BKMT READING GUIDES

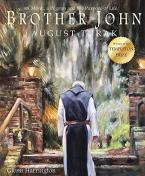

Brother John: A Monk, a Pilgrim and the Purpose of Life

by August Turak

Hardcover : 48 pages

0 club reading this now

0 members have read this book

Introduction

Recipient of the prestigious Templeton Prize, Brother John is the true story of a meaningful encounter between a man going through a mid-life crisis, and an umbrella-wielding Trappist monk. This magical encounter on Christmas Eve eventually leads the author, and us all, to the redemptive power of an authentically purposeful life. Uplifting, deeply moving, Brother John is dramatically brought to life by over twenty full color paintings by Glenn Harrington, a multiple award-winning artist. Brother John's moving story takes place at Christmastime, and its inspirational message and rich illustrations are sure to bring the reader back again and again throughout the year.

Editorial Review

No Editorial Review Currently AvailableExcerpt

CHAPTER 1 Brother John In any case, I feel I can personally guarantee that St. Thomas Aquinas loved God, because for the life of me I cannot help loving St. Thomas. -Flannery O'Connor Uncertainty as to life's purpose is much in vogue today. So, too, are the relativistic notions that would consign life's purpose to a matter of taste. The agony of life is uncertainty, and the rationalization is that uncertainty is certain. However, the plain truth is that, for all our anguish, we treasure uncertainty. Doubt forestalls action. The problem with life's purpose is that we know damn well what it is but are unwilling to face the changes in our lives that a commitment to self-transcendence, to being the best human being we could possibly be, would entail. It wearies us just thinking about it. So we rationalize that it's all "relative," or that we're already doing enough and don't have time. Worst of all, we rationalize that those who do accept the challenges inherent in self-transcendence are uniquely gifted and specially graced. It was eight in the evening on Christmas Eve, and I was waiting for Mass to begin. This was my second Christmas retreat at Mepkin Abbey monastery and my second Christmas Eve Mass. Mepkin Abbey sits on 3,132 acres, shaded by towering mossy oaks running along the Cooper River, just outside Charleston, South Carolina. Once the estate of Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, it is now a sanctuary for thirty or so Trappist monks living a life of contemplative prayer according to the arduous Rule of St. Benedict. Already eighteen days into my retreat, I was finally getting used to getting up at three in the morning for the monastic service of Vigils. However, I also knew that, by the time this special evening Mass ended at 10:30, it would be well after our usual bedtime of eight o'clock. The church was hushed and dark, and two brothers began lighting the notched candles lining the walls, as Gregorian chant, sung by the hidden choir, wafted in from the chapel. This chapel, a favorite meditation spot for the monks, sits just off the main sanctuary. The magic of these pre-Mass rituals quickly had me feeling like I was floating just above my seat. Soon I was drifting back to my first service ever at Mepkin, when Brother Robert, catching me completely off guard, urgently whispered from his adjacent stall, "The chapel is open all night!" This man, a chapel denizen who sleeps barely three hours a night, was apparently so convinced that this was the answer to my most fervent prayer that all I could do was nod knowingly, as if to say, "Thank God!" The sound of the rain pelting down on the copper roof of the church on this cold December evening drew me from my reveries, and I noticed, with the trace of a smile, that I was nervous. I had calmly lectured to large audiences many times, yet I was, as usual, worried that I would somehow screw up the reading that Brother Stan had assigned me for Mass. But reading at Mepkin, especially at Christmas, is such an honor. I felt that my reading came off very well. Returning to my seat, I guess I was still excited, because, heedless of the breach of etiquette that speaking at Mass implied, I leaned over and asked Brother Boniface for his opinion. Brother Boniface is Mepkin's ninety-one-year-old statesman, barber, baker, and stand-up comic. He manages these responsibilities despite a painful arthritis of the spine that has left him doubled over and reduced his walk to an inching shuffle. Swiveling his head on his short, bent body in order to make eye contact, Boniface lightly touched my arm with his gnarled fingers and gently whispered through his German accent, "You could've been a little slower — and a little louder." After Mass, I noticed that the rain had stopped. I headed for the little Christmas party for monks and guests in the dining hall, or refectory. Mepkin is a Trappist, or Cistercian, monastery, and its official name, "The Order of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO)," is taken seriously. Casual talking is actively discouraged, and even the vegetarian meals are eaten in strict silence. Parties are decidedly rare — and not to be missed. The party was a fine affair, consisting of light conversation, mutual Christmas wishes, and various Boniface-baked cookies and cakes, along with apple cider. Mostly I just basked in the glow of congeniality that I had come to associate so well with Mepkin. I didn't stay long. It was almost midnight, and, after a long day of eight church services, packing eggs, mopping floors, feeding logs into the wood-burning furnace, and helping Father Guerric put up Christmas trees, I was asleep on my feet. I said my good-byes and headed for my room several hundred yards away. Halfway to the refectory door, I heard the resurgent rain banging on the roof, reminding me that I had forgotten to bring an umbrella. Opening the door, I was cursing and resigning myself to a miserable hike and a wet monastic guest habit for morning services, when something startled me and left me squinting into the night. As my eyes adjusted, I made out a dim figure standing under an umbrella, outlined by the rain and glowing in the light from the still-open door. It was Brother John in a thin monastic habit, his slouched sixty-year-old body ignoring the cold. "Brother John! What are you doing?" "I'm here to walk the people who forgot their umbrellas back to their rooms," he replied softly. Flicking on his flashlight, we wordlessly started off, sharing that single umbrella. For my part, I was so stunned by this timely offer that I couldn't speak. For in a monastery whose Cistercian motto is "prayer and work" and where there are no slackers, no one works harder than Brother John. He rises before three in the morning to make sure coffee is there for everyone, and is still working after most of his brethren have retired. Brother John is also what might be termed Mepkin's foreman. After morning Mass, the monks without regular positions line up in a room off the church for work assignments, and, with several thousand acres full of buildings, machinery, and a farm with 40,000 chickens, there is plenty to do. (As a daily fixture at the grading house, packing and stacking eggs thirty dozen to a box, I could easily skip this ritual. I never do. Perhaps it is the way Brother John lights up when I reach the front of the line, touches me ever so lightly on the shoulder, and whispers "grading house" that brings me back every morning. Perhaps it is the humility I feel when he thanks me, as if I were doing him a personal favor.) Yet Brother John keeps it all in his head. Replacing every lightbulb that flickers out somewhere is his responsibility. He supervises when possible and delegates where he can, but as he is always shorthanded, he is constantly jumping in himself at some critical spot. Throughout the monastery, the phones ring incessantly, with someone on the line asking, "Is John there?" or, "Have you seen John?" And through it all, his Irish good humor and gentleness never fades or even frays. Now, after just such a day, four hours after his usual bedtime, and forty years into his monastic hitch, here was Brother John eschewing Boniface's baking, a glass of cider, and a Christmas break in order to walk me back to my room under a shared umbrella. When we reached the church, I reassured him several times that I could cut through to my room on the other side, before he relented. But as I opened the door of the church, something made me turn, and I continued to watch his flashlight as he hurried back for another pilgrim until its glow faded into the night. When I reached my room, I guess I wasn't as sleepy as I thought. I sat on the edge of my bed in the dark for what I can say, with some conviction, was a very long time. Over the next week, I went about my daily routine at Mepkin as usual, but inside I was deeply troubled. I was obsessed with Brother John. On one hand, he represented everything I had ever longed for, and, on the other, all that I had ever feared. I'd read Christian mystics say that God is both terrible and fascinating, and, for me, Brother John had become both. Of course, my obsession had nothing to do with the fact that he was a monk and I was not. On the contrary, Brother John was fascinating precisely because I intuited that to live as he did, to have his quiet peace and effortless love, had nothing to do with being a monk and was available to us all. But Brother John was also terrible because he was a living, breathing witness to my own inadequacies. Like Alkibiades in Plato's Symposium, speaking of the effect Socrates had on him, I had only to picture Brother John under his umbrella to feel as if "life is not worth living the way I live it." I was terrified that if I ever did decide to follow the example of Brother John, I would either fail completely or, at best, be faced with a life of unremitting effort without Brother John's obvious compensations. I imagined dedicating my life to others, to self-transcendence, without ever finding that inner spark of eternity that so obviously made Brother John's life the easiest and most natural life I had ever known. Perhaps his peace and effortless love were not available to all, but only to some. Perhaps I just didn't have what it takes. Finally, I asked Father Christian if he could spare a few minutes. Father Christian is Mepkin's feisty, eighty-eight-year-old former abbot, and my irreplaceable spiritual director. Slight and lean, his head is shaven, and he wears a bushy, chest-length beard, which he never cuts. When I commented that his beard didn't seem to be getting any longer, he regretfully said that his beard had stopped growing and added, "While, in the popular mind, the final length of my beard depends on my longevity, in actuality, it depends on my genetics." Fluent in French and Latin and passable in Greek, he acquired PhDs in Philosophy, Theology, and Canon Law as a Franciscan before entering Mepkin. His learning, his direct yet gentle manner, and his obvious personal spirituality make him an exceptional spiritual director. And while he grouses once in a while about the bottomless demand for his direction, I've never known him to turn anyone away. I told Father Christian of my experience with Brother John, and I told him that it had left me in an unsettled state. I wanted to elaborate, but he interrupted me. "So you noticed, did you? Amazing how many people take something like that for granted in life. John's a saint, you know." Then, seeming to ignore my predicament, he launched into a story about a Presbyterian minister having a crisis of faith and leaving the ministry. The man was a friend of his, and Father Christian took his crisis so seriously that he actually left the monastery and traveled to his house in order to do what he could. The two men spent countless hours in fruitless theological debate. Finally dropping his voice, Father Christian looked the man steadily in the face and said, "Bob, is everything in your life all right?" The minister said everything was fine. But the minister's wife called Father Christian a few days later. She had overheard his question and her husband's answer, and she told Father Christian that the minister was having an affair and was leaving her, as well as his ministry. Father Christian fairly spat with disgust and said, "I was wasting my time. Bob's problem was that he couldn't take the contradiction between his preaching and his living. So God gets the boot. Remember this: all philosophical problems are at heart moral problems. It all comes down to how you intend to live your life." We sat silently for a few minutes, while Father Christian cooled off. Maybe he finally took pity on the guy, or maybe it was something he saw in my face, but when he spoke, the anger in his clear, blue eyes had been replaced by a gentle compassion. "You know, you can call it original sin; you can call it any darn thing you want to, for that matter, but, deep down inside, every one of us knows something's twisted. Acknowledging that fact, refusing to run away from it, and deciding to deal with it is the beginning of the only authentic life there is. All evil begins with a lie. The biggest evil comes from the biggest lies, and the biggest lies are the ones we tell ourselves. And we lie to ourselves because we're afraid to take ourselves on." Getting up from his chair, he went to a file cabinet in the corner of his office and took out a folded piece of paper. Turning, he handed it to me and said, "I know how you feel. You're wondering if you have what it takes. Well, God and you both have some work to do, but I'll say this for you: you're doing your best to look things square in the face." As he walked out the door, I opened the paper he had given me. There, neatly typed by his ancient manual typewriter on plain white paper, was my name in all caps, followed by these words from Pascal: You would not seek Me if you had not already found Me, and you would not have found Me if I had not first found you. On close inspection, so much of our indecisiveness concerning life's purpose is little more than a variation on the minister's so-called theological doubts. Ultimately, it is fear that holds us back, and we avoid this fear through rationalization. We are afraid that if we ever did commit to emulating the Brother Johns of the world, we would merely end up like the Presbyterian minister: pulled apart between the poles of how we are living and how we ought to live and unable to look away. We are afraid that if we ever did venture out, we would find ourselves with the worst of both worlds. On one hand, we would learn too much about life to return to our comfortable illusions, and, on the other, we would learn too much about ourselves to hope for success. However, in our fear, we forget the miraculous. This fear of the change we need to make in our lives reminds me of an old friend who, though in his thirties and married for some time, was constantly fighting with his wife over her desire to have a baby. Every time he thought of changing into a father, the walls closed in. Fatherhood, he thought, was nothing more than dirty diapers, stacks of bills, sleepless nights, and doting in-laws in every spare bed and couch. Fatherhood meant an end to spontaneous weekends and evenings with the guys. It also meant trading in his sports car for a minivan and a bigger life insurance policy. It was all so overwhelming. Then one day he gave in. He set his jaw and made the decision to transform himself from a man into a father. He took the chance that he would find himself with all the responsibility of fatherhood and with none of its compensations. Then, on another day, his wife handed him his newborn boy. Unexpectedly, an inner alchemy began, and something came over him from a direction he didn't know existed. He melted, and, magically, the baby gave birth to a father. He was so full of love for this child that he didn't know what to do with himself. While he once feared losing sleep, he began checking his baby so often that the baby lost sleep. He found himself full of boundless gratitude for his rebirth, regret for the fool he had been, and compassion for single friends who simply couldn't understand. He called it a miracle. Similarly, we must take a chance and act on faith. We must give in, make the commitment, and be willing to pay the price. We must commit to becoming one with that passive spark of divinity longing for actuality that Thornton Wilder in Our Town describes so well: Now there are some things we all know but we don't take'm out and look at'm very often. We all know that something is eternal ... everybody knows in their bones that something is eternal and that something has to do with human beings. All the greatest people ever lived have been telling us that for five thousand years and yet you'd be surprised how people are always losing hold of it. There's something way down deep that's eternal about every human being. We must commit to facing our doubts, limitations, and self-contradictions head-on, while holding onto this voice of eternity. This eternal voice is urging us to take a chance on an unknown outcome in much the same way that nature's voice urged my friend to take a chance on a new life. And we must fight distraction, futility, rationalization, and fatigue at every step.Discussion Questions

From the author:Does Brother John as a character speak to you in any meaningful way?

Can you relate to the author’s moral dilemma?

How does it apply to your own life?

Does the artwork in Brother John complement the story?

Does it create the “spiritual buzz” the artist intended?

The artist never shows Brother John’s complete face. This was intentional. Why do you think the artist did this? Is it effective?

Brother John was originally an essay submitted to a contest answering the question: What is the purpose of life? Did the essay answer this question for you? Why or why not?

Book Club Recommendations

Recommended to book clubs by 0 of 0 members.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more