BKMT READING GUIDES

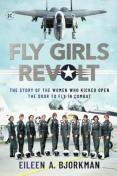

The Fly Girls Revolt: The Story of the Women Who Kicked Open the Door to Fly in Combat

by Eileen A. Bjorkman

Paperback : 288 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

In 1993, U.S. women earned the right to fly in combat, but the full story of how it ...

Introduction

This is the untold story of the women military aviators of the 1970s and 1980s who kicked open the door to fly in combat in 1993—along with the story of the women who paved the way before them.

In 1993, U.S. women earned the right to fly in combat, but the full story of how it happened is largely unknown. From the first women in the military in World War II to the final push in the 1990s, The Fly Girls Revolt chronicles the actions of a band of women who overcame decades of discrimination and prevailed against bureaucrats, chauvinists, anti-feminists, and even other military women.

Drawing on extensive research, interviews with women who served in the 1970s and 1980s, and her personal experiences in the Air Force, Eileen Bjorkman weaves together a riveting tale of the women who fought for the right to enter combat and be treated as equal partners in the U.S. military.

Although the military had begun training women as aviators in 1973, by a law of Congress they could not fly in harm’s way. Time and again when a woman graduated at the top of her pilot training class, a less-qualified male pilot was sent to fly a combat aircraft in her place.

Most of the women who fought for change between World War II and today would never fly in combat themselves, but they earned their places in history by strengthening the U.S. military and ensuring future women would not be denied opportunities solely because of their sex. The Fly Girls Revolt is their story.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

Chapter 1 We Need Women; We Don’t Need Women (1940s) Jacqueline Cochran waited impatiently in her New York City apartment while a group of men in Canada debated her fate. It was June 1941, and she hoped to ferry an American bomber aircraft across the Atlantic and deliver it to the Royal Air Force. The blonde aviatrix, considered the queen of aviation in the United States, was renowned for daredevil record-breaking flights and her cosmetics business, activities that might seem incompatible. But Cochran, who believed that women were just as good at flying airplanes as men, also believed it was “a woman’s duty to be as presentable as her circumstances of time and purse permit.” Her own time available might only be a few minutes to comb her hair and daub on fresh lipstick at the end of an eleven-hour flight, but Cochran always appeared before the cameras looking as if she had just stepped out of a beauty salon. Except for her fingernails. She never wore polish to avoid attracting attention to her masculine-appearing hands. Cochran had done everything possible to prepare for the transatlantic flight. She had no experience flying heavy, multi-engine aircraft like the bomber—she had accomplished her aviation feats over the past decade in small, nimble racers—so she’d headed to Floyd Bennett Field on Long Island for several hours of instruction in a Lockheed Lodestar. She then flew to Saint-Hubert Airport, about forty-five minutes from Montreal, home to the Atlantic Ferry Organization, or Atfero. There, she trained on the bomber she planned to ferry, a Lockheed Hudson. She passed all her check rides, or practical tests, although she had some trouble grasping a hand brake used on the ground. Given her difficulty with the brake, Atfero officials decided she would fly the bomber as a first officer; she could take the controls once airborne, but the other (male) pilot would take off and land. Cochran wasn’t happy, but there was nothing she could do. Many Atfero pilots opposed the flight. About fifty of them formed a band of objectors and called a meeting to discuss the “problem.” Cochran’s husband, Floyd Odlum, attended to plead her case while she returned to New York. “She’s on a publicity stunt,” said one pilot. It was true that Cochran had leaped at the chance to be the first woman to fly a bomber across the Atlantic, but it wasn’t her idea. She had been at a luncheon with Clayton Knight, a World War I aviator who dabbled in all sorts of aviation-related activities, such as illustrating the Ace Drummond comic strip written by World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker. Knight was recruiting U.S. pilots for Atfero; during the luncheon, he asked Cochran, “Why don’t you do some of this flying to England yourself to help dramatize the need? The publicity might help.” As Odlum dismissed the publicity concerns, another pilot said, “She’ll belittle the rest of us who have been involved in this dangerous work. This isn’t women’s work. It’s for men.” This opinion was really a fear that if a woman could do the job, it wasn’t all that dangerous. There was a small possibility the Germans might try to shoot down Cochran, but that was a risk she was willing to take. Yet another pilot hit the bottom line: “Putting a woman into the cockpit of a bomber for ferrying purposes is taking bread out of our own mouths.” But Cochran was flying one flight, not storming Atfero with a phalanx of women pilots. The last pilot to speak told Floyd, “Taking a woman into our organization will be disruptive. We’ve disapproved of your wife being here from the very moment the question was raised. We’ve simply been overruled by higher-ups.” But he conceded, “We’re not running this organization and we’ve no right to issue an ultimatum to anyone, not even Miss Cochran.” The last pilot was right. The “higher-ups” had spoken, and it was time to follow orders. Captain Grafton Carlisle was assigned to fly with Cochran. He was mad, not at Cochran but at the other men, some of whom threatened to blackball him from flying jobs for taking the assignment. Cochran arrived back in Canada on June 16, 1941. Carlisle was eager to get going. The next morning, as the two pilots and a radio officer made their final preparations, the wives of the two men arrived, ostensibly to bring sandwiches. But the women weren’t worried about their husbands’ stomachs; they were concerned about the threats made against them. The wives waited in their cars until the bomber took off. The first leg of the trip to Gander, Newfoundland, was uneventful. But the next morning, the ground roll during the takeoff run was so bumpy it felt like rolling over logs on the runway. Carlisle aborted the takeoff. Suspecting that cold had affected the oleo struts that acted as shock absorbers, he taxied back to the ramp. The crew serviced the struts and off-loaded about six hundred pounds of fuel for good measure. The takeoff was rough, but Carlisle managed to stagger into the air. With the aircraft safely airborne, Carlisle climbed out of the pilot’s seat and Cochran slid in to take the controls. Carlisle headed to the back of the airplane to pass time until a few minutes before landing, when he and Cochran would again perform the change-of-control dance. Everyone settled in for the eleven-hour flight, mostly above and in the clouds. Cochran saw the aurora borealis for the first time; she found it “weird but entrancing.” Just before daybreak, tracer bullets streaked toward them, breaking the monotony. Carlisle and the radio operator dashed into the cockpit. The crew didn’t know if the bullets were British or German, but there was a way to find out. Carlisle grabbed a signal pistol and ran to the back of the aircraft. He popped open a hatch and fired a signal bullet of a color that indicated they were a friendly aircraft. The bullets from the ground continued, and Cochran worried that maybe the Germans were trying to kill her. But perhaps the cloud cover prevented anyone below from seeing the signal from the Hudson. The bullets suddenly stopped. When they landed, they found no damage to the bomber. Cochran never learned who fired at them. For another half-century, women aviators would hear the same arguments the male pilots made in their battle to keep Cochran out of the bomber: they were just in it for glamor, combat flying was too dangerous, and they took jobs from men. Most of all, women were disruptive. *** Four decades after her death, Jacqueline Cochran remains an enigma. One of her biographers, Maryann Bucknum Brinley, summed her up as “an explosive study in contradictions,” simultaneously “generous, egotistical, penny-pinching, compassionate, sensitive [and] aggressive.” Cochran’s two autobiographies contain so much demonstrably false material that it’s difficult to know when she was telling the truth. Cochran claimed to not know when she was born or who her parents were, but she was born in 1906 in Florida’s panhandle. Her birth name was Bessie Lee Pittman; she was the youngest of five children in a working-class family. As an adult, she told people she was adopted and wove vivid stories of a childhood filled with gut-wrenching poverty. Another oft-repeated story had her picking the name “Cochran” out of a telephone book in Pensacola. But none of it was true. The truth was that around 1920, Bessie Pittman married Robert Cochran. They had a son, also Robert, who died in 1925 after setting himself on fire while playing with matches. The Cochrans divorced soon afterwards. Bessie moved to Montgomery, Alabama, to work as a hairdresser and began using the name Jacqueline. As she moved further north, she buried her past along with her son. She never mentioned her first marriage or dead son again, at least in public. And she never had another child. Cochran arrived in New York City in 1929 and landed a position at a salon in Saks Fifth Avenue. She met Floyd Odlum in 1932, and the two began dating, even though he was still married and had two sons. Odlum was one of the world’s most wealthy men. He had founded his own company in the 1920s and thrived during the Depression by snapping up depressed companies and then selling them quickly at a profit, usually 40 or 50 percent. The two made for an odd couple: Odlum, far from a looker with his horn-rimmed glasses, next to the glamorous Cochran. She claimed she loved him for his mind, and she justified their dating by saying the marriage was over, the divorce just hadn’t happened yet. Odlum sparked Cochran’s interest in aviation. She wanted to sell cosmetics on the road; to cover enough territory to make money, he suggested she should fly. Why not get a pilot’s license and fly herself? Cochran liked the idea. The Roosevelt Aviation School on Long Island advertised twenty hours of flight training for $495. Cochran was in a hurry, and Odlum bet her the $495 that she couldn’t get her license in six weeks. It was just the sort of challenge she needed. Cochran started her training on a Saturday and claimed she soloed in a little airplane called a Fleet two days later. During her first solo flight, which involved taking off and landing a few times, the engine quit. Some students would have panicked, but Cochran handled the emergency with aplomb. She glided back to the runway and touched down as if nothing had gone wrong. Three weeks later she had her license, and Odlum paid up. By 1934, Cochran had earned her commercial pilot’s license, meaning she could be paid for her flying. She was also learning how to fly just by looking at instruments inside the cockpit so she could fly in poor weather. By then, she wanted to do more than sell cosmetics: she wanted to enter airplane races. The races, common in the 1930s, garnered front-page coverage in newspapers, and winners often became famous. Cochran’s first race attempt—an international route from England to Australia—ended in Bucharest, Romania, after she realized her aircraft, a Gee Bee, wasn’t suited to such a long distance. In 1935, she founded Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics. Her signature product was Flowing Velvet, a moisturizer she developed to cure her skin problems created by flying, especially at high altitudes. That year, Cochran also set a new target for her racing ambitions: the most prestigious aviation event in the U.S., the Bendix Trophy Race, a transcontinental race founded in 1931 that took place each Labor Day weekend. The National Air Race Committee and Vincent Bendix, who manufactured innovative aircraft parts, each provided half of a $15,000 purse. Cliff Henderson, founder of the National Air Races, hoped the cash prizes would entice entrants to push the technology bounds of navigation, weather, efficiency, endurance, and speed. In 1934, Henderson had barred women from the race, saying, “Women have no more place in the National Air Races than on the automobile racetrack at Indianapolis.” He didn’t have anything against women aviators, of course, but a year earlier twenty-three-year-old Florence Klingensmith had died when a wing fell off her aircraft during a tight pylon turn at a race in Chicago. Male pilots died just about every year during the races, but Henderson apparently couldn’t stomach the thought of a woman’s death. After Frances Harrell Marsalis died in a crash at the first Women’s National Air Meet in August 1934, a writer lamented in Popular Aviation magazine, “Just one more victim of the race mania and a desire to feed death-defying thrills to a hungry public.” Without any discussion on why he considered a female pilot’s death more tragic than a man’s, he asked, “Is it worth the price?” Women pilots thought it was. They railed against Henderson’s injunction. Amelia Earhart, the most famous of them all, refused to fly actress Mary Pickford from Los Angeles to Cleveland, where Pickford was scheduled to open the races. Famed aviator Jimmy Doolittle flew Pickford instead. Henderson relented the next year, and both Earhart and Cochran started the race in Burbank. On August 31, 1935, Amelia Earhart roared down the runway at 12:34 a.m. with two male pilots playing cards in the back of her Lockheed Vega. The trio wasn’t interested in winning; they just hoped to come in fifth place to earn $500 to cover their trip expenses. They got their wish. Fog rolled in after Earhart’s takeoff, so Cochran bided time, finally lifting off at 4:22 a.m. A fence at the end of the runway snagged an antenna, leaving her with no radio. After circling her fuel-laden aircraft to gain altitude, she crossed the San Bernardino Mountains. She was in the race. But the climb had strained her engine, and an ominous vibration rattled her aircraft’s tail. As Cochran approached the Grand Canyon at daylight, she knew there were no more airports for hundreds of miles to land in an emergency. Worse, thunderstorms lay ahead. Cochran was bold, but she knew her limits. The race was over for her. She turned around and landed at a nearby airport. The next year, 1936, the women shone. Louise Thaden became the first woman to win the Bendix race, and women took three of the five prizes. Cochran didn’t race, but that year she and Floyd Odlum married. The 1937 race was a sad time. Earhart had vanished two months earlier during her round-the-globe flight, leaving a giant void in women’s aviation. Despite her heavy heart, Cochran placed third. By then, she had honed her long-distance flying skills. To keep her mouth moist, she sipped on a small bottle half-filled with cola—a full bottle fizzed and spilled at high altitudes. Except for a handful of suckers, she didn’t eat during a flight and could lose as much as six pounds. After a race, she smiled in front of microphones, grateful that reporters stood too far away to detect the deep lines of fatigue in her face. In 1938, flying a modified Seversky pursuit aircraft designed for the military, Cochran departed Burbank about two in the morning for her third attempt at the Bendix Trophy. For this race, the pilots pushed higher into the atmosphere, above twenty thousand feet. The high altitude forced them to use oxygen masks. Cochran flew through the night to the Seversky engine’s steady purr. As she crossed the Continental Divide, the engine sputtered and quit. Thinking she had run a fuel tank dry, she switched to another tank. That didn’t help. She had plenty of fuel, but it wasn’t getting to the engine. Cochran kicked the rudder pedals back and forth, and the engine started again; the abrupt motion had unseated a blockage. After rocking the wings several times, she found that if she kept the left wing down, the engine kept running. It was a bit awkward, but it worked. She zipped across the country in just eight hours and ten minutes without stopping for fuel, besting nine men for the win. After landing in Cleveland, she refueled, chatted with reporters for a few minutes, and greeted Odlum with “I need some cigarettes! I’ve been smoking a pipe all the way from Burbank—an oxygen pipe!” Newspapers, including the New York Times, splashed Cochran’s win across their front pages, coronating her as queen of U.S. aviation. Even then, some speculated that Cochran hadn’t flown the race, that it must have been a male pilot. *** In 1939, Cochran outlined a plan to Eleanor Roosevelt to get U.S. women into the cockpits of military aircraft. If the U.S. joined the war raging in Europe, women pilots could free up men for combat tasks. The plan hadn’t gone anywhere, but after ferrying the bomber in 1941, Cochran observed women pilots ferrying aircraft around England. Maybe it was time to revive her idea. Arriving back in New York from her bomber flight, Cochran planned to sleep until noon. But a call from President Franklin D. Roosevelt woke her at 9:00 a.m. Could she come to Hyde Park at noon? Over lunch, Cochran regaled Roosevelt with tales about the women ferry pilots in England; she hoped American women could do the same thing. The lunch opened doors for meetings with high-ranking War Department officials, including Brigadier General Robert Olds, who was forming a unit to ferry aircraft. He was interested but wanted to hire women on an individual basis, as civil servants or contractors; he would plug them in wherever needed. Cochran had a much bigger vision: an organization just for women pilots, an organization she would run. She feared a handful of women scattered about the country among tens of thousands of men would “simply go down as a flash in the historical pan.” Cochran’s vision languished amid Army bureaucracy for two months. In mid-September, General H. H. “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces, sent her a letter saying, “Not yet.” He had a dozen excuses: there weren’t enough qualified women pilots, there would be housing and training problems. Cochran was ready with answers. Just as in England, the women could be in an auxiliary corps with military status, separate from the men. Arnold wouldn’t budge, but he encouraged Cochran to take some women to England to fly as contractors with the British Air Transport Auxiliary. The “experiment” would prove that such an organization could work in the U.S. To reassure Cochran that Brigadier General Olds would not hire women to ferry aircraft on his own terms while she was gone, Arnold said, “I’ll keep Olds away from the women pilots.” Cochran had previously combed through Civil Aviation Authority files to come up with a list of potential women pilots for her planned organization. She sent telegrams to a few dozen, inviting them to an interview at her New York apartment. Cochran offered to pay all expenses for the trip. Ann Wood jumped at the offer. When she arrived for her interview, one of the first things she noticed was a glass case crammed full of Cochran’s racing memorabilia. She never forgot Cochran’s cigarette case, a gift from Floyd Odlum: a gold box encrusted with rubies, emeralds, and diamonds depicting the route of one of her Bendix races. In October, with Pearl Harbor still more than a month away, Wood went to England. Cochran’s women, who eventually totaled twenty-five, had eighteen-month contracts. After initial training, they ferried British aircraft around the country—Hurricanes, Spitfires, trainers, and bombers. Mary Nicholson, the first woman in North Carolina to receive a pilot’s license and also Cochran’s personal secretary, was the only fatality. She was killed on May 22, 1943, when the propeller flew off the airplane she was flying and she crashed. Even after Cochran’s pilots proved their competence, those in power weren’t ready for women pilots in the U.S. It was starting to look like the women would have to find another way into the war. *** Women pilots weren’t the only ones who wanted to support the war. Others clamored to help; many women joined civilian volunteer organizations to train as ambulance drivers or to help defend the East Coast from air attacks. Representative Edith Nourse Rogers, a Republican from Massachusetts, thought the timing was perfect to create a women’s Army auxiliary. During World War I, Rogers had served as a volunteer nurse overseas and with the American Red Cross in the U.S. From those experiences, she developed a lifelong passion for veterans’ issues. She was also sympathetic to the plight of women volunteers. Men in the armed forces were taken care of if they were injured or became ill overseas, but an injured or ill woman volunteer had to find medical care or a return trip to the U.S. on her own. Rogers wanted to fix that. In early 1941, Rogers authored a bill to establish the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). The women would work in “air raid warning service, in domestic work for the Army, and as chauffeurs and mechanics.” Rogers wanted women to be full members of the Army, and George C. Marshall, the chief of staff of the Army, agreed. But Marshall was no feminist; his interest was pragmatic. With the war looming, he was concerned about manpower shortages. He also didn’t want to waste time training men for things he considered “women’s work.” But members of his staff, along with many in Congress, pushed back on full military status for women. Rogers instead wrote a compromise bill. The women would have military ranks and benefits similar to men but would not have full overseas protections. The WAAC bill went nowhere until the attack on Pearl Harbor. With the support of Henry Stimson, the secretary of war, Rogers tweaked her original proposal and resubmitted it. The bill received a warm reception in the House. On January 21, 1942, Frances Bolton, a Republican representative from Ohio, testified at a House Military Affairs Committee that participation in “the organization fighting for freedom” would be a morale booster for women. She scoffed at the notion that women would find the work too arduous. Women did not expect the Army to be a glamorous job. Bolton said, “There is nothing the women of the country will welcome more than to have taken away that word ‘glamour.’” An Army brigadier general also testified in favor of the women’s corps, and Edgar G. Brown, the director of the National Negro Council, urged committee members to include women of all races. The bill moved to a House vote on March 17. But first, there was four hours of debate, mostly about whether women would be subject to military discipline, including court-martial (they would). Several representatives also lodged their opposition. Clare Eugene Hoffman, a Republican from Michigan, claimed that women didn’t really want to join the military; he said they wanted to stay home to sew, cook, and do other domestic chores. Andrew Somers, a Democrat from New York, was blunter, calling the bill “the silliest piece of legislation I have ever seen come into this House.” Democrat Butler Black Hare, from South Carolina, found the idea of women soldiers mortifying. He raged, “I think it is a reflection upon the courageous manhood of the country to pass a law inviting women to join the armed forces in order to win a battle… Think of the humiliation! What has become of the manhood of America?” The bill passed, 249–86. Then it was on to the Senate, where Democratic leaders predicted smooth sailing. But the bill first had to go through the Senate Military Affairs Committee, then be brought to a vote and debated. Even with minimal opposition, it took nearly two more months before the legislation passed on May 12. *** One controversy remained, not with the WAAC bill itself, but with the woman the War Department planned to install as the director: Oveta Culp Hobby, who did publicity for the Army and was the wife of former Texas governor William P. Hobby. Edgar G. Brown wrote President Roosevelt, asking him to veto the bill; Brown feared Hobby’s Southern background would hurt non-white women who wanted to serve. His fears were well founded: some women’s volunteer organizations supporting the war effort had declined to accept Black women. Brown also asked Secretary of War Stimson to avoid selecting a director from the South; he believed such a woman would not inspire confidence that “justice would be meted out to colored women.” However, Eleanor Roosevelt expressed confidence that Executive Order 8802, signed by her husband a year earlier, would ensure Black women got a fair shake. The Executive Order stated, “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” Roosevelt signed the WAAC bill on May 15; Secretary Stimson swore Hobby in as director the next morning. After the ceremony, Hobby announced that the first four hundred recruits would be sent to officer training, that forty of those would be Black, and that at least two of the first companies of women would be Black units. That afternoon, Edgar G. Brown said that, with Hobby’s announcement, he was satisfied Black women would be treated fairly. Hobby said recruiting would begin in a few weeks, but women didn’t want to wait. They swarmed or called into recruiting centers asking how to apply. So many women called local newspapers for more information that larger papers had to hire extra telephone operators. The outpouring of support for the WAAC nudged the other services into using their own “womanpower.” By the end of 1942, the Navy had WAVES, which stood for “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service,” although some claimed it meant “Women Are Very Essential Sometimes.” The Coast Guard had SPARs, which stood for “Semper Paratus—Always Ready.” The Marines also had a women’s reserve, but a Marine is a Marine. They refused to come up with a cute acronym. *** Official WAAC recruiting started with a bang. On May 27, ten thousand women poured into recruiting centers across the country. More than one thousand women barged into a center in New York City alone. Some women had been waiting since 5:00 a.m. By 8:30, 250 of them had made it inside. A guard stretched his arms across the entrance to keep more from entering. On the second day, to keep up with the seemingly endless stream of applicants, the Army decided to keep the recruiting center open that Saturday, May 30. The recruiters had Sunday, Memorial Day, off before heading back into the deluge. Finally, on Thursday, the window for initial applicants closed. One bedraggled recruiter said, “If I never see another woman again it will be too soon.” Potential recruits cut across race and class lines. Women sporting fur coats mingled with those wearing inexpensive cotton dresses. A full-blooded Creek Indian woman arrived in traditional Native American dress. She asked reporters, “Don’t you think I have more right to join than some of the other women?” Many women had jobs, and pay phones were kept busy as women called their bosses to let them know they were running late. Some lied, with one admitting she had called in sick for a nonexistent toothache. As part of their application, women stated in one hundred words or less why they wanted to join the Army. One sounded a lot like many men: “Military life has always fascinated me because of the excitement and adventure it has to offer.” Another woman, a naturalized citizen, was more heartfelt: “With my education and previous war experience, I feel partially able to pay for what I have received in this country.” Recruits could be single or married, have a high school diploma, and be aged twenty-one to forty-five years. Women also had to be of excellent character, in good physical condition, between five-feet and six-feet tall, and weigh at least 105 pounds. A woman was also expected to be “intelligent enough to understand and execute orders and protect herself.” And she had to be capable of “transport[ing] herself by marching.” On July 20, 1942, the first 440 women officer candidates reported to Fort Des Moines to begin training. After a whirlwind of paperwork, uniform issue, and indoctrination, the women assembled in the post’s theater on July 23. Oveta Culp Hobby, now referred to as Major Hobby, told them, “This is your date with destiny, and a free future will credit your contribution.… You have taken off silk and put on khaki. And all for essentially the same reason—you have a debt and a date. A debt to democracy, a date with destiny. You may be called upon to give your lives.” The women’s training was similar to the men’s: how to march, how to wear uniforms, and how to live together as a large group. The women “officers” were not commissioned officers, but the enlisted women were expected to salute the officers and address them as “Ma’am.” For all practical purposes, the women were in the Army. The first women graduated on August 29. Only eight had dropped out, three for failing to meet academic standards, one for a physical disability, and the others for administrative reasons. During the graduation ceremony, the women marched with “backs straight and khaki skirts swinging.” The two-star general presiding over the ceremony remarked, “Many of our soldiers would do well to emulate them. I am very proud to be a part of this.” Hobby attended the ceremony, along with Representative Rogers, there to see the first products of her bill. During Rogers’s commencement speech, she told the women, “You represent a dream which I conceived during the first World War.” After the speech, a captain called out, “Mary Bell Armstrong.” Armstrong strode to the front of the bandstand, saluted the general, and shook hands with him. She was now a “third officer.” The women were on their way. *** Emma Riley was among the first to apply for a commission that summer. Despite her master’s degree, the WAAC rejected her for officer training, so she enlisted. The Army sent her a notice to take a train the last Sunday of August 1942 from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Des Moines. But when she arrived at the train station with her parents, they discovered that the train didn’t operate on Sundays. Her parents drove her sixty miles to Kansas City. Her father, already upset she had enlisted in the Army instead of being an officer, was further irritated by the extra drive. Every few minutes, he turned around and said, “If that outfit can’t get someone from Plattsburg to Des Moines, Iowa, I don’t know how they think they’re ever going to get anywhere in the war!” Fortunately, the trains in Kansas City operated on Sundays. Riley arrived at Fort Des Moines about seven o’clock Monday morning. The first two weeks were easy. Academics consisted mostly of military history, first aid, a course called “Why We Fight,” and a slew of classes on hygiene. Enlisted men cleaned the latrines and pulled KP duty; all the women trainees had to do was make their beds. The fort was an old cavalry base converted into the training center, and the women were housed in a Civil War–era stable transformed into a barracks, with 125 bunks side by side. Riley remembered, “They’d treated the horses very well, I guess, because it was a nice stable.” After two weeks, the men left and the trainees did everything, often reporting for KP duty at five in the morning and going to sleep at ten at night. Riley’s worst fear was having to clean a grease trap. Fortunately, she never did, because she was pretty sure if she’d had to, she would not have completed her training. Once she hauled dozens of frozen turkeys with feet and heads attached from a walk-in refrigerator before she cleaned it. When turkey was served the next day, she couldn’t eat it. After basic training, Riley stayed at Fort Des Moines and learned to drive a ton-and-a-half truck. To help the war effort, the Army had removed two of the four rear tires, which made the trucks unstable. Riley was terrified as she drove around town with a load of soldiers, sure she would tip over at any minute. Riley’s truck driving didn’t last long; a slot at Officer Candidate School opened. After being commissioned, she and several other women went to a new training center at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. The women anticipated donuts and coffee they heard the United Service Organizations (USO) was passing out at a stop in Tennessee. But USO volunteers, expecting male soldiers, refused to give the women donuts. The slight stung. Fort Oglethorpe was in disarray when Riley arrived. With no uniforms for the fifteen hundred newcomers who poured in each week, the post handed out men’s overcoats. Women who had traveled in high heels stumbled about in the ill-fitting coats. Male soldiers at Fort Oglethorpe didn’t hate the women’s presence; the men just hated being there because they wanted to be in combat. Riley explained, “They felt that they would have an awful hard time explaining to their grandchildren what grandpappy did in the war.” *** The women’s status as auxiliaries caused problems for the Army almost from the beginning. Commanders in Europe clamored for women, but because they lacked benefits and protections, the Army limited them to duty in North Africa, which was considered relatively safe. To allow women to serve in Europe, both the House and Senate introduced bills in January 1943 to make the women full Army members. Not long after the bills were introduced, rumors and innuendo about promiscuity began flying. One story had twenty-six women being sent home from North Africa for pregnancy. A few days later, the number jumped to ninety and then five hundred, an impossible number given that only 262 women had ever been sent to North Africa. Of the three women who had been sent home, two had medical issues. A third woman was married and traveled to North Africa before discovering she was pregnant. Investigators found that only a few dozen women out of tens of thousands became pregnant; most were at a WAAC training center in Daytona Beach, Florida. There was no evidence of rampant promiscuity, but the smear campaign continued. On June 9, 1943, everything blew up. John O’Donnell, a columnist with the New York Daily News, reported that “contraceptives and prophylactic equipment will be furnished to members of the WAACs, according to a super-secret agreement reached by the high-ranking officers of the War Department and…Hobby…” O’Donnell retracted his claim the next day, but the damage was done. The same day as the retraction, Secretary of War Stimson minced no words when he denounced O’Donnell’s “sinister rumors” as “absolutely and completely false.” Singing the praises of the sixty-five thousand women who had released men for front-line duties, the secretary said, “Anything which would interfere with [women’s] recruiting or destroy the reputation of this corps and, by so doing, interfere with increase in the combat strength of our Army, would be of value to [the] enemy.” Edith Nourse Rogers went a step further, suggesting that those who spread such rumors might be guilty of sedition. The flap over the allegations died down, and Congress got back to work on the bill to make women full Army members. With Stimson and other Army brass on their side, the bill sailed the rest of the way through Congress. On July 1, Roosevelt signed the bill to establish the Women’s Army Corps, or WAC. Rogers had won her long battle. With the establishment of the WAC, for the first time in U.S. history, women who were not nurses served in the military as full equals to their male counterparts regarding protections, pay, and benefits. The women had not received full equality in other areas, though. They were still restricted largely to administrative specialties, and when the war ended, they would all be dismissed, even if they still desired to serve. But at the time, everyone was happy. Current Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps members had sixty days to reenlist in the WAC. Only about three-quarters of the enlisted women did, although it’s not clear how much attrition was related to the vicious rumors. Most women officers moved to the WAC. Emma Riley and other third officers became second lieutenants; Oveta Culp Hobby was elevated to full colonel. The WAC were here to stay, at least for the duration of the war. *** My great-aunt Florence Eighmy was one of the women who joined the WAC and trained at Fort Oglethorpe. Florence enlisted not so much out of patriotism but because she missed her husband, Bob, who was in the Army in Europe. She figured she could ask to be stationed somewhere in Europe, and the couple could meet up on leave. Born in 1921, Florence had few options after high school. She had good grades and longed to be a nurse, but there was no money for college. Instead, she did some modeling and worked as an accountant in a furniture store. In 1943, Florence met a handsome young soldier at a local hangout in Portage, Wisconsin. Bob Eighmy was assigned to nearby Fort McCoy, awaiting orders to ship out to Europe. The pair hit it off and married four months later. Bob left shortly afterwards. Florence enlisted a few months later, on March 29, 1944. She sent Bob a letter telling him she had joined the WAC and left for basic training. She took a train from Chicago to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and then boarded a bus with other enlistees to Fort Oglethorpe, an alien place teeming with cockroaches and mosquitoes that Florence dubbed “the swamps.” Southern customs, culture, and food baffled her. She detested watermelon but developed a lifelong affinity for catfish. The camaraderie among the women and childhoods formed by the Depression helped the enlistees survive boot camp: smallpox and tetanus vaccinations, training in gas masks, and lots of marching and scrubbing floors. Music from local radio stations often filled the barracks, and the women danced whenever they could. In addition to learning the mechanics of being a good soldier, Florence soaked up knowledge about the world through the eyes of women from all over the U.S. During training, Florence discovered she had made a strategic error: married WAC members weren’t allowed to be stationed overseas. The Army assigned her to Romulus Army Airfield in Michigan as an instructor in an airplane simulator called a Link Trainer. Her job involved setting up the trainer for pilots to practice flying in the clouds using their instruments; she also ran equipment that recorded their performance. Florence loved telling the pilots, who all outranked her, what to do. Some of the pilots were women. They wore uniforms, but they were civilians. They were there because more than a year earlier, Jacqueline Cochran had won her battle to get women into the cockpits of military aircraft. *** Getting women into military aircraft had not been easy. And initially, Cochran was furious with how things had turned out. On September 10, 1942, the Army Air Forces announced the formation of the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, and Cochran wasn’t in charge. She thought her deal with Hap Arnold would ensure no decisions were made until she returned from her job in England. Instead of Cochran, twenty-eight-year-old Nancy Harkness Love’s photo was plastered all over newspapers to announce her as the new organization’s “commander.” Despite her youth, Love was an accomplished pilot with twelve hundred flying hours. She was rated to fly high-performance aircraft and seaplanes, experienced at flying on instruments, and had ferried military aircraft from factories to the Canadian border, where Atfero pilots picked them up. She was married to Major Robert Love, whose job in Washington, D.C., had introduced Nancy to those who eventually approved her organization. “Commander” was an honorary title; Love and the women under her were employed as civilians, a decision made to avoid waiting for Congress to pass another bill regarding military women. The women pilots would work for the Air Transport Command, which ferried aircraft from factories to Army airfields in both the U.S. and overseas. Initially, the women would ferry only small airplanes like those they piloted as civilians. There were no plans for them to ferry aircraft overseas. The women had to be between twenty-one and thirty-five, be high school graduates, hold a commercial pilot’s license with privileges to fly airplanes with more than two-hundred-horsepower engines, and have at least five hundred hours of flying time. Love wasted no time setting up shop. The same day as the announcement, she arrived at New Castle Army Air Base in Delaware to start training the first fifty women. Five women pilots showed up the same day to take ground tests for entry into the program. One of them, Cornelia Fort, had been a flight instructor in Hawaii and was airborne when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. While in the traffic pattern with a student, she almost collided with another airplane that invaded the pattern. She thought the intruder was a rogue pilot until she spotted the Japanese insignia. She took the controls from her student and landed. Cochran wasted no time either. Hap Arnold knew he had blown it, and he acted quickly to give the famed aviatrix what she wanted. On September 14, he installed her in another civilian position, the director of women’s flying training. She would oversee a second organization that focused on training women who had less than five hundred hours of flying time. Love’s women didn’t need much training. But there were only about three thousand women pilots in the U.S., and very few of them had more than five hundred hours. Cochran would select women from the larger pool of less-qualified women; they needed only two hundred hours, a requirement lowered in the future. Cochran’s women would receive one hundred hours of Army instruction and would fly for Love’s unit after they graduated. Cochran’s lower-time pilots needed sixteen weeks of training. The training was at Howard Hughes Airfield (now William P. Hobby Airport), near Houston, Texas. Her trainees were paid $150 per month, rising to $250 after they graduated. The first class in Houston began on Sunday, November 15, 1942. Arnold wasn’t happy with two separate women’s organizations; he only agreed to it for expediency. On August 5, 1943, he merged the two groups, creating the Women Airforce Service Pilots, abbreviated WASP. Jacqueline Cochran led the combined organization. The military had previously used a handful of women pilots as contractors to teach men how to fly small aircraft, but Cochran’s and Love’s organizations were the first time that women who worked for the government flew military aircraft. The formation of the WASP further cemented their status as military pilots. There was just one problem: the WASP were still government civilians. It was a step above being contractors, but the women were still not in the military. *** Women pilots didn’t care about the politics or the names of the women’s organizations. They just wanted to serve and fly. Ann Baumgartner was one of them. Her WASP service began in a way similar to other women, but she veered onto a unique path. Growing up in Plainfield, New Jersey, Baumgartner was a precocious child who took ballet and piano lessons, rode horses, paddled canoes, climbed mountains, and skipped two grades. Her father warned her that smart girls, especially those who liked science, would probably never get married, but Baumgartner ignored his admonitions. During her freshman year at Smith College, she chose zoology and chemistry courses over art and switched her major to pre-med. After graduating in 1939, Baumgartner traveled to Europe alone and later met up with her mother. Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1 interrupted the sightseeing. The next day, Baumgartner and her mother boarded a U.S.-bound refugee ship in England. After leaving port, a call went out for passengers to help paint the portholes black to reduce the ship’s visibility as they passed through now treacherous seas. Given the uncertain times, Baumgartner put medical school on hold. She landed a job animating medical movies and then conducted research on vitamins. One cloudy day in late 1940, she took a break and climbed to the roof of her office building, where she spotted the silhouette of an aircraft as it prowled across the silvery sky. She imagined doing nothing but piloting that airplane, looking at the world stretching away from her. At that moment, she decided she would learn to fly. Baumgartner quickly earned her private pilot’s license and set her sights on gaining the two hundred hours she needed for a commercial pilot’s license. She and another pilot bought a little yellow Piper Cub and flew as much as they could. She also flew with the Civil Air Patrol, conducting patrols, assisting with rescue missions, and taking boys and girls for rides to interest them in aviation. The war soon crushed Baumgartner’s plans. By the summer of 1942, it was virtually impossible to fly a private airplane near the East Coast. But rumors swirled that the Army might start using women pilots. On September 1, 1942, Baumgartner read Eleanor Roosevelt’s “My Day” column, in which the first lady made the case for women pilots. Roosevelt railed against the establishment: “We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.” Nine days later, Roosevelt got her wish. Baumgartner was one of twenty-five thousand women who applied for Jacqueline Cochran’s training program. After an interview at Cochran’s Manhattan apartment, Baumgartner received the best Christmas present ever: orders to report to Houston in January for Army flight training. The bleak facility that greeted Baumgartner in Houston disappointed. Instead of the rows of shiny military training aircraft with a nearby chow hall and barracks she had imagined, she found dilapidated civilian airplanes and a ramshackle hangar. The trainees stayed in a hotel, two women to a room. Early training was a slog. The male instructors hated the women. But the women found salvation in Lieutenant Alfred Fleischman, a supply officer on the airfield. He led them through calisthenics, taught them how to march, and turned them into a proud team. Then, finally, some real military trainers—PT-19s and BT-13s—arrived, the same planes the men learned to fly. New instructors with better attitudes arrived as well. A bout with the measles interrupted Baumgartner’s flying dreams for a few months. After she recovered, she joined another class. By now, the women had moved to Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, which was a real Army base, complete with barracks, a chow hall, and a small infirmary. On August 30, 1943, less than two weeks before graduation, disaster struck Baumgartner’s class. Two trainees, Margaret Seip and Helen Severson, along with their instructor, Calvin Atwood, departed on a night cross-country flight in a twin-engine training aircraft. Seip wasn’t scheduled for the evening flight; she had volunteered that morning to replace another pilot. Ten miles north of Big Spring, Texas, the trainer suffered a structural failure and crashed. All three pilots were killed. The accident lay bare one of the problems created for the WASP because they weren’t in the military. For civil servants, the government did not pay to return remains and belongings to families. Still in mourning, Baumgartner and her classmates took up a collection to send the women and their possessions home. Baumgartner and her remaining classmates graduated on September 11, 1943. Of the 127 women who began training, 85 graduated. Jacqueline Cochran awarded wings to each woman. The Big Spring Bombardier School Band provided the music. After graduation, the women scattered to bases across the U.S. Baumgartner and another WASP, Betty Greene, went to the tow-target squadron at Camp Davis, North Carolina to replace two women who had been killed in accidents. Baumgartner enjoyed the variety of flying. One day she might fly an A-24 dive bomber at ten thousand feet above the ground while trainees tracked her with radars. The next day she might bounce around at treetop level in a tiny L-5 liaison aircraft while men tracked her with artillery. She also towed cloth targets behind a B-34 bomber and flew radio-controlled drones. Although the men at Camp Davis did not welcome the women pilots, not all the men they encountered were hostile. One day, Baumgartner and several others landed in a formation of A-25 dive bombers at a Navy base on Manteo Island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks. The women taxied to the ramp, shut down their engines, and climbed out. The young linemen sent to greet them stopped dead when they realized the pilots were women. They shouted, “Girls! What can we do for you ladies?” The linemen confirmed the women had landed on the airfield’s short runway used to simulate an aircraft carrier. They proclaimed, “You can consider yourselves carrier pilots now!” After a few months at Camp Davis, Baumgartner and Betty Greene reported for temporary duty to the Army’s Aeromedical Lab at Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio, home to the Wright brothers who had flown the first airplane forty years earlier. Colonel Randy Lovelace, the lab director, wanted to test cold weather flight clothing and study the impacts of high altitude flying and g-forces on women. The women were also asked to design and test something more fundamental: a tube for women to relieve themselves on long flights. Baumgartner and Greene found the research fascinating. They wanted to transfer to Wright Field to fly the plethora of aircraft that littered the ramp: at least seven different types of fighter aircraft, along with bombers, cargo airplanes, and helicopters. Another bonus: Wright Field attracted aviation royalty. Orville Wright, dressed in his iconic coat and hat, often made the short drive across Dayton to talk “aviation” with the test pilots. The colonel in charge of the Flight Test Division was open to the idea of employing the WASP. Greene ultimately decided to stay at Camp Davis, but Baumgartner arrived back at Wright Field in March 1944. The male pilots greeted her warmly, with curiosity and interest. Just as I learned four decades later, with a few exceptions, men in the business of testing airplanes had much smaller egos than their counterparts who flew aircraft in daily operations. Over the next few months, Baumgartner became part of the team, although she kept her distance socially from the men and had a policy of not dating her fellow pilots. But some wives were suspicious. One day Baumgartner overheard a pilot on the phone say to his wife, “Oh, you don’t need to worry. She’s only interested in flying.” She wasn’t sure if that was a compliment, but she wasn’t concerned about her supposed lack of femininity. Baumgartner’s first test flight was of a device mounted on the tail of an airplane that would warn a pilot when another aircraft was nearby. Another pilot flew his fighter aircraft slowly while Baumgartner zoomed her dive bomber at his tail from all different angles. The flying sure beat towing a cloth target. On another mission, Baumgartner flew to an island in Lake Erie to test a new gunsight on a P-51. Her instructions were to aim for a target on the eastern tip of the island and make several high-speed passes while firing the gun. The pilot who briefed her added, “But first you’ll have to clear the fishermen out of the area. Just buzz them and shoot off the guns. They’ll get the message. They know they’re not supposed to be there.” Sure enough, there were fishermen. She did as she’d been told, wondering what the fishermen would have thought if they knew a woman was shooting over their heads. She was fairly sure she was the only WASP to fire a fighter’s guns during the war. One day, the women’s relief tube Baumgartner helped design arrived. It was a small bowl-shaped funnel that could be positioned inside her flight suit and accessed via a crotch zipper or buttons. She chose a dive bomber for the test and was taxiing out when she was called back to the ramp. The lineman told her to take up an enlisted man who needed flying time. Baumgartner took off and flew around, trying to figure out how she was going to do her test with a corporal in her rear cockpit. Using her rearview mirror, she decided he couldn’t see into her cockpit, so she unbuttoned her flight suit and attached the device’s long tube to the receptacle used by the men. She looked back at the mirror to see what the corporal was up to. He was looking outside, so Baumgartner placed the device inside her flight suit, careful not to rock the airplane. She managed to relieve herself and didn’t feel anything spill, so she figured it must have worked. She put the device away and buttoned up, with the corporal none the wiser. The device worked, but the Air Force didn’t adopt it. Eight decades later, military women who fly high-performance aircraft still have a tough time when nature calls. Baumgartner’s best flight was yet to come. Rumors abounded that there was a secret jet fighter being tested somewhere, and that one might be coming to Wright Field for evaluation. The rumors were true. The XP-59A, powered by two turbo-jet engines, had made its first flight under great secrecy on October 1, 1942, from Muroc Army Air Field, later named Edwards Air Force Base, in Southern California. After initial evaluations, the Army ordered thirteen pre-production aircraft and sent one to Wright Field. The new colonel in charge of fighter flight test announced who would fly the jet: “certain FFT pilots, and that includes the WASP, who will be the first woman to fly a jet aircraft.” The pilots all flew the jet on the same day: October 14, 1944. The first engine start was memorable: black smoke and red flames shot out the back of the airplane as each of the two engines ignited. The first engine start blew the project’s secrecy: everyone on the base could hear the undeniable screech of a jet. The flights were short; the jet only carried about thirty minutes of fuel. Finally, it was Baumgartner’s turn. At the end of the runway, she pushed up the throttles “to a high scream,” and the jet lumbered along, its underpowered first-generation engines struggling with every inch. Finally, she was airborne. With the engine noise behind her instead of up front, the jet was much quieter than a propeller aircraft. As she slid silently through the air, it struck Baumgartner that she was likely in the only jet flying in the United States that day. She certainly was the only woman flying a jet. She had time for just a few maneuvers before she headed back and landed. Given the secrecy of the aircraft, there were no crowds to greet her, just the other pilots. It would be another decade before a second U.S. woman—Jacqueline Cochran—flew a jet. The month that brought the exhilarating jet flight also brought devastating news. The WASP would be disbanded in two months, just before Christmas. Cochran had battled since the first days of her program to get the women military status. But she flatly rejected suggestions that the WASP be incorporated into the WAC; she even threatened to resign if that happened. She claimed that “women pilots were a very temperamental group, and the administration of the program should be in the hands of one who understood them and their peculiar problems—that is, another pilot.” Certainly not Oveta Culp Hobby. Even with support from Hap Arnold and others, the WASP had an uphill battle. The good news of lower-than-expected combat losses meant there was no shortage of male pilots. There was even a surplus, and men complained that women were stealing their jobs. On June 21, 1944, Congress voted against legislation to give the WASP military status. Women who had expected to enter a class on June 30 were sent home. Existing WASP continued flying, but Arnold realized the women were no longer needed. On October 1, 1944, he ordered Cochran to deactivate the WASP no later than December 20. Cochran had lost, but she didn’t want the women’s accomplishments to be forgotten. A month before the disbandment, she praised the WASP during remarks to the National Aviation Conference in Oklahoma City: “I have not the slightest doubt but that these WASPs could have gone, if that were necessary, into combat work, fearlessly and effectively, just as Russian women have done.” In her final report, dated June 1, 1945, Cochran wrote that 1,074 women had graduated from the WASP training, and 900 of them—83.6 percent—remained employed with the program at the time of deactivation. Of the 1,830 women inducted, 58.7 percent finished their training, a completion rate favorable with the men. Thirty-eight women died, either during training or during operational flying, a fatality rate also comparable to men. The women proved they could do a wide variety of flying, from ferrying aircraft and towing targets to instrument instruction and simulated strafing missions. They flew almost every type of aircraft in the Army inventory, from light trainers to the massive B-29 Superfortress bomber, along with fighter aircraft such as the P-51 Mustang. Cochran also recommended that congressional action be taken to provide veterans’ benefits to the WASP who finished the program in good standing. It would take Congress another three decades to act on that recommendation. *** At the end of the war, the services discharged about 90 percent of those serving. Women were supposed to be discharged within six months of the end of the war, but a few were held back for an orderly transition. Many people, especially military leadership, believed there was a long-term role for women. The National Security Act of 1947, passed on July 26, overhauled the structure of the armed services and intelligence organizations. The act merged the War Department and Navy Department to create the Department of Defense, with oversight of all the services. The act also spun off the Army Air Forces into a new service, the United States Air Force. Women were not mentioned. Congress debated the fate of women for nearly another year, even though a bevy of prominent military leadership—James V. Forrestal, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley, Chester W. Nimitz, Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz, Hoyt S. Vandenberg—testified in favor of keeping the women. Finally, on June 2, 1948, Congress passed Public Law 625, the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, which gave women permanent status in the military. However, Congress and the services did not want women serving in large numbers; they wanted a foundation to build on quickly during an emergency. Thus, the law was far from perfect from a woman’s perspective. The number of women was limited to 2 percent of the overall force, only one woman in each corps could be a full colonel, and, with the exception of the Air Force, women were promoted separately from the men, potentially reducing women’s promotion opportunities. But the part of the act having to do with combat would have the largest impact on the future of military women. Almost no one at the time seriously considered that women could be in combat. Quite the opposite: Congress wanted to make sure they stayed away from combat and insisted on writing that into the law. The Army, with the potential for wide-ranging circumstances and areas of operations, could not come up with an easy definition of combat, so they were excused from being included in the law, with the understanding that they would write policies to ensure women didn’t engage in combat. Things were simpler for the Air Force and Navy: just keep women out of cockpits and off ships. The law stated that women “may not be assigned to duty in aircraft while such aircraft are engaged in combat missions” nor “may they be assigned to duty on vessels of the Navy except hospital ships and naval transports.” The language would haunt women for the next five decades.Discussion Questions

From the author:1. Before you read this book, were you aware that women served in large numbers during World War II? Discuss the limitations placed on them during World War II and through the 1960s. What societal influences led to the gradual lifting of these limitations?

2. To cover 50 years of history, the book has many characters. Discuss your favorite characters. Were there any characters who surprised you, either positively or negatively? What did you think about the author including herself as a character?

3. The vast majority of the women who fought for change never benefited from the change because they were either not in the military or were too old by then. Why did they fight for change if there was no benefit to them? Would you be willing to fight for a cause if it didn’t benefit you personally? What other causes and movements today may fall into this category?

4. Were you surprised at the number of men who were supportive of women in the military gaining more rights and access to more career fields? Who were some of those men? Why did they support women when others were opposed? How did this conflict come to a head in the 1970s during testimony about admitting women to the military academies?

5. What were some of the unintended consequences of the vagueness of the combat exclusion laws when women began serving in larger numbers in the 1970s and 1980s, especially when women began flying as pilots, navigators, and other aircrew members? Discuss how the laws, in addition to being unfair to women, caused confusion among commanders and had the potential to reduce the effectiveness of a unit.

6. Do you think that the laws would have been repealed eventually even if the Persian Gulf War in 1990-1991 hadn’t occurred? Discuss some of the events of the 1980s and early 1990s that made people realize the combat exclusion laws weren’t working.

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 1 of 1 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more