BKMT READING GUIDES

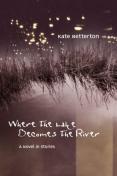

Where the Lake Becomes the River

by Kate Betterton

Hardcover : 368 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Growing up amidst Mississippi's racial tensions, Parrish McCullough is shadowed by secrets and haunted by spirits. She wrestles with “The Truth About Life After Death” after her father dies, and she sees his ghost sitting beside his casket. Parrish is a gifted artist who desperately hopes to leave small-town life for a career in art-but there's no money. She fears her mother will lapse into madness if she goes, and she keeps getting distracted by the wrong kind of man. When Civil Rights workers arrive in Mississippi, Parrish takes a chance that sends her onto the razor's edge between living and dying, learns of the soul's survival-and finds an unexpected romance. Lush, vivid and wildly entertaining, Where the Lake Becomes the River brings to life an unforgettable extended Southern family, along with its dreams, its disappointments-and, yes, even its beloved ghosts. "Homespun and profound, deadpan and poetic, hilarious and heartbreaking."(--Joseph Bathanti); "Delectable, unforgettable...a current of gorgeous prose and irresistible storytelling that will sweep you away."(--Pamela Duncan); "Great tenderness...swagger and sass." (--Virginia Holman); "Lush as a house covered in kudzu...as mysterious as creatures swimming unseen in a cool, dark, southern pond."(--Nancy Peacock)

Excerpt

Okay, relax; I've got you. Look up. That's the Big Dipper-follow Daddy's hand. See? The handle and the bowl: you've got your first constellation. Aren't the stars beautiful? Now make a wish. --Walt McCullough, backyard star seminar Mama's like a woman hosting a garden party and there's a coiled copperhead about to strike her foot through her dye-matched slipper, but she either can't see it, or she'd rather be bitten than make a scene. The snake in the grass is my sister Sally's fiancé Glenn, who's hell-bent on seducing me. “Well, honey,” Mama says, “you can't very well not go at this point, because you've already accepted.” She's talking around the pins in her mouth, and they wiggle like mouse whiskers. She's pulled me from my room where I was sorting through a blizzard of term papers, giving them a final read before burning them down at the bayou in a ceremonial farewell to life in Athena. She marched right in, ignoring my shut door and the print I'd tacked on it of Munch's “The Scream”-posted as a clear warning about my state of overwhelm. She dragged me to her sewing machine. “That was last month and this is now. I've changed my mind.” It's summer in the Mississippi Delta. We're up in her glassed-in sewing room that sails above the plum trees like a tiny barque forever tossed in a sea of leaves. The air conditioner shudders and shakes, barely keeping the heat at bay. She's sewing me a blouse I'll never wear. I'll pack it anyway, to please her, in one of the old suitcases I'm taking to college, ones she and Daddy carried around the world on his tours of duty. I've already packed his little leather notebook of quotes about the stars, although I haven't quite asked her yet if I can have it. “It's the Fourth of July, Parrish,” she says. “They're launching Glenn's raft. He and Sally will be devastated if you don't show up.” She twirls me like a cotillion deb to attack the other sleeve. Mama has strong, clever fingers, brown from gardening, that pluck down the un-sewn sleeves like a soloist playing a harp. A pinprick makes me jump. I suck a drop of blood from my wrist. “I'm not going,” I say pleasantly, stifling my irritation. I can't tell her about Glenn, because it's my job to protect her. When Daddy died she almost had a nervous breakdown, and she's always poised right on that cusp. I add Glenn's treachery to the list of things she'll never know. “The whole family will be there,” Mama says. By this she means my brothers Jesse and Griff, home for the summer but leaving, like me, in the fall, my sister Louise and her husband Ethan, and Sally, just now dating again after her husband Carl died in Vietnam. Sally's son Winston will be along, with some of his friends. Mama is certain this will be our last family picnic together, and she may be right. Griff lives in New York now, and Jesse's just quit Ole Miss, planning to leave for California's hippie scene. My father can't attend; he died of a heart attack when I was six. Mama's always ladylike in her summer dresses, unlike me in my faded cotton shirts-when my brothers are ready to toss a shirt out, is when it's soft enough for me. Today she's wearing a cherry-blossom dress as delicate as a kimono. Ordinarily she'd wear matching shell-pink pumps, but since she's not leaving the house, she's got on golden slippers that curl back at the toes like shoes a harem girl or genie would wear. Our old friend Solly Goldstein's grown rich selling these peculiar golden mules to Athena's ladies--they cost more than a brand new pair of Bass Weejuns. “Glenn's not family yet,” I say. “He's just her boyfriend.” Sally's my oldest sister, but technically she's my cousin; she was orphaned by a drunk driver when she was two, and adopted by my parents. She's breezy and confident and smart, but Mama worries about her like she frets about all of us. Sally has a nursing degree, owns her own home, and has always been highly skilled at taking care of herself--at least I thought so until she starting dating Glenn. At a recent cookout in our back yard, he followed me around until I squeezed in at the table between my brothers, who complained good-naturedly, but shifted to make room. While Sally was inside packing up some leftovers, Glenn caught me out in Mama's car playing the radio. He slipped in quick, put his big paw on my thigh and whispered, “Why don't you slip away some night and go for a moonlight cruise with me on my raft?” His molten-copper hair gleamed like a fallen angel's, and his cerulean eyes were cloudy and sly. Sally works nights at the hospital. I scrunched against the door and blurted, “Are you crazy?” I jumped out, zipped inside to my room and slammed the door. I watched through the blinds until they drove off. “If you don't come,” Mama says, “it'll spoil the holiday for everyone.” She's several inches shorter than me, so I look down at the top of her head as she circles around tugging and basting. My father was tall; our petite little Mama gave birth to giants--a peach tree spawning cedars. My brothers are over six feet, my sisters just under, and at five-seven, I'm the shortest of the batch. “Then y'all will all just have to sink without me.” “Don't say that! Don't tempt fate!” For my day at home, I've got on a pair of cut-off jeans raveled at the hems and worn almost to disreputability at the seat, topped by a faded green madras shirt whose collar is tattered to bits. Green flip-flops from the Blue Moon Sundries--a dollar ninety-nine plus tax--complete my ensemble. What did Mama do in a past lifetime to end up with a daughter like me? Yet I suspect she conceals an odd sort of pride in my refusal to conform to Deep South womanly dress codes. She stands back looking at me, studying the way the blouse hangs, but also sizing me up. I inherited her womanly curves and Daddy's slender, athletic grace, so I look pretty good in a bikini. I tan easily. I have my dad's looks, Scottish and English mixed with Cherokee-a strong nose, stubborn chin, and lips that are full and firm, and quick to laugh. I can almost hear Mama thinking, “All the right materials are there, but how can I mold her into a proper Southern lady?” The answer is, she can't. I couldn't care less about matching outfits, make-up, or feminine wiles. I must be fairly attractive, since I get a lot of male attention-often, way more than I want. But maybe from having to hold my own with brothers, I've never practiced the female art of letting boys win, or pretending they know more, for the sake of the masculine ego. My brother Griff says that by Asian astrology, I was born in the Year of the Tiger-the worst possible sign for ever getting married, since Tiger women are way too bold and independent. If I ever have a mate, he'll have to be secure enough not to be threatened by the real me--and, hopefully, to enjoy it. Mama shucks the blouse up over my head, and plops down at her ancient Singer to run a seam. “Who knows if his raft will even float?” I say. “He won it in a card game from a man in Itta Bena who built it in his carport.” “Oh, it'll float all right. Glenn says it's made of steel and good cedar. He's tested it in the lake.” “I thought you disapproved of gambling.” “I just want Sally to be happy!” “It'll sink like a stone with all souls aboard, and I'll have to write the obit. I'm on that beat--police beat, waterfront, and obits. The raft goes down, the story's mine on all three counts.” I work part-time on the Athena Times, saving money to augment my scholarship for art school. I long for the solitude of an academic life, far from anyone who thinks they know me. I pack, I plan, but the truth is, I'm scared to go and leave her here all alone-I'm the youngest and the last. She almost went crazy when Daddy died. What if she does it again without me here to watch out for her? “Stop it, Parrish,” Mama says. Her figure's gone just slightly plump. The face my father fell in love with is still lovely--fine cheekbones and a noble brow. She's dignified and poignant, like an ancient Grecian bust lost to the ocean floor. Even now, focused on a task, she has an air of being off in some distant, private landscape. I've watched her all these years, noted every detail, yet she remains a portrait that's blurred, a secret never shared. She yanks the blouse over my head and guides my arm through the sleeves, recalling dim memories of toddlerdom and being dressed. It's her day off from Customer Service at the hospital--she could just relax, but she does love to sew. “I'll write a fine obituary,” I say. Being trussed up in straight pins brings out the worst in me. Her face clouds over, but I'm relentless. “All the McCulloughs gone to a watery grave, and I'm the sole survivor. In lieu of flowers, send donations for my college fund.” She plunks down on her sewing stool and bursts into tears. I'm instantly contrite. “I'm just kidding, Mama! Don't take it to heart.” I pat her shoulder. Her crying sends tremors through her body that I feel in my palm. As my life expands, hers seems to shrink, shriveling away in the dust of my leaving. I could stay and get some job, but I can't wait to leave Athena, Mississippi behind. I long to paint, and learn new techniques, and study the masters--not just their paintings, but how they made a living doing art. “I hate to hurt Glenn's feelings,” Mama says. “He really doesn't have a family, you know.” “Ummm,” I say. I rub her shoulders. They're tense, like Atlas carrying the weight of the world. One night when Mama and my brothers were all out, Glenn knocked on our door. His smug look, like a hyena who's stalked its prey to the edge of a cliff, said he knew I was alone. “Hi, gorgeous,” he said. “My car broke down.” He grasped the small gold cross I wear, not because I have any reliable sort of faith, but because Daddy gave it to me when I was small. “Pretty,” he said, pressing his hands down. “Can I come in and use your phone?” I felt like a woman might feel when she's run out of gas late at night, and a truckload of drunken men stagger up to her car. “No, you can't!” I said, slamming the door. Then I worried maybe he really had broken down and I'd catch hell for not helping him--hospitality was a law in Mississippi, not aiding someone in need a deadly sin. But no one said anything: it was obvious he'd lied. I wanted to tell Sally, but knew from experience that he'd explain it all away. Men like him convince themselves they're doing nothing wrong--and that can make them all too believable to a woman who loves them. A police car snakes by, out beneath the plum branches, the same cops who've shadowed me for months. I call them Tweedledum and Tweedledee. They never show their faces; it's always glimpses in the mirror when I'm driving, like last night coming home from a staff party at my editor's house. Blinding lights appeared and hung in close, right on my bumper, all the way home. My heart went Whump, ka-whump! and my fingers fused to the steering wheel. I can't tell Mama, because it would worry her sick. This is the first time they've shown up in daylight. It makes me queasy. I watch, but they seem to have gone. Mama rises, stiffly. I tug off the blouse and hand it to her. I pull her into a hug, and see my face in her sewing mirror. I've been told I have the eyes of an old soul, a direct, searching gaze that makes some people nervous but sets others at ease, making perfect strangers feel they know me. I peer at my reflection. There's a wry expression on the lips, but something sad and lonely lingering in the eyes. “I'll go on the picnic with you,” I say. “You will?” Mama looks up, brushing back her hair with shaky hands. “Oh honey, you don't know what it means to me.” She's darkened and now she brightens, like wild flowers shadowed by a storm sweeping on past to become a tornado somewhere safely off in Alabama or Georgia. “No more talk about death and disasters, okay?” She gives me a valiant smile, looking bravely into my eyes. I manage not to laugh. Death has been her stock in trade since Daddy died. It's always, “Now when I die, I want you to have the la-la-la,” never thinking that going on about her death just adds to my insecurity. I love her dearly, but she drives me nuts. I'll go switch “The Scream” out for Van Gogh's “Self-Portrait” with his head bandaged after he sliced off his ear--a perfect indicator, to those with eyes to see: “I am going insane, and am possibly dangerous. Do not disturb.” “Mama,” I warn her, “Don't push it.” Too late now: we're on Glenn's raft, too far out to jump off and swim back to shore. Lake Chickasaw was a loop of the Mississippi until a deep-cut channel carried the river past, and made an island across from downtown Athena. Sand piles up along the margins of the island and out in the lake, making sand bars that come and go as the water builds and erases them. The best place for these is down close to where the lake becomes the river, just before the bluff at Warwick Point. Glenn's raft slid out from the marina like a giant swan churning up a steady wake. He steered it south, towards Warwick Point. It made the willows on McArthur Island sweep past in a slow green blur, shivering in the sunlight, and made breezes flow cool on my face. I stood at the bow, splashed by spray, drinking in the pungent aroma. Sunlit waves dazzled my eyes. The kids raced around. Louise and Ethan, an archeologist she met at his dig out at the Indian Mounds, leaned together on a bench, holding hands. Mama sat beside Sally, who was slapping sandwiches together at a table under the yellow canopy. My brothers and their dates drank beer, losing half their conversation to the motor's roar. Sally's dark-blond hair ruffled in the wind, plucking highlights from sun bouncing up off the water. Her eyes sparkled with a smile so happy it broke my heart. A motion above caught my eye: a hawk wheeling high above the Marina. I imagined how it saw the great loops of the river, the raft churning down the lake, and downtown's tree-lined avenues stretching back from the levee. The library would look like a miniature Greek temple; perched on the same corner were the Catholic Cathedral, First Baptist, and the Jewish Synagogue. Nearby was Abraham Park, a lush rose garden with a heart-shaped goldfish pond, where bands played on summer nights in a white gazebo, and Athena's children raced along the pathways and greens. The hawk sailed high over Athena's neighborhoods and cemeteries: the Old Athena Cemetery where my father's buried, the Jewish one beside it, the Chinese one down the street, the Black one out at the edge of town--and finally the oldest burial place, the Indian Mounds a few miles to the north. The Blues Highway, rippled with heat mirages, cut south through flat cotton fields; Highway 82 intersected it east to west and crossed on over the Mississippi River Bridge to Arkansas. This was some of the richest land on earth, matched only by that of the Nile valley, down in Egypt land. We passed a row of towboat companies and came to a string of private residences. The largest was the home of Willard Krups, Grand Dragon of the local KKK. I borrowed Winston's binoculars to peruse the scene. Guests arrived at the Krups' dock in rafts and fancy boats. A burly guard with a buzz-cut head and a holstered pistol checked arrivals against a list on a clipboard. People milled around at picnic tables spread with fried chicken and devilled eggs. Kids chased each other while the adults drank and laughed. It was like anyone's Fourth of July bash, except that up on the lawn was a cross wrapped in rags, which they'd torch tonight as the culmination of Krups' annual private fireworks show. It wasn't illegal for him to burn it on his property; the U.S. Constitution afforded him that right. A young woman with shoulder-length dark hair like mine arrived in a speedboat. She handed the guard a cake iced like the Confederate flag, climbed out and took it, smiling and chatting, and sauntered up the dock.Discussion Questions

1. How does her encounter with the giant snake effect Parrish? She confronts Willard Krups, but he's not likely to change. Does anyone benefit from her actions? What might the pink boat cushion symbolize?2. How do the McCulloughs and Hiroshi Takashima benefit from their friendship? Why does he give Sally objects to give Parrish when she leaves for college, with his blessing?

3. What draws Harvey to Etta Fae, and she to him? Why does Walt risk so much to protect them? What leads to Officer Crawford's attitude shift? Can we entirely free ourselves from racism, or is this an ongoing, lifelong process?

4. Parrish believes “No one ever gets away with anything-what you do to others will be done to you.” Do you agree that a “Higher Justice” will ensure that the men who were so horrifically cruel to Parrish's cat and Harvey's dog will eventually get their just rewards?

5. After Walt dies, Grace appears to be going mad. Is she? How does grief manifest in the children? What role does art play in Parrish's life? What do Louise and Grace gain from their nightly “checking” ritual? What frees Parrish from the need to keep “checking?”

6. Many extraordinary events occur in this book, especially centering around Parrish. Have you experienced any “paranormal” events? Why does our culture deny such metaphysical aspects of reality?

7. Parrish fights a valiant battle, over a number of years, against her stepfather's abuse, and triumphs in the end. --Or does she? She blames herself for Lucien's death. Is her guilt justified? What does Parrish learn from Zanda's struggle to free herself from her own father's control? Did Zanda pull McBride off-balance? If so, was she wrong to do this?

8. What makes Robbie vulnerable to the “Lost Boy's ghost?” What does Parrish mean by, “Maybe we were playing 'Get the Guest' with Robbie after all, and just didn't realize it?”

9. Why does Parrish find Cam very familiar--more than a new friendship would seem to warrant? Why does Cam betray Parrish in New Orleans? She forgives him. Would you?

10. Why do you think Jake Harper holds back with Parrish, although it's clear there's something he wants to tell her? Why does Parrish fail to see Jake for who he really is?

11. What questions posed earlier in the book are answered in the final chapter? Why won't Grace discuss with Walt what happened to Birdie? Grace keeps Walt's family's unusual legacy a secret for many years. Should she have told her children about it earlier?

12. Parrish explores many religions and philosophies, trying to understand death, regain her lost spirituality, and redefine her beliefs. After her hospital experience, what does she believe is “the truth about life after death?” What do you believe happens when we die?

Notes From the Author to the Bookclub

Years ago, I was in a terrible car wreck that brought me right to the edge between living and dying. Recovering, I thought, “Someday I’ll write about this wreck.” Much later, I wrote a piece about someone who “wakes back up” after dying and going to Heaven. This story, with its barely-mentioned “car wreck,” became the final chapter of WHERE THE LAKE BECOMES THE RIVER, and gave the novel its underlying theme: the thin line between this world and the next. It seems that we can sometimes cross over that line and return, through unusual experiences, and in our dreams. My heroine, Parrish McCullough, grows up in a household stuffed with secrets. She’s haunted by her father’s spirit--and other, more ominous ghosts. The book involves her family, loves, and challenges, but at its core is Parrish’s struggle to understand “The Truth About Life After Death.” This enigma has haunted her since childhood, when her father died but seemed to remain nearby, intent on delivering a crucial message from beyond the grave--just the beginning of a series of extraordinary paranormal events. At some point, for most of us, someone we love will step through the doorway we call “death." I hope readers will find Parrish’s adventures wildly entertaining, but also gain, perhaps, an expanded context for what that passage may mean--and a measure of comfort from sharing Parrish’s glimpses of immortality.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 1 of 1 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more