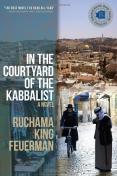

by Ruchama King Feuerman

Paperback- $12.36

2013 National Jewish Book Award Finalist

American Library Association Sophie Brody Medal Honor title 2015

An eczema-riddled Lower East ...

Overall rating:

How would you rate this book?

Member ratings

The prologue draws the reader in immediately by perfectly capturing the atmosphere of the kabbalist and his entreaters. In a dry and dusty courtyard, a rebbe and his wife show kindness to those in need: damaged people, people who are disfigured, emotionally disturbed, poverty stricken, any and all who come to seek their advice and food. They serve the needs of these sad misfits with no place else to go to seek counsel or solace. Somehow, their wise and common sense advice, delivered in the simplest of terms, calms and aids these suffering people.

Enter Isaac, a religious Jew, recently bereaved because of the loss of his mother. He has sold his haberdashery store and traveled to Israel. Instead of returning to the United States, he decides to stay and become the apprentice to Rebbe Yehudah, a man who offered caring, common sense advice with such sincerity that his solicitors believed him and often went away happy with their problems on the way to being resolved. Isaac suffers from severe eczema, psoriasis and unbelievable insecurity. His lack of confidence is his worst enemy and the cause of many of his problems.

Now enter Moustafa, a Muslim, born with a severe deformity. His head is turned to the side so he can never look completely forward. He is ridiculed and ostracized because of his deformity. Uneducated and a bit simple, he is a janitor on the Temple of the Mount, a holy place for Muslims and Jews, but a place where Jews are forbidden to pray because of its sacredness, and because the Muslims also forbid it. He learned Hebrew and English because of the kindness of woman who took him to weekly services when he was young. He is not devout in his faith, mostly because he does not pray in the mosque with the other men. He makes them uncomfortable, and they fear he brings the evil eye wherever he goes.

Moustafa and Isaac met quite by chance. Isaac was walking in an Arab area near the Temple Mount, and Moustafa, wondering what he was doing there, asked him if he was afraid to be there. Isaac, eyeing Moustafa’s pronged rubbish tool, asked why he should be afraid. They enter into a conversation, and when Isaac found out what Moustafa did, he called him a kohain. Moustafa was mystified. What was a kohein? Moustafa became a bit obsessed with the idea that he had this special significance and “therein lies the rub” and on the other side of the coin, the beauty of this story which seemed very much like a parable to me.

We have two men from totally different worlds, a Muslim and a Jew, who both believed strongly in their own religions, and they became friends of sorts. Both were outcasts in their own way. Both came from a background in which one parent cold and rigid, even cruel, while the other was the counterpoint. Both are searching for solace and love, both find it hard to describe the things that they want and need to find the answer to their hopes and dreams. Both vacillate, even when they finally decide what it is they want to do. Both are innately kind. Both are surprised when others are kind to them. They find they have things in common, their work, their words, their needs and their friendship transcends the hatred that exists between their cultures and homelands.

Because Moustafa was so grateful for the gifts, chicken soup and kind words that Isaac had bestowed upon him, when he visited him in the courtyard, he wanted to present him with a gift as well. What would be appropriate for a poor Muslim janitor to give to a poor religious Jew? Moustafa cleans up the area on the Mount, and as he sifts through the dirt, he finds discarded objects which he believes have no value other than to show his gratitude for Isaac’s kindness; they are after all bits of detritus being crushed and thrown away as rubbish. So he passed some of these odd objects, broken bits of pottery and a clay pomegranate, to Isaac, as a token of his appreciation, and Isaac is overwhelmed by his childlike generosity.

The seemingly innocuous discovery and gift of the ancient pomegranate will bring danger to both of these innocent men and expose a hypocritical pattern of abuse that is taking place on the grounds of the Holy Mount. The Muslims on the Temple Mount have been deliberately destroying antiquities to rewrite history, to erase the record of those that came before them so they can claim to have been first, so that they can claim the land and its history. The Jews in charge know this but do not want it to be discovered since it will cause massive controversy and demonstrations that would be dangerous for all in the region.

The misunderstandings arising from this antiquities discovery will jeopardize the safety of both men. When it is resolved, the reader will be left with a difficult message to ponder. Who was right? Was it Sheikh Tawil who wanted to willfully destroy the artifacts, the Rebbe Yehudah who wanted the wanton destruction of history brought to light so the true heritage could be preserved, the blustering Commander Shani who as the Israeli Intelligence Officer, consumed by his ideology and politics just wanted to maintain secrecy to prevent violence, Isaac or Moustafa who only wanted to appreciate the objects he found?

The character development was textured with many emotions and images. Tamar came across as a flamboyant girl on a motor cycle, but also as someone more serious, possibly suited to Isaac, despite their age difference. Shaindel Bracha, the Rebbetzin, came across grandmotherly, but also all-knowing and a strong influence on the courtyard. Politics and fanatic leaders would seem to be the villains in this story, not religion. The book, on the surface is an allegory, but it also exploits the reader’s mind with subtle reminders of the Israeli conflict, subtle hints about the fractured societies trying to live together, subtle hints about how they survive, often owing to odd compromises with one group or another in order to keep the peace. If only both sides could see the other side’s needs more clearly, without prejudice, so much might be achieved, and yet, in conclusion, one is left to wonder if this is really a possibility since so much is still misunderstood, so many are still blind to anything but their own needs and never see the true nature or needs of another.

It feels like such a tender story. The Yiddish expressions, conversations between characters and simple sayings and comforting remarks are examples of the beauty of Israel and its oft unjustly ridiculed religious society which is pitted not only against the secular but also the conflicting religious points of view. I believe that even non-Jews could be warmed by the sentiments expressed by this storyteller, by the simplicity of the love, devotion and loyalty exhibited by these two so different men, both a bit Job-like. Both men grew larger in the end, but did they achieve their dream? The reader will be left wondering if Isaac betrayed his friend or performed a miracle for him. Is the spiritual message of the book only achieved if one is Pollyanna?

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more