BKMT READING GUIDES

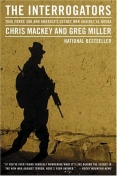

The Interrogators : Task Force 500 and America's Secret War Against Al Qaeda

by Greg Miller, Chris Mackey

Paperback : 528 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

In a narrative that reads like a spy thriller, Chris Mackey takes us inside a small team of American military interrogators confronting an enemy unlike any other they had ever seen--in a war not of missiles and tanks, but of sleeper cells and suicide bombers. Mackey reveals how his team managed to crack some of the hardest cases they encountered, creating highly sophisticated ruses and elaborate trickery to bluff, worry, and confuse their opponents into yielding up precious information. He tells as well of mistakes made: blown interrogations, abuses against prisoners, and failures of American intelligence. THE INTERROGATORS is a riveting memoir that lifts the curtain for the first time on the hidden backstage of America’s war against terrorism.

Excerpt

TRAINING Most students slipped quite naturally out of their school uniforms at Immaculate High School in Danbury, Connecticut, and into the country’s better universities. I slipped out of my uniform and into army fatigues. I was seventeen when I enlisted in 1989, and it came as a surprise to all of my friends but one, Sean McGinty, who enlisted with me. We suffered from a debilitating condition: too many siblings. Our working-class parents—my father was a telephone line repairman, McGinty’s an accountant—had made it clear some time earlier that we were going to have to pay our own way through college. And so we decided to enlist together, jokingly trying to be the first to complete the army oath so as to be “senior” to the other in our new military lives. McGinty skipped a phrase or two, arriving at the “so help me God” line first. I would argue for years that he had invalidated his oath by jumping ahead, but that was a debate I would never win. Originally we thought the infantry would be good. The army brochures made it all look fairly glamorous, with lots of pictures of armored personnel carriers rolling through German landscapes and Teutonic villagers smiling at passing Americans. But my father had been an artilleryman who was called up from the Connecticut National Guard during Korea, and he wanted me to pursue a military field far away from cannons and endless gunnery drills. The Saturday morning after McGinty and I signed up, I found myself waiting in a parking lot with my father, while a parade of distinctly unmilitary people walked into a vaguely industrial-looking building surrounded by a chain-link fence. A yellow fifties hot rod pulled into the lot and a tall man stepped out and stooped to pick up a knapsack from the rumble seat. My father, taller still, stretched out his big hand and the two men smiled at each other and exchanged greetings. “So this is your boy,” the man said, pausing to conduct a quick inspection. I was inspecting him, too. He sported an outrageous pompadour haircut that looked about as military as a ponytail. His wrinkled battle dress uniform was practically white with wear. An absurd unit patch on his shoulder depicted a pilgrim with a blunderbuss. The first few minutes reinforced every stereotype about the reserves and national guard. The man, First Sergeant Staib, excused himself to tend to the business of his office, which appeared to consist of drinking Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and kidding around with his colleagues. My father and I stood in the vestibule looking at plaques honoring Soldier of the Year for 1975 and the winning platoon in the 1969 handball competition. Only the posters exhorting soldiers to “protect classified documents” and “Beware the Bear” indicated there might be something here of interest. All the while, overweight soldiers with gray hair and outdated uniforms pushed by to join a gaggle in the center of a gymlike open area. After his doughnut, Staib came out of the adjoining office, stood at the top of the open area, and bellowed, “Fall in!” His Hollywood-quality command voice startled me. The resulting movement wasn’t exactly a scramble, more of a high-speed shuffling, but the suddenness of the soldiers’ motion, and their final arrangement in neat little squares of troops, was more than a little impressive. Suddenly Staib’s uniform didn’t look so wrinkled after all. After the formation, Staib brought my father and me into an office. The unit’s commander was there, a Major Gregoire, and a very old female officer who looked so much like a nun I nearly called her “sister.” They asked me if I knew what the unit did, and I said something like “only that you are linguists.” They smiled and said that was more or less correct, but that there was more to the story. In fact, they were an interrogation unit, responsible for questioning prisoners of war, refugees, border crossers, and other sources of intelligence information. Interrogators, I thought. After a chat with Staib, the commander, and the nun, I was taken around the dirty facility and introduced to the various groups. Sizing them up, I was a little concerned that they were the grown-up versions of the nerds and dweebs I had tried so hard to steer clear of in school—maybe a little conscious that I was too close to them on the social ladder for comfort. The last thing we did was sit in on a practice interrogation. A large group of reservists stood or sat around a little wooden table. A man about thirty with a very big nose and mustache sat in one chair, while a slightly older, balding man sat opposite. Sitting behind the big-nosed man was a particularly old fellow with white hair, glasses, and a crooked front tooth. If there had been a few banjos, it might have been a scene from a Louisiana bayou. The balding man was the interrogator. He posed questions to the big-nosed fellow in English. The crooked-toothed guy translated the English into German, whereupon Big Nose answered in German. The German was translated back into English, and the balding interrogator scribbled in his notebook. After the first few questions passed through this circuit, there developed a kind of disjointed conversation. “How did you come to be captured, Mah-yohr Schmidt?” Big Nose said something about conducting reconnaissance on the river Elbe for his unit. The balding guy asked questions about the prisoner’s men: why hadn’t they helped him avoid capture as they had done? He began to suggest that Schmidt was a coward. Soon the balding man was screaming at Schmidt, who in response began to look more and more dejected. This went on for some time. The script was well written. The prisoner was overcome by his ordeal. The violence of his capture had affected him deeply, and he was unprepared for the flurry of insults and baiting his interrogator offered. He was reduced nearly to tears by the grilling. Then the tenor of their conversation changed. The bald interrogator produced a cigarette. The prisoner declined, too distressed to accept. But he began to talk, yielding information about his unit as if he were unburdening himself of personal secrets he no longer wished to keep. When the show was over, I found my father in the motor pool speaking with Staib. We parted company with our uniformed hosts, making promises of speaking again soon and various nonbinding expressions of interest. My father asked for my impressions on the way home, and I told him I thought it was interesting but not exactly very military. Not being “military” was the point, my father said. “It’s the intelligence corps, after all.” That comment began to sink in. I started to realize there might be advantages to the new route, not least of which was the opportunity to study a foreign language as part of the initial training. I spoke with McGinty about all this. We debated the merits of the infantry and the intelligence corps in the bleachers of the school gym. McGinty visited the reserve unit a few weeks later and was impressed enough to at least consider a change. With some reluctance (and lots of lobbying by parents who thought the intelligence corps sounded significantly less dangerous than being an infantry grunt), we revisited our recruiter. The big sergeant seemed to accept our change of heart pretty well—almost as if he’d expected it, really. Although he tried to get us to join the intelligence corps as active-duty troops, the six-year commitment was a little too much. The training even for the reserves was long and would give us a good flavor of life in the army. If we liked it we could always switch to active duty, but going the other way—from active duty to the reserves—wasn’t possible. Sean and I signed our contracts alongside the signatures of our parents, a requirement for enlisting under the age of eighteen. We were in the army now, and achieved some minor celebrity at school because of it. We spent the rest of our senior year going to the reserve center once a month for training. We were paid, given uniforms, and because of our high school Spanish, were attached to the unit’s Latin America section. We sat spellbound weekend after weekend as Chief Warrant Officer Edward Archer, an Argentinian with a voice reminiscent of Ricardo Montalban’s, described the various techniques and methods for persuading enemy prisoners to talk. He stressed the importance of basic skills, of leveraging one’s own personality strengths, and of having a broad knowledge of military structure, tactics, and equipment. When summer arrived and high school graduation came, the other members of the reserve unit gave McGinty and me a farewell party as we prepared to depart for boot camp. The unit even gave us going-away presents: army ID cards showing our ages to be twenty-one rather than seventeen. Copyright © 2004 by Chris Mackey and Greg MillerDiscussion Questions

No discussion questions at this time.Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 1 of 1 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more