop them to the children, Patch worked until only fronds remained below him. Though bleeding in several places, he smiled as Suchin and Niran picked up their prizes and hurried toward the restaurant. He knew that Sarai would set the coconuts in an ice-filled cooler and later chop off their tops, stick a straw in, and sell them for twenty baht each. To Sarai and Lek, coconuts meant that money did grow on trees, and Patch knew they’d be pleased. Wiping his brow, Patch gazed across the bay toward the open sea. To the north sprawled the coast of Myanmar, hardly a country to escape to. More than a thousand miles to the west lay India. Patch was fairly certain that if he reached India, he could find an American embassy, get a new passport, and go home. But traveling to India was another story altogether. He might be able to stow away on a freighter, but that meant going back to Bangkok or maybe the nearby island of Phuket. As he did every day, Patch lamented his stupidity. To make a few hundred dollars, he’d risked everything and turned his dream vacation into the worst nightmare. He was now a fugitive. He’d hurt a police officer. If he were caught he’d be shackled and thrown in prison. Even now, within the haze of relative safety he’d found on Ko Phi Phi, it was hard to forget that his future had been jeopardized by recklessness and naïveté. And tomorrow his brother would arrive and remind him of his foolishness. Ryan would be hard on him, Patch was certain. Ryan would urge him to turn himself in. They would fight and fight and fight, and Ryan would never understand. He wouldn’t understand because he wasn’t a coward, wasn’t afraid to be held accountable. Patch had always thought that Ryan was almost incapable of fear. And Patch doubted that his big brother had ever looked into a mirror and wondered whom he saw. Patch, on the other hand, studied his reflection from time to time, musing over why he sometimes appeared as a stranger to himself. Though the two brothers looked like twins, and were only a year apart, Patch had always walked in the shadow of Ryan’s deeds, sheltered within that shadow but also weary of its influence. This weariness was one of the reasons that when Ryan had returned to business school to finish his master’s degree in management, Patch had traveled in the opposite direction, flying to Bangkok with no plan, with nothing but a backpack full of T-shirts and a yearning for adventure. He was twenty-three years old and brimming with restlessness and optimism. Patch loved his brother as much as anyone else. But he was afraid of what Ryan would say, of the looks that Ryan would give him. Nothing ever seemed to sting as much as Ryan’s disapproval. And Patch had felt it on too many occasions. Wishing that Ryan weren’t drawing so close, Patch stared down the tree trunk, wondering how he would get to the ground. Climbing up had been fairly easy, but going down looked problematic. He might have to jump. As he sat and debated how to approach his descent, Suchin and Niran reappeared. Suchin carried a drink of some sort, saying that it was for him. Niran held an old soccer ball, and asked if Patch would play with him on the beach. Suchin continued to talk as Niran tried to keep the ball in the air with his feet and knees. He wasn’t successful. “You’re stuck like a cat,” Suchin said, giggling. “Though I’ve never seen such a big cat, and I don’t see your tail.” Patch poked his head down through the fronds. “Meow.” The children laughed, Niran dropping the ball. “Come down, sweet little kitten,” Suchin replied. “Mother has a nice bowl of milk for you.” “Meow. Meow.” “Come on. You can do it.” Patch put his feet on the trunk and began to lower himself. He managed to slide about halfway down the trunk before his skin was scraped raw and he jumped away from the pain, and out into empty space, falling toward the children below. # # # Hundreds of miles to the north, Ryan and his girlfriend, Brooke, sat on the balcony of their hotel room, seven stories up and facing the heart of Bangkok. Ryan rested his laptop on his knees. His fingers tapped its keys with relentless speed as he scrolled through emails, replying to professors, potential employers, and friends. Brooke watched him as he typed, thinking that the Thai sun might do him some good. Though she had been attracted to him since the moment she met him in business school, his pale skin seemed out of place here in the tropical heat. The rest of him looked as it often did—his short blond hair spiked upward with gel, his blue eyes covered by narrow sunglasses. As always, he was clean shaven, revealing a strong jaw and prominent cheekbones. His Hawaiian-style shirt was unbuttoned, and the defined muscles of his abdomen appeared as firm as the cement floor of the balcony. Aware that Ryan was engrossed in his work, Brooke shifted her gaze to the city. A dozen towering office buildings reflected the midmorning light. Bangkok’s SkyTrain rumbled above a congested, four-lane road. The blue-and-white train followed the wide curve of the elevated platform, heading toward downtown. The train moved much faster than the thousands of cars, trucks, and motorcycles beneath it. Brake lights made the road seem to glow. Horns were incessant, chirping like the cries of exotic birds migrating en masse. The air smelled of diesel fumes, but also of spices from the restaurant below—scents of saffron and lemongrass and fish sauce. Eyeing the zigzagging paths of scores of traditional three-wheeled taxis known as tuk-tuks, Brooke felt an urge to explore the city. She’d never been outside America and wanted to hop on a tuk-tuk and ask the driver to take them somewhere interesting. “Can’t you finish that later?” she asked, running a hand through her hair, which was light brown with blond highlights and fell well below her shoulders. Ryan glanced up at her, then back at his laptop. “I’m going over Patch’s directions on how to get to Ko . . . Phi Phi, though I can hardly make sense of what he says. Must have been in a hurry.” “It probably costs money for him to get online. And he doesn’t have any.” “So, once again, his problem becomes my problem. Sound familiar?” “We’ve got plenty of time.” “What a freaking mess.” Brooke rolled her green eyes, heard a screech of tires, and watched a SkyTrain approach. “Life is messy, you know. It’s not some perfect business plan that’ll always give you a great return on investment.” “With him it’s messy.” “And what about with me? Waking you up last night?” “That’s different. It’s not your fault.” “But that doesn’t make it any cleaner, Ry.” He sighed, partly closing his laptop. “I need to sweat. They actually have a decent gym downstairs. Would you mind hanging out for an hour?” “We could walk downtown instead of taking a taxi.” “Walking isn’t going to do it. I have to run to work off that nasty airline food. Don’t you?” “No. And I think we’d sweat enough just walking downtown.” Ryan nodded, noticing how her skin glistened. She wore a blue Mickey Mouse T-shirt, white shorts, and flip-flops. Her legs were mostly exposed, and his eyes followed the contours of her calves. She was more curves than muscles, more soft than not. Her breasts seemed to push at her T-shirt, and he had a sudden desire to lift Mickey above her head, to kiss her flesh. Her eyes found his and he smiled. “Caught me, didn’t you?” he asked. “I always catch you.” “Usually. Usually, but not always.” “You’re not as sly as you think. Unrelenting, yes. But sly, no.” “Can you blame me for trying?” Brooke nodded, though sometimes she wished he didn’t try. He forgot that men could try too hard with her, that men had tried too hard with her. “Go on,” she said. “Go work off that nasty food. I’ll be here for an hour. After that, you’ll have to go looking for me.” He set aside his laptop, putting his hand on her knee. “I’ll explore downtown with you. I promise. I’ll do a few reps, hit the treadmill, and head straight back.” “You could run in the city.” “In all that pollution? No way.” She glanced at the endless cars. “Maybe you should talk to them about sustainability. Put some of your thoughts to the test.” “Maybe I should.” He stood up, moving with purpose, as always. “We’ll explore, see some sights, have lunch, do whatever you want. And then maybe we can come back and I can get a look at what’s hiding behind Mickey.” “Really, you should study this place. It might teach you something.” He pulled off his shirt, grabbed his iPod, and then walked into their room. She watched him change into his workout clothes, wondering why the sight of his nakedness didn’t stir her as it once had. He could have modeled for a famous sculptor, she thought, recalling images of white marble statues that she’d seen in some history book. After saying good-bye, she returned to the view of the city. She should have taken the time to use his laptop to catch up on her studies as well. Though her specialization in business school was marketing, while he studied management, they were in two of the same classes, and he was wise to use the holiday break to get ahead of everyone else. But she didn’t want to read about IPOs or exit strategies or venture capital. She wanted to watch Bangkok—a chaotic, mesmerizing city that seemed to inspire something within her, something that had been robbed of wings but still longed to take flight. # # # As usual, midday on Ko Phi Phi brought heat, humidity, and sun. The island lay near the equator and at times felt like the inside of a greenhouse. The scent of damp soil mingled with that of tropical flowers and salt-laden air. The water near Rainbow Resort was placid, as it was in all but the strongest of storms. Most of the bay was protected by the limestone cliffs, which curved inward from the north and south, forming a shield the shape of a half-moon. The water was such a bright blue that it almost appeared to be illuminated from below. Though Rainbow Resort wasn’t popular among tourists, its beach was a desirable destination, and held a few dozen wooden lounge chairs, half as many faded Heineken umbrellas, and travelers from around the world. Swedes, Danes, Germans, Brits, Israelis, Japanese, and Australians lounged in the chairs, kicked soccer balls on the beach, or waded in the shallows. Most of the tourists were in their early twenties, some sunburned, others tanned. A trio of Swedish women sat in the bay, fifty feet from shore, the water almost reaching their exposed breasts. Farther out, several Westerners used snorkels and masks to explore beneath the tranquil surface. As they often did during the weekend, Suchin and Niran walked along the curving row of chairs and umbrellas, asking foreigners if they needed cold drinks or ice-cream cones. If anyone did, one of the children would ask for thirty or forty baht, walk to the restaurant, and give their mother the money in exchange for the treat. Sometimes Suchin carried her little sister, Achara, on her back, but when the weather was hot, Achara was usually looked after by her grandmother in the restaurant. Today Suchin and Niran were alone. They didn’t enjoy some chores, such as cleaning up the beach in the morning or at dusk, but chatting with foreigners had never bothered them. Suchin, in particular, liked selling refreshments, liked the smile on her mother’s face when a sale was completed. Since the sky was cloudless, business was brisk, and the siblings walked from one end of the chairs to the other several times before deciding that everyone was content. Niran knew that the afternoon ferry would soon dock on the opposite side of the island and that his father would want him to help lure customers to their resort. Worried that he wouldn’t have time to play, he took Suchin’s hand and led her toward the water. “Let’s catch some crabs,” he said, wondering where he’d left his net and digging spoon. “You and your crabs. And your fish. There’s no room left in your tank. The fish practically sleep on each other.” “Fish don’t sleep.” “Well, your fish are going to sleep forever if you put any more in that tank.” “Maybe we can . . .” Niran paused as his father appeared in the distance, wearing a frayed canvas hat that a tourist had given him years earlier. “See, we should have worked faster,” Niran said. “Now I have to go to the pier.” “I’ll go to the pier. You stay with Achara.” “No, no, no.” “Wait. Let me tell you a new joke before you go.” He watched a fish break the surface of the nearby water. “Tell me.” “Why did the farmer call his pig Ink?” “Why?” “Because he kept running out of the pen.” Niran giggled, pushing her. “Tell me another one.” “What’s skinny, has black hair, and says ‘ouch’?” “I don’t know.” She reached forward, pinching his arm. “Ouch!” “It’s you,” she said, giggling. “You’re the answer.” Before he could get revenge, she kicked some sand at his feet, and then ran toward their restaurant, waving to her father but not pausing. Niran started to run after her but stopped, since she was much quicker. He saw that his father was carrying their sign—a piece of wood that had been painted white, with RAINBOW RESORT written in bright colors. “You sold six Fantas, four Sprites, and three beers?” his father asked, leading him to a footpath behind the beach, limping as he walked. “And one of Patch’s coconuts.” Lek smiled, though he wished they had sold more. “You’re a fine salesman. Are you sure you want to be a scientist?” “Of course I’m sure. Then I can catch all the fish I want. Just like the French scientists who were tagging all those tuna.” “That was neat.” “It was amazing. And they get to do it every day.” “How about we tag some tourists today? We’ve got seven empty bungalows. And that’s seven too many.” “Let’s try.” Father and son followed the path, which turned to the east, toward the interior of the butterfly-shaped island. The body of the butterfly was a rise about a mile long and a half mile across. On either side lay a beach, and at the end of each beach rose the massive limestone cliffs. The main village was located between the beaches. As they neared the village, they began to pass a row of simple one-story shops that sold T-shirts, swimsuits, balls, sunscreen, refreshments, souvenirs, jewelry, and just about anything else that a tourist might want. The farther they walked, the more elaborate the stores became—soon small, A-framed structures that mimicked traditional Thai architecture. These one- or two-room stores contained masseuses, dive centers, Internet cafés, crepe and pastry shops, minimarts, and travel agencies. The walkway was now paved with bricks, and thinking about how Patch had started to work on their path, Lek smiled. He looked up, gazing at the main trunk of a massive banyan tree that dwarfed everything beneath it. The base of the tree was encircled with strips of red, blue, white, and yellow fabric. A little red shrine had been inset within the weblike mesh of the tree’s roots. Several incense sticks burned near the shrine. A variety of soft drinks had been set nearby—opened, but not emptied. Straws were aimed skyward, offering ancestors easy access to the drinks. The center of the village bustled with vendors, children, and tourists. The foreigners wandered around carrying large backpacks, sat in cafés, haggled with shopkeepers, or studied maps and guidebooks. As Lek and Niran approached the opposite beach, a slew of restaurants materialized. Each restaurant had some sort of wooden boat outside, which was filled with ice and fresh seafood. There were rows of squid, giant prawns, lobsters, crabs, clams, snapper, shark, barracuda, and sea bass. Patrons could order any item and have it cooked to their specifications. Lek studied the offerings, wondering what he and Niran would spear for dinner. He didn’t see much tuna and decided to hunt for such a fish. More tourists might come to their restaurant if fresh tuna was available. The pier was about three hundred feet long and filled with people, carts, and baggage. Secured to the pier near the shallower waters were almost a dozen colorful dive boats, full of glistening scuba tanks and grinning tourists. Next came several rust-stained barges that had brought goods from Phuket. Toward the end of the pier, battered two-story passenger ferries had been lashed together, so that they pointed toward shore and stretched out, parallel to the pier. The boats were empty, but in the distance a white-and-blue ferry approached. Dozens of Thais congregated near the end of the pier, holding signs and brochures featuring their guesthouses and resorts. Lek greeted many of the men and women he saw, taking his place in line. None of them jostled for a better position or sought to create a competitive advantage. Everyone was friendly, excited by the prospect of a full boat, of travelers with money to spend. Lek leaned against a steel railing, his hip aching. “What did you learn in school yesterday?” he asked his son. “What?” “Tell me, my little daydreamer, what you learned in school yesterday.” Niran shook his head. “Nothing.” “Nothing? That can’t be true. Think of one thing. One thing to make your father smarter.” “Well, a whale is not a fish. It breathes air. Like us. I asked Miss Wattana about whales. And she told me all about them.” “Really?” “A whale has a . . . a hole in the top of its head. And it goes to the surface and breathes air.” “Hmm. I didn’t know that. Thanks for making me smarter. Your mother would be proud.” Niran scratched at a mosquito bite. “Some whales can hold their breath for more than an hour.” “Really?” “They dive down so deep, and look for squid to eat. And they sing to each other while they hunt.” “How wonderful. What kind of songs do they sing?” “Long, moaning songs,” Niran answered, still scratching. “I want to hear one someday.” “Keep studying, so that when you hear one, you’ll know just what it means.” “I will.” Lek pointed to the approaching ferry. “It’s about ready to dock. And we need to fill up those seven bungalows. What do you think, should we drop our price?” “To four hundred baht a night?” “Let’s try three seventy-five.” “All right.” “Will you give it your best, my son? Let’s really try to reel them in.” Niran nodded, watching the ferry pull alongside an almost identical vessel at the end of the row. A few minutes passed before tourists started crossing from boat to boat, drawing nearer to the pier. Most of the newcomers spoke excitedly and eyed their surroundings. All carried large backpacks. As the foreigners approached, the Thais began to hold up their signs and, in broken English, encourage people to come to their guesthouses. Since Niran’s English was much better than his father’s, when he wasn’t in school he often visited the pier and tried to entice people to come to Rainbow Resort. Sometimes Suchin joined them as well. Lek realized that the boat was less full than he had hoped—which was unfortunate, because the nicer resorts would continue to have vacancies. He listened to his competitors, aware that many were also dropping their prices. After whispering to Niran to offer three hundred and fifty baht for a room, he gripped his fists tight as his son exchanged words with a group of blond-haired women. He thought that they were going to agree to Niran’s offer, but in the end, one of the women thanked him, patted him on the head, and turned away. Lek closed his eyes, angry that the woman had touched Niran’s head, that she didn’t know Thais considered heads to be sacred and therefore practically untouchable. Niran knew that his father was watching him, that his family depended on him. And so he smiled wide and used his best English. He told tourists about the beauty of Rainbow Resort, about how his mother was the number one cook on the island, and about how their bungalows were on the prettiest part of the beach. But many tourists already had reservations at nicer places, and Niran didn’t have brochures like some of the other people offering places to stay. All he had was his voice, which he used as a poet uses words. He made people slow with his voice; he made them stop and smile. But even when he dropped the price to three hundred baht, people kept shaking their heads. And soon only a smattering of Thais remained on the pier. Having failed his father, Niran turned and walked toward shore, watching his bare feet rise and fall. “I’m sorry,” he whispered, switching to Thai. Lek paused and, despite the pain in his hip, bent down to look into his son’s eyes. “Don’t be sorry. You tried your best. And you spoke so well. I’ve never heard you speak so well.” “Why didn’t anyone come?” “Because there are too many of us and too few of them.” “I wasn’t good enough. Suchin would have been better.” Lek smiled. “You were perfect. Just perfect. Now let’s go get the spear gun and catch a tuna. So many of these foreigners like sushi. Let’s hit a tuna and fill their bellies with it.” “Tuna are hard to hit. They can swim up to almost a hundred kilometers an hour. Faster than cars.” “So that’s why we usually miss them? Because they’re faster than cars?” “That’s right. That’s why it’s so hard to bring one home.” Pursing his lips, Lek pretended to ponder Niran’s words. “Well . . . don’t you think it’s hard for air to find the hole in the head of a giant whale?” “That would be hard.” “But the air finds the hole. Every day. And so maybe today we’ll find a tuna. Such a big tuna that we can eat some after the foreigners are full.” Niran scratched at his bare, bony shoulder. “Let’s go.” After slowly straightening, Lek turned to look at the ferry, wishing that it had been full. Sarai would be disappointed once again. “Let’s surprise your mother with the biggest tuna she’s ever seen,” Lek said, increasing his pace, grimacing at a sudden bout of pain. “Does your hip hurt?” “No. Not today. So let’s hurry, my little scientist. Let’s hurry and make her happy.” # # # Several hours later, on the sandy area behind Rainbow Resort, a group of about fifteen Thai children played soccer. Only two girls competed, each on opposite teams, wearing shorts and T-shirts, while the boys wore only shorts. The field, about forty feet wide and seventy feet long, had been cleared of palm trees by Lek a decade earlier, before he hurt his hip. He’d wanted his future children to be able to run, as he had fond memories of doing so as a boy. And though he’d been tempted to build bungalows on the field, he’d been able to resist this notion, convincing himself that foreigners wouldn’t want to be so far from the beach. His neighbors had encouraged him as well, glad that their children had a place dedicated to the game they loved. So much of the island was devoted to tourists. Foreigners stayed on the nicest stretches of sand, scuba dived above untouched reefs, and enjoyed the best of everything. Most of the locals lived far from the beaches and worked all hours of the day. Lek might have been able to earn a bit more money by destroying the soccer field, but he chose not to. And his wife, who was practical in many ways, and who deftly managed what little money they possessed, wanted the field to remain as it was. Sarai liked hearing the children laugh after school as she diced vegetables with her mother and prepared to feed ten or twenty people. Now, as Lek leaned against the back of the restaurant and watched his daughter and son with pride, he wondered what would happen to the field if they were forced to leave for Bangkok. Surely it would be developed—guesthouses or a hotel put in its place. Suchin’s and Niran’s friends would have to find another place to play. And while several such fields existed in the middle of the island, they were closer to piles of discarded water bottles and old engines than to any beach. Suchin had always been much better at soccer than Niran. She could defend, pass, and dribble as if she’d learned such skills in the womb. Niran often looked as if he’d just started to play. To his friends’ surprise, he didn’t seem to mind being one of the worst players. Though no one else knew why, the reason was simple—Niran saw his father hobble every day and he felt no need to be the fastest or strongest. His being so fast might make his father sad. From inside the restaurant, Lek heard Sarai announce that dinner was ready. He started to call out to his children but saw that Niran had the ball and was dribbling toward the goal. “Hurry,” Lek whispered, clenching his fists, releasing the tension when another boy kicked the ball away from Niran as other defenders cheered. “Mother’s waiting,” Lek interjected, stepping toward the game. Suchin passed the ball to one of her teammates, waved good-bye, and turned toward her father. Niran started to do the same but saw that a small hermit crab had wandered onto the field. He bent down, picked it up, and hurried toward the restaurant, placing the crab near the corner of the structure. Lek complimented his children on the game, smiling as he followed them toward the kitchen. Set in the back of the restaurant, the kitchen was a cinder-block room about five paces long and three paces wide. Much of the room was dominated by full-length, stainless-steel countertops. Piles of diced onions, tomatoes, garlic cloves, lemongrass, mushrooms, and baby corn occupied one area, as did a mound of fresh shrimp, and a large barracuda that Lek and Niran had killed with their spear gun. In the back of the room, a four-burner gas stove held a wok and a large pot. Sitting in the corner of the room was the children’s grandmother, whom they called Yai. Achara, naked and wide-eyed, lay between Yai’s thighs. Yai seemed as large as Achara appeared small. Dressed in a loose-fitting purple sarong and a white cotton blouse, Yai leaned back in her chair and smiled at the sight of Suchin and Niran. “Did you brush yourselves off?” she asked. “Your mother can’t have two specks of sand in her kitchen. One might be fine, but definitely not two.” Suchin glanced at her grandmother’s wide and full face, surprised that her gray hair was peeking from beneath the red cloth that she liked to wrap around the top of her head. “I shook myself clean; I promise.” “Like a dog after a bath?” “I did.” “And you, Niran?” “What?” “Did you do some good shaking?” Niran had been thinking of a shark he’d seen when they were trying to find a tuna and, without answering his grandmother, stepped back outside and brushed the sand from his feet, knees, and elbows. He reentered the kitchen and saw that his mother was adding noodles, vegetables, and slices of pineapple to a long-handled wok, which sizzled above a strong fire. As he often did when in the kitchen with the women, Niran leaned against the far wall, watching. He would have been happy to slice up the barracuda or to help in some way, but no one cooked except his mother, which was how she liked it. Bending over, Suchin picked up her baby sister, holding her casually, burping her without thought. Suchin’s hands pressed against Achara’s naked bottom and back, keeping Achara firmly positioned against her own belly and chest. She wished her father and brother had caught a tuna or a lobster, knowing that her mother would flavor their meal with pieces of the bony and bland barracuda. “How was your day?” her mother asked, holding the handle of the sizzling wok, flipping the ingredients with a toss of her wrist. “We sold fourteen drinks,” Suchin answered, continuing to pat her sister’s back. “I know. A very impressive number.” Yai rose slowly from her chair, moving to a cutting board. “You’ve done well, Suchin. But I’ll tell you what’s even more impressive.” “What?” “Try watching your mother run around like a headless chicken all day. Now, that’s impressive.” Turning down the heat beneath the wok, Sarai rolled her eyes. “Impressive is how that body of yours continues to get bigger. Day after day after day.” “I like being fat,” Yai replied. “It’s my excuse for not working.” “What was your excuse ten years ago?” “You.” “Me?” “That’s right. Watching you move so fast made me tired. Just like it does today.” Sarai began to dish up plates of steaming food for her children. “I didn’t know that someone could sit for so long. Doesn’t your bottom hurt?” “Oh, it’s nothing that—” “Or maybe that’s why you like all that padding. So you can sit in comfort, no matter where you go.” “Padding is good. Nothing wrong with having a built-in cushion.” Suchin grinned as her mother and grandmother continued to tease each other, as they often did. She followed her mother out into the restaurant and sat down at a table in the corner. Niran sat across from her, the small hermit crab in his hands once again. He set the crab on the floor, aiming it toward the nearby railing and beach. Dinner was vegetables, pineapple, and barracuda flavored with a sweet-and-sour sauce. A mound of steamed white rice also rose on the children’s plates. Niran began to eat, pleased to see Patch in the opposite corner, waiting patiently for his food. Patch ate whatever the children ate—rarely shrimp or tuna, but plenty of delicious food. Niran smiled when Patch waved, then turned back to his food, wanting to finish it before the hermit crab escaped. A few minutes passed and then a group of four Italian tourists walked to one of the low outdoor tables on the beach, dropping down on the colorful tapestry spread under the table, stretching out and talking loudly. Patch watched the young men with interest, as they had been renting two bungalows for several days now, and often were noisy and borderline obnoxious. He was amazed at how many Singha beers they could consume in a night, bottles gathering around them like spent artillery shells. Sarai placed Patch’s dinner in front of him, and he put his hands together, bowing slightly. He thanked her in Thai, adding in English that her meal looked delicious. “I so excited for your path,” she answered, grinning, her English less refined than her children’s. “Thanks. I think it will be nice.” “You are nice, Patch. Nicer than my food.” “No way. Impossible.” She laughed, stepping away from him and toward the Italians, who were calling out for more beer. Patch watched her hurry toward them, as if their order might disappear if her feet didn’t move fast enough. He wondered what Niran and Suchin thought of their mother so quickly rushing to meet the needs of foreigners—probably nothing, having witnessed such scenes since birth. Sarai took the order, then walked behind the bar and removed four oversize Singha bottles from an old-fashioned, tablelike refrigerator. Patch watched her, then picked up his spoon and began to eat. As usual, the food was fresh, light, and delicious. He’d smashed his thumb laying a brick, so using the spoon required patience. Eating slowly, he thought about what his brother might be doing in Bangkok. He had been surprised to learn that Ryan was planning to bring his girlfriend, Brooke, whom Patch didn’t know. She’d met their parents only once. Though Patch was a year younger than Ryan, he had more experience with women, was more interested in them. Sports and academics had always come first for Ryan, while women often seemed an afterthought. Patch saw the world from the opposite perspective. To him, relationships were his prize possessions, and forming them was his chief aim in life. Good grades, career success, and other such achievements were of secondary importance. One of the Italians belched, and Patch glanced in the group’s direction. The sand near their table was already littered with beer bottles. To the west, the setting sun illuminated the bay with the colors of a campfire. The bay was almost empty. Most travelers had left the beach, though a few still swam and tossed a Frisbee. The beauty surrounding him made Patch think about the inside of a jail cell. He’d waste away in such a place. Though Ryan would certainly be able to endure a year in a Thai prison, Patch knew that he couldn’t. The loneliness of such an existence would suffocate him, as would the knowledge of the humiliation that he’d brought upon his family. Better to roll the dice and gamble on a voyage to India, as outlandish as it seemed. It would be far better for his parents if he stowed away on a ship for a few weeks than if the local newspaper wrote stories about his imprisonment in Thailand. The Italians called again to Sarai, who appeared in less than a minute. Patch saw her quickly assess the mess that her guests had created. The turquoise tapestry, which he knew she had carefully washed and ironed, was covered with sand. The flowers she’d set in a small vase had been dumped out so that the vase could accommodate cigarette butts. Patch saw Sarai smile and nod, and he was suddenly aware of her predicament, of how she wouldn’t want her children to see drunk tourists or her efforts to set a pretty table defiled. Yet she had to please her guests, regardless of her dignity. After finishing his meal, Patch said good night to Suchin and Niran. He left the indoor part of the restaurant and walked toward the beach, kneeling on the sand when he arrived at the Italians’ table. “Hi,” he said, his hands on his thighs. The smallest of the foursome, who had curly, shoulder-length black hair, nodded. “Hello.” “Do you mind if I have a smoke?” The Italian pulled a cigarette from a pack, passing it and a lighter to Patch. “Enjoy.” Patch lit the cigarette, pretending to smoke. “Thanks a lot.” “Okay.” After starting to rise, Patch paused. “Would you do me a favor?” “What?” “The woman who keeps bringing you beer. Her name is Sarai. Could you thank her next time? She works really hard. And it would be nice if you thanked her.” The Italians looked at one another. Their smiles faded, and their bottles remained on the table. Patch thought that they might stand to argue with him. His heartbeat quickened. His cigarette trembled. But instead of rising, a large, bearded Italian nodded. “You are the one who was working on . . . the path?” he asked, his English slow and tentative. “Yeah. That’s me.” “You work for her?” “Just a few odd jobs.” The stranger took a deep drag on his cigarette. “We will thank her.” Patch nodded. “Enjoy your night.” Grunting, the Italian turned away. Still pretending to smoke, Patch started to walk to the beach but remembered the children. Glancing at his cigarette, he headed back into the restaurant and approached their table. He smiled, leaning toward them. “I don’t smoke,” he whispered. “But I had to pretend for a bit. Okay?” Suchin moved closer to him. “Why are you pretending?” “I . . . I had to make some friends.” “With those boys?” “That’s right. So don’t ever smoke, all right?” Niran pushed his empty plate aside. “Can you swim with us tomorrow?” “Sure. Maybe before my brother gets here.” “Will you introduce us to him?” Suchin asked. “Of course.” “Good. We want to meet your big brother.” Patch smiled. “You do? Why?” “Because he’s part of your family,” she replied, toying with one of her earrings. “He’s part of you.” “And we like you,” Niran added. Suchin let go of her earring. “Want to hear a joke?” “Sure.” “It’s a long one.” “I like your long ones.” “A young turtle was at the bottom of a tall tree. He was tired. So tired. But he took a deep breath and started to climb. About an hour later, he reached a high branch and crawled along to the end. He turned and spread all four flippers and jumped off the branch.” Suchin paused, pretending to be a leaping turtle. “After landing at the bottom in a pile of soft sand, he shook himself off, crawled back to the bottom of the tree, took another deep breath, and started to climb. Watching him from the end of another branch were a mother and father bird. The mother bird then turned to the father bird and whispered, ‘Maybe it’s time we told him that he’s adopted.’” Patch laughed with the children, having heard many of Suchin’s jokes, and always happy to do so. He complimented her, glancing across the bay. The sun had just set, and the water was awash with color. “How about a quick swim right now? Want to ask your mother?” Niran hurried from the table. Suchin took Patch’s cigarette and stubbed it out on her plate. “Don’t let my mother see you with that. Even though you’re my American brother, she’d still be angry at you. And believe me, you’d rather have a hive of bees angry at you.” “I believe you.” Suchin picked apart the cigarette butt, then put the remnants on her plate and covered them with some sweet-and-sour sauce. She took Patch’s hand, squeezing it tight. “Let’s see what she told Niran. I hope she said yes.” “Me too, Suchin. Me too.”

Discussion Questions

1. Where were you when the Indian Ocean Tsunami struck on December 26, 2004?2. What was your reaction to the catastrophe?

3. Some novelists tend to stay away from subject matter that evokes such powerful emotions. Did John Shors bring the story of the disaster to life in a way that honored those who died and suffered?

4. The author traveled multiple times to Ko Phi Phi before and after the tsunami struck. Do you think it’s important for writers to have such personal connections with the places they bring to life on the page?

5. Cross Currents explores the relationships between locals and tourists. In real life, do you think each set of people understands the other?

6. How do you believe people from different cultures best learn from each other?

7. What did you think of Patch’s initial decision to try to flee Thailand, rather than to turn himself in? If you had been related to him, would you have tried to convince him to take another path?

8. Lek and Sarai assume a significant amount of risk when they let Patch stay with them for such an extended period of time. Did you agree with their decision?

9. What did you think about the relationship between Ryan and Dao? What was each character looking for?

10. Which character faced the greatest challenges and rose to the occasion most impressively?

11. If you had lived on Ko Phi Phi and endured the tsunami, would you have left afterwards?

12. What do you think about the book’s title? Did your perception or feelings toward the title change after reading the novel?

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

On December 26, 2004, one of the largest earthquakes in human history occurred off the coast of Indonesia, creating a series of massive tsunamis that struck countries bordering the Indian Ocean. Waves varied in height, some reaching almost one hundred feet tall. It is estimated that 230,000 people, representing forty nationalities, died in the catastrophe. Ko Phi Phi is a beautiful, butterfly-shaped island off the coast of Thailand—an island that has long been a prized destination for tourists. The center of Ko Phi Phi, where people live and work, is about six feet above sea level. Two waves struck Ko Phi Phi—each from an opposite side of the island. One wave was ten feet high, the other eighteen. The waves met in the middle of the island, pulling restaurants, hotels, schools, and people out to sea. Approximately one-third of Ko Phi Phi’s ten thousand residents and visitors died. Yet, miraculously, thousands of Thais and tourists lived. Cross Currents is inspired by my multiple trips to Ko Phi Phi, before and after the tsunami. It’s a fictionalized account of this calamity—of what happened, and of the tragedies and triumphs of that day…”Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more