by M. Nghia Vo Christina; Vo

Paperback- $17.99

Click on the ORANGE Amazon Button for Book Description & Pricing Info

Overall rating:

How would you rate this book?

Member ratings

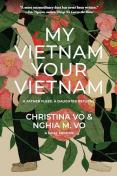

My Vietnam, Your Vietnam, A Father Flees. A Daughter Returns, Christina Vo and Nghia M. Vo,

authors of a dual memoir.

This book is an interesting perspective on the immigrant experience. One side is written by a person who fled war and persecution, who feels lucky to have enriched his life in his adopted country, America, and lucky for having achieved success; he feels accepted. The other, is written by his daughter, born in America, but who yearns for a connection to her father, taciturn by nature and background. She yearns to learn more about her heritage and her parents’ birth countries. She feels something is missing from her life. Because of his upbringing and the Vietnamese culture, her father never opens up to her to share his life completely, and that is a disappointment both to the daughter and the reader. When the book ended, I felt desperate for more. I wanted a more complete vision of what was accomplished by both of them, from their experiences. Did they have any great “aha” moments? It seemed, however, that like father, like daughter, for both sides of this memoir seemed to be written a bit clinically, and lacked emotional context.

With her need to discover who she was, Christina decided to visit Vietnam. She traveled first to Hanoi, a place her father rejected. She then went to Saigon and then back again to Hanoi. She liked different aspects of each city. Only in her very early twenties, her first job was an internship for no pay. However, by the time she felt ready to think about leaving Vietnam, and returning to America to live, it was almost a decade later. By that time, she had also worked for the United Nations, another job that did not seem to fulfill her needs. After approximately a total of 11 years, she returned to her birth country, the United States. Often, because she was searching for something she herself could not identify, she was not sure of what she needed or wanted and remained unsatisfied.

The short chapters pretty much alternate between the father and the daughter, but sometimes they seemed disconnected, with one having little to do with the other. Still, the description of the country and what it meant to both of them as a homeland, created beautiful images of the landscape. I would have liked a more comprehensive connection between their two experiences, and I thought that perhaps there would be a second book to follow, one that would elaborate more fully on their relationships and experiences in Vietnam. At the end, it seemed to me that where each was born, and what life gave them early on, informed most of their desires, ideas and experiences they sought.

Nghia Vo fled Saigon when the Communists invaded, but Christine was drawn to Hanoi and the Communist community because of its structure. Her father’s village, in Saigon, lacked the structure she craved, but offered the easygoing lifestyle and family connection that she missed. Unlike Nghia, who embraced whatever moment he was in, wanting desperately to be part of his adopted country, Christina consistently felt like an outsider, unable to embrace the experience fully.

The writing style of both father and daughter are engaging and inviting. I felt immediately welcomed into their world to discover about both their past and their present. Their descriptions were filled with the imagery of a country that is known for the beauty of its landscape and the gentleness of what is described as a peace-loving people, busy enjoying life at a leisurely pace before an enemy descended upon them. I had some difficulty with the language and names of the locales, as I had no idea how to pronounce them, but I tried not to let that distract me, so it did not prevent me from learning about their experiences or appreciating their necessary adjustments each time. I also discovered, from the narrative, what I had suspected would be revealed, that some believed that America had interfered, perhaps, in a place and conflict it did not belong. Was America responsible for a lot of the ensuing suffering or was the rescue of those who fled a bigger redeeming feature.

Immigration is tricky. If one is not willing to be part of the melting pot and insists on being a piece of the stew, can one fully integrate into their new country or will that person remain an outsider, eventually working to obstruct any effort to embrace them? In essence, from the start, America was a country completely populated by immigrants, so aren’t we all, in a sense, “other”, or “outside” the circle? I was left wondering if the immigrant experience was not what the immigrant made of it, or did it depend on the ability to blend into the society adopted. Physically and mentally, there is great variation. Lifestyle and living conditions vary as well. Is it possible to be really happy if you simply create a small version of your past life in your new one, or are you better off becoming a new person in your new life? Regardless of the choice, immigrants face a challenging future and their children sometimes face an unknown background and cannot find a comfortable place for themselves where they feel a part of the world they have been thrust into by others.

Book Club HQ to over 90,000+ book clubs and ready to welcome yours.

Get free weekly updates on top club picks, book giveaways, author events and more