BKMT READING GUIDES

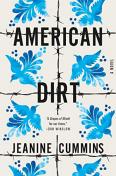

American Dirt: A Novel

by Jeanine Cummins

Hardcover : 400 pages

742 clubs reading this now

42 members have read this book

Lydia lives in Acapulco. She has a son, Luca, the love of her life, and a wonderful husband who is a journalist. And while cracks are beginning to show in ...

Introduction

Jeanine Cummins's American Dirt, the #1 New York Times bestseller and Oprah Book Club pick that has sold over three million copies

Lydia lives in Acapulco. She has a son, Luca, the love of her life, and a wonderful husband who is a journalist. And while cracks are beginning to show in Acapulco because of the cartels, Lydia’s life is, by and large, fairly comfortable. But after her husband’s tell-all profile of the newest drug lord is published, none of their lives will ever be the same.

Forced to flee, Lydia and Luca find themselves joining the countless people trying to reach the United States. Lydia soon sees that everyone is running from something. But what exactly are they running to?

Excerpt

One of the very first bullets comes in through the open window above the toilet where Luca is standing. He doesnâ??t immediately understand that itâ??s a bullet at all, and itâ??s only luck that it doesnâ??t strike him between the eyes. Luca hardly registers the mild noise it makes as it flies past and lodges into the tiled wall behind him. But the wash of bullets that follows is loud, booming, and thudding, clack-clacking with helicopter speed. There is a raft of screams, too, but that noise is shortÃ?Âlived, soon exterminated by the gunfire. Before Luca can zip his pants, lower the lid, climb up to look out, before he has time to verify the source of that terrible clamor, the bathroom door swings open and Mami is there. â??Mijo, ven,â? she says, so quietly that Luca doesnâ??t hear her. Her hands are not gentle; she propels him toward the shower. He trips on the raised tile step and falls forward onto his hands. Mami lands on top of him and his teeth pierce his lip in the tumble. He tastes blood. One dark droplet makes a tiny circle of red against the bright green shower tile. Mami shoves Luca into the corner. Thereâ??s no door on this shower, no curtain. Itâ??s only a corner of his abuelaâ??s bathroom, with a third tiled wall built to suggest a stall. This wall is around five and a half feet high and three feet longâ??just large enough, with some luck, to shield Luca and his mother from sight. Lucaâ??s back is wedged, his small shoulders touching both walls. His knees are drawn up to his chin, and Mami is clinched around him like a tortoiseâ??s shell. The door of the bathroom remains open, which worries Luca, though he canâ??t see it beyond the shield of his motherâ??s body, behind the half barricade of his abuelaâ??s shower wall. Heâ??d like to wriggle out and tip that door lightly with his finger. Heâ??d like to swing it shut. He doesnâ??t know that his mother left it open on purpose. That a closed door only invites closer scrutiny. The clatter of gunfire outside continues, joined by an odor of charÃ? coal and burning meat. Papi is grilling carne asada out there and Lucaâ??s favorite chicken drumsticks. He likes them only a tiny bit blackened, the crispy tang of the skins. His mother pulls her head up long enough to look him in the eye. She puts her hands on both sides of his face and tries to cover his ears. Outside, the gunfire slows. It ceases and then returns in short bursts, mirroring, Luca thinks, the sporadic and wild rhythm of his heart. In between the racket, Luca can still hear the radio, a womanâ??s voice announcing Ã?¡La Mejor 100.1 FM Acapulco! followed by Banda MS singing about how happy they are to be in love. Someone shoots the radio, and then thereâ??s laughter. Menâ??s voices. Two or three, Luca canâ??t tell. Hard bootsteps on Abuelaâ??s patio. â??Is he here?â? One of the voices is just outside the window. â??Here.â? â??What about the kid?â? â??Mira, thereâ??s a boy here. This him?â? Lucaâ??s cousin AdriÃ?¡n. Heâ??s wearing cleats and his HernÃ?¡ndez jersey. AdriÃ?¡n can juggle a balÃ?³n de fÃ?ºtbol on his knees fortyÃ?Âseven times without dropping it. â??I donâ??t know. Looks the right age. Take a picture.â? â??Hey, chicken!â? another voice says. â??Man, this looks good. You want some chicken?â? Lucaâ??s head is beneath his mamiâ??s chin, her body knotted tightly around him. â??Forget the chicken, pendejo. Check the house.â? Lucaâ??s mami rocks in her squatting position, pushing Luca even harder into the tiled wall. She squeezes against him, and together they hear the squeak and bang of the back door. Footsteps in the kitchen. The intermittent rattle of bullets in the house. Mami turns her head and notices, vivid against the tile floor, the lone spot of Lucaâ??s blood, illuminated by the slant of light from the window. Luca feels her breath snag in her chest. The house is quiet now. The hallway that ends at the door of this bathroom is carpeted. Mami tugs her shirtsleeve over her hand, and Luca watches in horror as she leans away from him, toward that telltale splatter of blood. She runs her sleeve over it, leaving behind only a faint smear, and then pitches back to him just as the man in the hallway uses the butt of his AKÃ?Â47 to nudge the door the rest of the way open. There must be three of them because Luca can still hear two voices in the yard. On the other side of the shower wall, the third man unzips his pants and empties his bladder into Abuelaâ??s toilet. Luca does not breathe. Mami does not breathe. Their eyes are closed, their bodies motionless, even their adrenaline is suspended within the calcified will of their stillness. The man hiccups, flushes, washes his hands. He dries them on Abuelaâ??s good yellow towel, the one she puts out only for parties. They donâ??t move after the man leaves. Even after they hear the squeak and bang, once more, of the kitchen door. They stay there, fixed in their tight knot of arms and legs and knees and chins and clenched eyelids and locked fingers, even after they hear the man join his comÃ? patriots outside, after they hear him announce that the house is clear and heâ??s going to eat some chicken now, because thereâ??s no excuse for letting good barbecue go to waste, not when there are children starving in Africa. The man is still close enough outside the window that Luca can hear the moist, rubbery smacking sounds his mouth makes with the chicken. Luca concentrates on breathing, in and out, without sound. He tells himself that this is just a bad dream, a terrible dream, but one heâ??s had many times before. He always awakens, heart pounding, and finds himself flooded with relief. It was just a dream. Because these are the modÃ? ern bogeymen of urban Mexico. Because even parents who take care not to discuss the violence in front of them, to change the radio station when thereâ??s news of another shooting, to conceal the worst of their own fears, cannot prevent their children from talking to other children. On the swings, at the fÃ?ºtbol field, in the boysâ?? bathroom at school, the gruesome stories gather and swell. These kids, rich, poor, middleÃ?Âclass, have all seen bodies in the streets. Casual murder. And they know from talking to one another that thereâ??s a hierarchy of danger, that some families are at greater risk than others. So although Luca never saw the least scrap of evidence of that risk from his parents, even though they demonstrated their courage impeccably before their son, he knewâ??he knew this day would come. But that truth does nothing to soften its arrival. Itâ??s a long, long while before Lucaâ??s mother removes the clamp of her hand from the back of his neck, before she leans back far enough for him to notice that the angle of light falling through the bathroom window has changed. Thereâ??s a blessing in the moments after terror and before confirmation. When at last he moves his body, Luca experiences a brief, lurching exhilaration at the very fact of his being alive. For a moment he enjoys the ragged passage of breath through his chest. He places his palms flat to feel the cool press of tiles beneath his skin. Mami collapses against the wall across from him and works her jaw in a way that reveals the dimple in her left cheek. Itâ??s weird to see her good church shoes in the shower. Luca touches the cut on his lip. The blood has dried there, but he scratches it with his teeth, and it opens again. He understands that, were this a dream, he would not taste blood. At length, Mami stands. â??Stay here,â? she instructs him in a whisper. â??Donâ??t move until I come back for you. Donâ??t make a sound, you understand?â? Luca lunges for her hand. â??Mami, donâ??t go.â? â??Mijo, I will be right back, okay? You stay here.â? Mami pries Lucaâ??s fingers from her hand. â??Donâ??t move,â? she says again. â??Good boy.â? Luca finds it easy to obey his motherâ??s directive, not so much because heâ??s an obedient child, but because he doesnâ??t want to see. His whole family out there, in Abuelaâ??s backyard. Today is Saturday, April 7, his cousin YÃ?©niferâ??s quinceaÃ?±era, her fifteenth birthday party. Sheâ??s wearing a long white dress. Her father and mother are there, TÃ?Âo Alex and TÃ?Âa Yemi, and YÃ?©niferâ??s younger brother, AdriÃ?¡n, who, because he already turned nine, likes to say heâ??s a year older than Luca, even though theyâ??re really only four months apart. Before Luca had to pee, he and AdriÃ?¡n had been kicking the balÃ?³n around with their other primos. The mothers had been sitting around the table at the patio, their iced palomas sweating on their napkins. The last time they were all together at Abuelaâ??s house, YÃ?©nifer had accidentally walked in on Luca in the bathroom, and Luca was so mortified that today he made Mami come with him and stand guard outside the door. Abuela didnâ??t like it; she told Mami she was coddling him, that a boy his age should be able to go to the bathroom by himself, but Luca is an only child, so he gets away with things other kids donâ??t. In any case, Luca is alone in the bathroom now, and he tries not to think it, but the thought swarms up unbidden: those irritable words Mami and Abuela exchanged were perhaps the very last ones between them, ever. Luca had approached the table wriggling, whispered into Mamiâ??s ear, and Abuela, seeing this, had shaken her head, wagged an adÃ? monishing finger at them both, passed her remarks. She had a way of smiling when she criticized. But Mami was always on Lucaâ??s side. She rolled her eyes and pushed her chair back from the table anyway, ignoring her motherâ??s disapproval. When was thatâ??ten minutes ago? Two hours? Luca feels unmoored from the boundaries of time that have always existed. Outside the window he hears Mamiâ??s tentative footsteps, the soft scuff of her shoe through the remnants of something broken. A solitary gasp, too windy to be called a sob. Then a quickening of sound as she crosses the patio with purpose, depresses the keys on her phone. When she speaks, her voice has a stretched quality that Luca has never heard before, high and tight in the back of her throat. â??Send help.â?ÂDiscussion Questions

Welcome to the Reading Group Guide for American Dirt. Please note: In order to provide reading groups with the most informed and thought-provoking questions possible, it is necessary to reveal important aspects of the plot of this novel—as well as the ending. If you have not finished reading American Dirt, you may want to wait before reviewing this guide.1. Throughout the novel, Lydia thinks back on how, when she was living a middle-class existence, she viewed migrants with pity: “All her life she’s pitied those poor people. She’s donated money. She’s wondered with the sort of detached fascination of the comfortable elite how dire the conditions of their lives must be wherever they come from, that this is the better option. That these people would leave their homes, their cultures, their families, even their languages, and venture into tremendous peril, risking their very lives, all for the chance to get to the dream of some faraway country that doesn’t even want them” (chapter 10, page 94). Do you think the author chose to make Lydia a middle-class woman as her protagonist for a reason? Do you think the reader would have had a different entry point to the novel if Lydia started out as a poor migrant? Would you have viewed Lydia differently if she had come from poor origins? How much do you identify with Lydia?

2. Sebastián persists in running his story on Javier even though he knows it will put him and his family in grave danger. Do you admire what he did? Was he a good journalist or a bad husband and father? Is it possible he was both? What would you have done if you were him?

3. Lydia looks at Luca and thinks to herself: “Migrante. She can’t make the word fit him. But that’s what they are now. This is how it happens” (chapter 10, page 94). Lydia refers to her and Luca becoming migrants as something that happened to them rather than something they did. Do you think the author intentionally made this sentence passive? Do you think language allows us to label things as “other” that is, in a way, tantamount to self-preservation? Does it allow us to compartmentalize things that are too difficult to comprehend?

4. When Lydia is at the Casa del Migrante, she learns the term cuerpomático—“human ATM machine”—and what it means. Were you surprised to learn how dangerous the passage is, and for female migrants in particular?

5. When Lydia, Luca, Soledad, and Rebeca are at the Casa del Migrante, the priest warns them to turn back: “If it’s only a better life you seek, seek it elsewhere…. This path is only for people who have no choice, no other option, only violence and misery behind you” (chapter 17, page 168). Were you surprised that he would be issuing such a dire warning when he must know how desperate they are to be there in the first place? Under what conditions might you decide to leave your homeland?

6. When they get to the US–Mexican border, Beto says, “This is the whole problem, right? Look at that American flag over there—you see it? All bright and shiny; it looks brand-new. And then look at ours. It’s all busted up and raggedy” (chapter 26, page 273). Later he says, “I mean, those estadounidenses are obsessed with their flag” (chapter 26, page 274). Do you agree with Beto? Do the flags symbolize something more than just the countries they represent?

7. The term “American” only appears once in the novel. Did you notice? Why do you think the author made this choice?

8. When Luca finally crosses over to the United States, he’s disappointed: “The road below is nothing like the roads Luca imagined he’d encounter in the USA. He thought every road here would be broad as a boulevard, paved to perfection, and lined with fluorescent shopfronts. This road is like the crappiest Mexican road he’s ever seen. Dirt, dirt, and more dirt” (chapter 31, page 329). Discuss the significance of the title, American Dirt. What do you think the author means by it?

9. “Lydia had been aware of the migrant caravans coming from Guatemala and Honduras in the way comfortable people living stable lives are peripherally aware of destitution. She heard their stories on the news radio while she cooked dinner in her kitchen. Mothers pushing strollers thousands of miles, small children walking holes into the bottoms of their pink Crocs, hundreds of families banding together for safety, gathering numbers as they walked north for weeks, hitching rides in the backs of trucks whenever they could, riding La Bestia whenever they could, sleeping in fútbol stadiums and churches, coming all that way to el norte to plead for asylum. Lydia chopped onions and cilantro in her kitchen while she listened to their histories. They fled violence and poverty, gangs more powerful than their governments. She listened to their fear and determination, how resolved they were to reach Estados Unidos or die on the road in that effort, because staying at home meant their odds of survival were even worse. On the radio, Lydia heard those walking mothers singing to their children, and she felt a pang of emotion for them. She tossed chopped vegetables into hot oil, and the pan sizzled in response. That pang Lydia felt had many parts: it was anger at the injustice, it was worry, compassion, helplessness. But in truth, it was a small feeling, and when she realized she was out of garlic, the pang was subsumed by domestic irritation. Dinner would be bland” (chapter 26, pages 276–77). Do you think the narrator intends for the reader to wholeheartedly censure Lydia in this scene? Do you think Lydia is a stand-in for the reader and that the author is sending a broader message? After reading the author’s note, do you think the author includes herself in this group?

10. “I heard if your life is in danger wherever you come from, they’re not allowed to send you back there.”

To Lydia it sounds like mythology, but she can’t help asking anyway, “You have to be Central American? To apply for asylum?”

Beto shrugs. “Why? Your life in danger?”

Lydia sighs. “Isn’t everyone’s?”

(chapter 26, page 277)

If you were writing the rules for asylum eligibility, what would they be?

11. Toward the end of the novel, Soledad “sticks her hand through the fence and wiggles her fingers on the other side. Her fingers are in el norte. She spits through the fence. Only to leave a piece of herself there on American dirt” (chapter 28, page 301). Why do you think Soledad spits over the border? Is doing so a victory for her?

12. “Luca wonders if they’re moving perpendicular to that boundary now, that place where the fence disappears and the only thing to delineate one country from the next is a line that some random guy drew on a map years and years ago” (chapter 30, page 317). In his 1971 book Theory of Justice, the philosopher John Rawls came up with what he called the “veil of ignorance.” Rawls asked readers to think about how they would design an ideal society if they knew nothing of their own sex, gender, race, nationality, individual tastes, or personal identity.

Do you think the decision-makers of the borders might’ve made a different decision if they’d donned the veil of ignorance? Do you think borders are a necessary evil or might their delineation serve a societal good? Do you think that the world would be a better place if we all brought Rawls’s thought experiment to bear in our everyday individual and collective decision-making?

13. Why do you think there are birds on the cover of the novel?

14. “But the moment of the crossing has already passed, and she didn’t even realize it had happened. She never looked back, never committed any small act of ceremony to help launch her into the new life on the other side. Nothing can be undone. Adelante” (chapter 30, page 323). Do you think Lydia is better or worse off for not having known about the moment of her boundary crossing? What importance do rituals have in marking milestones in our lives? Can the done be undone, the past rewinded?

15. Was Javier’s reaction to Marta’s death at all understandable? Humanizing? Do you believe that he didn’t want Lydia dead? Is what he did, in the name of his daughter, any less paternal than what Lydia does for Luca is maternal?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 17 of 18 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more