BKMT READING GUIDES

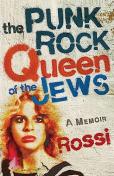

The Punk-Rock Queen of the Jews: A Memoir

by Rossi

Paperback : 336 pages

3 clubs reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

This is Rossi’s wild, queer coming-of-age story. Rossi was taught only to aspire to marry a nice Jewish boy and to be a good kosher Jewish girl. At sixteen she flowers into a rebellious punk-rock rule-breaker who runs away to seek adventure. Her freedom is cut short when her parents kidnap her and dump her with a Chasidic rabbi—a “cult buster” known for “reforming” wayward Jewish girls—in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

Rossi spends the next couple of years in a repressive, misogynistic culture straight out of the nineteenth century, forced to trade in her pink hair and Sex Pistols T-shirt for maxi skirts and long-sleeved blouses and endure not only bone-crunching boredom but also outright abuse and violence.

The Punk-Rock Queen of the Jews is filled with wonderfully rich characters, hilarious dialogue, and keen portraits of the secretive hothouse Orthodox world and the struggling New York City of the 1980s: dirty, on the edge, but fully vital and embracing.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

CHAPTER TWO ESCAPE FROM MESHUGA MOUNTAIN For as long as I could remember, I’d carried a secret. It had followed me like a shadow, except this shadow lived on the inside. I simply didn’t belong with the people who called them- selves my family.?As an adult, I viewed an old black-and-white film my father had made using a 1960s eight-millimeter movie camera. For years, it had sat in mothballs in the family attic, until my younger brother Mendel converted it to VHS. Nice of him, since he wasn’t in it. He wasn’t born until eleven months after it was taken. In the video, my sister Yaya was two-and-a-half years old. I was one. My mother Harriet and father Marty were both thirty-nine. They had been married ten years before having children. A few things about the film captivated me: seeing my mother still beautiful, before the extra hundred pounds and diabetes; seeing my parents in love, laughing and rejoicing in the simple pleasure of each other and their two babies. They were yet to embark upon three decades of sleeping in separate bedrooms. But mostly, I was fascinated by watching baby me standing in my crib, holding onto the side for balance with a look on my face that could only be read as, “Get me away from these crazy people!” Harriet wanted to raise her three 1960s children with values she’d internalized in the 1930s. She wanted her kinderlach to have as few goyish friends as possible, hoped that her daughters would marry Jewish doctors or lawyers and that her son would become the doctor or lawyer other mothers wanted their daughters to marry. Her children were expected to provide as many Jewish grandchildren as possible. Harriet might accept small deviations from her plan, but she drew the line at even the hint of intermarriage. She was convinced that the Messiah might one day sprout from one of her children and had no intention of allowing the line to be poisoned with Christian blood. The moment we could understand English, she taught us a bedtime prayer, drumming it into us like an army sergeant. No one was permitted to go to sleep without reciting it: “I pledge allegiance to the Torah, and to the Jewish people. I promise to live a good Jewish life and marry a nice Jewish boy” (or, in Mendel’s case, “girl”). One night when I was six, after I’d recited my prayer, I closed my eyes and tried imagining what the Jewish boy I was expected to marry might look like. Try as I might, I couldn’t conjure his image. After months of fruitlessly smothering my face in my pillow and searching for my imaginary spouse, the image of Wonder Woman from one of my tattered comic books appeared. I had a sense that there was something wrong with this. Still, no matter how hard I tried replacing her, every night Wonder Woman appeared in place of my future Jewish husband. A few months after WW’s initial appearance, I tried run- ning away from home for the first time. It was while our family was summering in Florida—“cheaper then,” Mom had said. I collected all the pears that had fallen from a tree outside our bungalow and filled up a pillowcase with them. While my parents were out trying to find kosher food in the Florida Panhandle, I dragged the pillowcase out of the yard, down the street, and fifteen blocks to the highway, intent on selling the pears. A few concerned citizens pulled over. Before long, I’d sold all the pears, which, besides being half-rotten to begin with, had been dragged fifteen blocks by a six-year-old. “What are you raising money for?” an elderly lady asked in a deep Southern accent. “I’s running away from home!” I answered, mimicking her drawl. I walked back to my family with an empty pillowcase, five dollars richer and proud that I was a little bit closer to striking out on my own. My second escape attempt was the raft. I have a vague recollection of my dad as a fun-loving guy in a faded white T-shirt wrestling my sister, brother, and me on the living room floor in Bradley Beach, New Jersey. We were playing a game he’d invented called “Get ’em, Boys,” and I loved it. Dad played rough; I guess the Navy had neglected to teach him the fine art of taking it easy on children. Long after my sister and brother hobbled away, I was still playing. I would let Dad think he won, then dive in for one more wrestling move. I always lost—hey, I was six—but I’d like to think I gave him a rough go of it. Mom’s idea of a fun kid’s game began with calling us over to the couch to sit on her lap. The idea was to slide down one of her short, wide legs onto the carpeted living room floor. At forty-four, she already suffered from an array of illnesses I didn’t understand, but I did know there was something fragile about her. I would often forgo the sliding game out of fear of breaking her. Plus, to be perfectly honest, it was no “Get ’em Boys.” I was a budding tomboy, and it was my GI Joe dad, with his hammers and saws and Ford pickup, who suited my tastes. I didn’t want to play with dolls; I wanted to dig in the dirt. By the time I turned seven, a seismic shift was occurring inside me that it would take me decades to understand. Despite my best efforts to the contrary, I began looking like a girl. Seemingly overnight, Dad pulled away, uncomfortable with any physical contact with his daughter. Why had he suddenly put a wall between us? All I knew was, for reasons beyond my understanding, I had been abandoned. That feeling grew venomous, until the very sight of him made me angry. “Get ’em, Boys” was retired and a harsh division emerged, leaving my dad and brother on one side of the cavernous gender divide and my sister, mother, and me on the other. The problem was that my little brother, the youngest of us, wanted to remain on Mom’s side, while I wanted to dig in the dirt with Dad. My sister, with her growing collection of dolls and aspirations to become the next Miss America, was the only one of us who seemed fine with the whole arrangement. Mom loved to reminisce about her days as a teacher. She had skipped so many grades that she’d gotten her Master’s degree by the time she was twenty and immediately entered the workforce. She put my father through law school on her teacher’s salary and was her hometown beauty queen. I would love to have known Harriet the beautiful career woman, but I never got to meet her. She suffered through eight miscarriages before she managed to carry a pregnancy to term. The moment she gave birth to Yaya, she abandoned teaching and proceeded to drown her boredom in food, coupon-collecting, and mothering her children like an overprotective Jewish hen on acid. The only Harriet I ever knew was a five-foot-tall, three-hundred- pound stay-at-home mom. She wasn’t exactly passive, but when it came to Marty, Harriet had a mantra: “Your father is right.” Mendel was issued a catcher’s mitt and baseball bat and sent off to Little League and any other sport he was willing to play. Marty encouraged him to look under the hood of the truck and taught him to top off the oil, among other manly things. Mendel was about as interested in these macho pursuits as I was in paper dolls. I did manage to talk my folks into buying me a GI Joe, but only by telling them that my sister’s Barbie needed a boyfriend. Maybe they figured out that sweet, fey Ken would never produce any grandchildren. One afternoon after school, I went into the backyard to play with our mangy half sheepdog–half beagle, Scout. In theory, he was white and fluffy, but since he lived in the yard, he mostly looked like dirt. At the far end of the yard, near the garage, I discovered a large pile of newly cut lumber. A gift from God! I began to hatch my plan. Every day after school I ran home and, using Dad’s hammer and hundreds of nails, worked on my masterpiece. My raft. It would be just like the ones I’d seen on TV. Huckleberry Finn had built one and gone off on great adventures, so why not me? Our house was six blocks from the ocean . . . surely I could create a raft sturdy enough to sail away from my family! Day by day, board by board, I laid the lumber out and nailed it together. I fashioned cross-pieces to hold the wood in place and made borders around the perimeter that I could hang on to if the wind picked up. Oh, it all made perfect sense to me. As soon as I was done, I would drag the massive structure (which probably weighed a hundred pounds) out of the yard, across busy Main Street, down six blocks, across another busy street, up the stairs to the beach, down the stairs onto the beach, across the sand, and into the ocean. Then I’d sail off to a distant land where nobody cared whether I was a boy or a girl. One afternoon, about two weeks into my project, I was upstairs in my bedroom working on the next part of my plan: how to steal enough food for my voyage. Peanut butter and fish sticks, I was thinking, trying to be practical about it. That’s when I heard the screaming. I don’t recall what that new lumber had been meant for, but I do know what it had not been meant for: a giant tangle of planks that may have looked like a raft to me but to Dad probably looked like a bad car wreck. I’d never heard my father make the kind of sounds that emerged as he tore apart my masterpiece, but they did seem somehow familiar. Then I realized: Godzilla movies. “AAAHHH!” came the cry accompanying the sound of splintering wood. “AAAHHH!” had come the screams of the Japanese people running from the fifty-foot lizard. I hurried down to the yard to find my beautiful raft in pieces. In 1971, parents saw nothing wrong with spanking their children, but Marty liked to up the ante by using his belt. The angry welts on my behind paled in comparison with the horror of seeing my creation destroyed. Right there was where Dad and I froze in time: he the dictator, and I the rebel leader. It would stay like that for decades.Discussion Questions

Discussion Topic Suggestions from the Author:Her identity as a rebellious punk rock rule-breaker, an adventure-seeker and a gay Hungarian Jewish feminist with a Yiddish-Jersey-Southern accent

Finding yourself amid restrictive cultural expectations

Her experience being forced to live under the care of a "cult busting" Chasidic

rabbi who aimed to “reform” wayward Jewish girls

Breaking out of a repressive, misogynistic culture in which she endured abuse

Facing the constant threat of assault, prejudice, homophobia, homelessness and

violence

Her decision to confront her past and make peace with it

Trying to survive her own personal crisis amid larger cultural crises (AIDS in NYC,

racial unrest, 9/11)

Advice to young people facing similar challenges and pressures to conform

Balancing her Jewish faith with her gay soul

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 1 of 1 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more