BKMT READING GUIDES

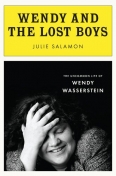

Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein

by Julie Salamon

Hardcover : 480 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

In Wendy and the Lost Boys bestselling author Julie Salamon explores the life of playwright Wendy Wasserstein's most expertly crafted character: herself. The first woman playwright to win a Tony Award, ...

Introduction

The authorized biography of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein.

In Wendy and the Lost Boys bestselling author Julie Salamon explores the life of playwright Wendy Wasserstein's most expertly crafted character: herself. The first woman playwright to win a Tony Award, Wendy Wasserstein was a Broadway titan. But with her high- pitched giggle and unkempt curls, she projected an image of warmth and familiarity. Everyone knew Wendy Wasserstein. Or thought they did.

Born on October 18, 1950, in Brooklyn, New York, to Polish Jewish immigrant parents, Wendy was the youngest of Lola and Morris Wasserstein's five children. Lola had big dreams for her children. They didn't disappoint: Sandra, Wendy's glamorous sister, became a high- ranking corporate executive at a time when Fortune 500 companies were an impenetrable boys club. Their brother Bruce became a billionaire superstar of the investment banking world. Yet behind the family's remarkable success was a fiercely guarded world of private tragedies.

Wendy perfected the family art of secrecy while cultivating a densely populated inner circle. Her friends included theater elite such as playwright Christopher Durang, Lincoln Center Artistic Director André Bishop, former New York Times theater critic Frank Rich, and countless others.

And still almost no one knew that Wendy was pregnant when, at age forty-eight, she was rushed to Mount Sinai Hospital to deliver Lucy Jane three months premature. The paternity of her daughter remains a mystery. At the time of Wendy's tragically early death less than six years later, very few were aware that she was gravely ill. The cherished confidante to so many, Wendy privately endured her greatest heartbreaks alone.

In Wendy and the Lost Boys, Salamon assembles the fractured pieces, revealing Wendy in full. Though she lived an uncommon life, she spoke to a generation of women during an era of vast change. Revisiting Wendy's works-The Heidi Chronicles and others-we see Wendy in the free space of the theater, where her many selves all found voice. Here Wendy spoke in the most intimate of terms about everything that matters most: family and love, dreams and devastation. And that is the Wendy of Neverland, the Wendy who will never grow old.

An Interview with Julie Salamon, author of the new book, Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein.

Q: Why did you title the book Wendy and the Lost Boys?

Julie Salamon: As the research progressed, I noticed that the classic story, Peter Pan, became a recurrent motif. Wendy was one of the many Baby Boom babies named for Wendy Darling, Peter's beloved friend, after the book became a popular Broadway musical starring Mary Martin. Wendy performed in the play as a girl, choreographed a dance for an avant-garde version in college, and named her daughter Lucy Jane (Jane was the name chosen by Peter's Wendy for her little girl). For Wendy's peers, Peter Pan became emblematic of a generation that tried to retain eternal youth, and then had to contend with the realities of aging and responsibility.

Moreover, Wendy's life was filled with ?lost boys,? including a brother who was mentally disabled (and who was pretty much dropped from conversation within the family and who was separated from the family at an early age). Her ?lost boys? included the gay men of the theater who became her closest circle, even as they all lived through vast changes in their lives and personal relationships.

Q: Wendy came from an extremely successful family; can you describe what shaped her as a young girl growing up?

Salamon: Wendy was born in 1950, to immigrant parents, just five years after the end of World War II; her family was caught up in the postwar desire to achieve the success that would make them safe. Her mother Lola, in particular, had a fierce personality and powerful ambition. Lola instilled the paradox that would become a recurrent theme in Wendy's life and her work, the feeling of being better than everyone else but also not quite good enough. In The Heidi Chronicles, Wendy refers to the phenomenon of being 'superior-inferior.?The playwright was also profoundly shaped by the times she lived in. In her youth, the 60s roared through New York, calling everything into question. The world was changing fast, creating a charged and exciting atmosphere of provocation and creativity: Civil rights, pop art, the Beatles, feminism, pacifism and protest. It was a pivotal moment, the line of demarcation between conformity and rebellion, stability and chaos.

Q: Wendy's story reflects the accomplishments--as well as the fear and anxiety--of women who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s. How was she affected by the changing roles and attitudes of women, and how did her work reflect those changes?

Salamon: Her work--plays, essays and a final novel--reflected her life and her life reflected the times she lived in. Uncommon Women and Others deals with the youthful dreams of young women who came of age as society's demands and expectations were undergoing a vast transformation. In subsequent plays, notably Isn?t It Romantic and The Heidi Chronicles, she dealt with the complex choices women confronted as they faced competing desires for home and family and successful careers. In essays dealing with her family and her decision to have a baby as a single mother, she acknowledged the longing for home, while struggling to find her place in society that hadn?t found a way to satisfy competing desire. Her final play, Third, contends with the disillusionment and reflection of a woman in middle age, contending with children, career, and aging parents.

Q: You characterize Wendy as at once extremely social and yet mystifyingly private--can you elaborate?

Salamon: After Wendy died, her close friend, the former New York Times columnist Frank Rich, wrote, ?How could the most public artist in New York keep so much locked up? I don?t think I was the only friend who felt I had somehow failed to see Wendy whole.? She gave the illusion, in her writing and in her relationships, that she made her life an open book. It was only after she died that people began to realize how much she kept hidden.

As with so much in her life, the source of her secrecy was her mother. Lola Wasserstein suffered many losses, and survived by forging ahead, not ?dwelling? on past wounds. The family joked that, when people died, it was said ?They went to Europe.? Wendy's reaction to her upbringing was to hide in plain sight--giving the illusion of revelation, while keeping the most crucial information locked inside.

Q: Your portrait of Wendy reveals a remarkable driven yet remarkably insecure woman--what do you think accounts for that insecurity?

Salamon: One of Wendy's friends once said: ?Wendy was a very driven person, and yet she was a very warm person. Sometimes those things came into conflict.? Much of her insecurity derived from the ambition that led her into the highly competitive world of theater. The ?vicious dumpling? as one friend called her, wasn?t really very vicious but she had inherited her mother's urge for self-preservation. Balancing her wish to be loved with her lofty goals was a high wire act.

A more profound source of her insecurity was the absence of her mentally-disabled brother Abner, who she didn?t meet until she was almost fifty years old. The family's secrecy about him and other matters kept Wendy off-balance, unable to fully trust her own sense of reality.

And then there was Lola, always quick to remind her daughter that she wasn?t svelte enough, she wasn?t married, and she didn?t have children (until late in the game). Wendy often told the story of Lola's response to her daughter winning the Pulitzer Prize: ?I?d be just as happy if she brought home a husband.?

Q: Bruce Wasserstein was a famous character in his own right, a Wall Street titan--what was her relationship with her brother?

Salamon: While I was working on the book, a Wall Street guy cornered me at a party and said: ?I want you to find out how the same DNA produced Bruce and Wendy.? This was a frequent refrain. He became a billionaire, known as a pugnacious investment banker with little regard for social (or business) niceties. She was beloved as both playwright and person, considered a best friend even by people who barely knew her. Yet they were more alike than different in their ambition, their willingness to disregard convention, their extreme desire for privacy. They were very close, though their separate orbits often led to fractiousness. ?I can?t help wondering whether what I say has any relevance for him at all,? she once wrote. In the end, though, when she was dying, Wendy turned to her brother and his wife to care for Lucy Jane.

Q: What drove Wendy, at age 48, to give birth to her daughter, and how did motherhood affect her?

Salamon: Throughout her life Wendy expressed yearning for a family. In a little-known play called "Miami," about her childhood, the adolescent character based on Wendy discusses the conflict she feels, between wanting to be a star and wanting children. She was quite close to her nieces and nephews and discussed having children with various men in her life. On the other hand, her actions often contradicted this desire. She repeatedly fell in love with unavailable men, many of them gay. For years she underwent in-vitro fertilization, but never engaged wholeheartedly in the process. By the time her daughter was born, Wendy was 48 years-old and already showing signs of the illness that eventually killed her. Much as she loved Lucy Jane, Wendy was often too ill or too preoccupied with her writing to enjoy being a mother as much as she had hoped.

Q: What was the theatrical scene like in the 70s and 80s when Wendy came of age as a playwright?

Salamon: Wendy came of age as a playwright as the nonprofit theater world hugely expanded. She became one of the original group of playwrights at Playwrights Horizons who brought a Baby Boom mentality to theater, and help create a sense of excitement and relevance for a new generation of theater-goers. In telling Wendy's story, Wendy and the Lost Boys also recalls the formative years of Wendy's group, which included James Lapine, Stephen Sondheim's longtime collaborator; Andre Bishop, who became artistic director of Lincoln Center after putting Playwrights Horizons on the map; playwrights Christopher Durang and William Finn. Frank Rich, then the New York Times drama critic (and who became known as the Butcher of Broadway) was a dear friend of Wendy, a friendship often looked at with raised eyebrows by her theater friends, many of whom were on the receiving end of Rich's lacerating prose.

Q: What do you think her legacy will be in the theater? Will her plays pass the test of time?

Salamon: Her plays were, in many ways, bright sociological commentaries on her times, though "Uncommon Women and Others," and "The Sisters Rosensweig," contain enduring themes about friendship and families. Certainly her success as a woman playwright continues to be an inspiration, considering how much less notably women have progressed in the theater world compared with other professions, including the arts.

Julie Salamon is available for further interviews. Please contact: Elisabeth Calamari at 212-366-2857 or [email protected].

(Photo of Julie Salamon © Sara Krulwich)

Discussion Questions

No discussion questions at this time.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more