BKMT READING GUIDES

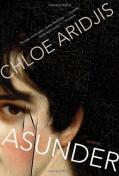

Asunder

by Chloe Aridjis

Paperback : 208 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Marie's job as a guard at the National Gallery in London offers her the life she always wanted, one of invisibility and quiet contemplation. But amid the hushed corridors of the Gallery surge currents of history and violence, paintings whose power belies their own fragility. There also lingers the legacy of her great-grandfather Ted, the museum guard who slipped and fell moments before reaching the suffragette Mary Richardson as she took a blade to one of the gallery's masterpieces on the eve of the First World War.

After nine years there, Marie begins to feel the tug of restlessness. A decisive change comes in the form of a winter trip to Paris, where, with the arrival of an uninvited guest and an unexpected encounter, her carefully contained world is torn open.

Asunder is a rich, resonant novel of beguiling depths and beautiful strangeness, exploring the delicate balance between creation and destruction, control and surrender.

Excerpt

ONEThey call us guards, warders, invigilators, room keepers, gallery assistants. We are watchmen, sentinels, but we don’t polish guns, shoes or egos. We are custodians of a national treasure, a treasure beyond value stored behind eight Corinthian columns of a neoclassical façade, the dreams of the ancients stuccoed to our building. And our title should honour that. ...

Discussion Questions

1. Early in the novel Marie concedes that her position as guard is “actually suited to those afflicted by” acedia , a state of torpor in which a person no longer cares about her position or condition in the world. She claims to be free of the ailment, stating (on page 2): “ . . . I do not suffer from boredom or listlessness.” Yet we rarely see her act — at least in the beginning of the novel — and her primary interest seems to be inaction or immobility in one form or another. Do you agree with Marie that she does not suffer from acedia?2. One could say that Marie is defined by her inaction. As a museum guard, she considers intervening several times (on pages 65 and 68, for example) but stays still. She never voices her opinion of Daniel’s poetry to him, and her response to his timid advance in Paris is to remain silent. Do you see a change in this aspect of her character as the novel progresses?

3. The story of Mary Richardson’s attack on Velázquez’s Venus seems to haunt Marie nearly as much as it did her great-grandfather Ted. But she hints (on page 30) that her loyalties are divided: “I loved him just a tiny bit more for not having reached her in time.” What do you think the appeal of such an attack might be to someone who respects great works of art as much as Marie does?

4. Richardson herself claimed that her attack on the Rokeby Venus was in protest of the recent imprisonment of the prominent suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, who was, she claimed, “the most beautiful character in modern history.” Do you think the attack was purely an act of vandalism? If not, what kind of message do you think Richardson sent with her protest?

5. Marie is fascinated when she first learns about the phenomenon of craquelure (on pages 60–62), the network of cracks that develop through “release of stress ” in an old oil painting. Almost immediately after hearing the art historian describe this process, she begins to notice “small changes in mood” and finds it increasingly difficult to exert her self-control. What other examples of craquelure do you observe in Marie?

6. How does this concept of craquelure as a metaphor contrast with the violent slashes that Mary Richardson left in the Rokeby Venus? Do you see a metaphor for any part of Marie’s life in those slashes?

7. In Paris, Marie and Daniel receive an unexpected guest: Pierre, the self-medicating poet. On page 147 Marie complains: “Lying there, just lying there. And yet, from the moment he appeared to the moment he departed, Pierre exerted his influence. How could it be that someone who spent most of his time immobile could have such a strong hold on my friend?” How would you answer that question?

8. What do you think Pierre’s role is in the novel? What purpose does his appearance serve in Marie’s gradual awakening?

9. In contrast to her time with Pierre, Marie’s brief encounter with Marc Cointe — who is described both as a chatelain (the owner and controller of an estate) and as a clochard (a vagrant) — is marked by startling movements, even a chase. What do you think drives Marie to follow Cointe when he runs away from her?

10. Decay and decomposition are ever-present themes in this novel. Craquelure is a form of slow decomposition, of course, and Marie tracks the decay of moths in her miniature landscapes with avid interest. When she finally destroys the landscapes, Marie takes particular satisfaction in “the yielding of the eggshells,” which crumble away to dust. Are there other images of decay or decomposition that stand out to you? How are they significant in the novel’s development?

11. As Marie destroys the landscapes that have been her hobby and “collection” for so long, she says, “The more I thought back on the chatelain the greater my contempt for these misshapen things” (page 183). Why do you think that is?

12. How does Marie’s destruction of her landscapes compare with Mary Richardson’s attempted destruction of the Venus?

13. Why do you think Marie quits her job?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more